Columns

Despite global climate extremes, why is climate action so slow?

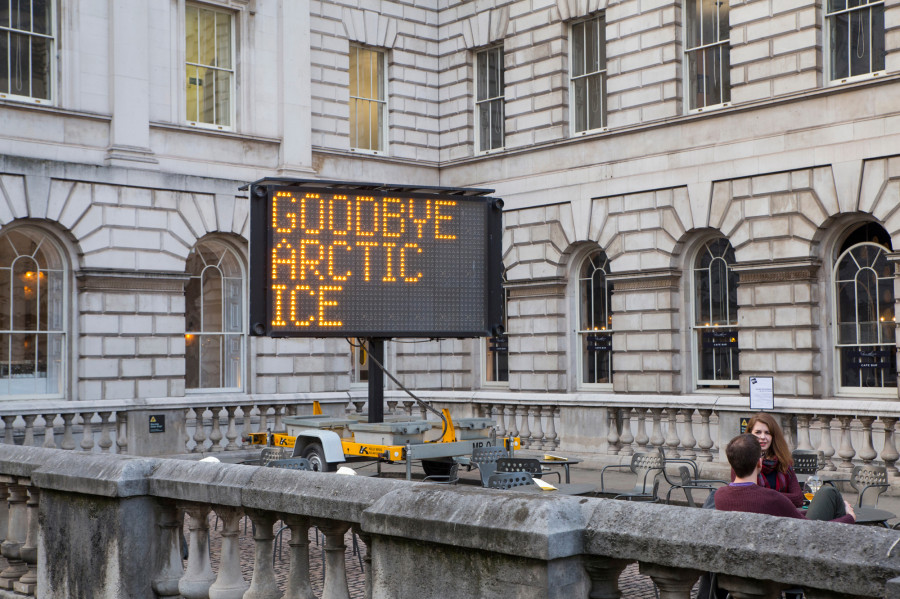

Denying, normalising or downplaying climate change impacts in our personal lives often leads to climate inaction.

Sneha Pandey

Over a hundred people have died and hundreds of thousands have been displaced in the first few weeks of the South Asian monsoon this year. These numbers were highest in Nepal, where the heaviest rainfall of the decade swept people, hillsides and highways away, leaving some of the world’s poorest to deal with unfathomable losses. Similar extreme conditions have been reported in other parts of South Asia, including India and Bangladesh, as well. With still a few more weeks of monsoon left, however, this disaster is far from over and casualties will continue to mount. Referring to these flood damages, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) sent out a message reminding people of the ‘urgent need to act on climate change’.

There was initial speculation that richer countries (of the Global North) would fare much better because, among other reasons, the weather was likely to get more pleasant as the climate warmed. However, this assumption is fast proving to be short-sighted, with temperatures surpassing 40 degrees Celsius in the region. This July—the month shaping out to be the hottest in Earth’s recorded history—heatstroke has been responsible for the deaths of several dozens of people in the US and Canada. New temperature highs are also being set in France, Britain, Germany and other European nations. In fact, the UK is seeing a record number of drownings as people desperately use bodies of water to stave off the heat.

Other major economies aren't faring much better either. The Middle East is experiencing higher-than-normal temperatures in the 50s. Australia reported scorching temperatures in January this year—the hottest month in recorded history for them. Today, climate change has indiscriminately swept across the globe creating ‘hellish’ conditions for all.

As the mercury continues to rise, the environmental and human impacts of climate change will become much bigger than they currently are. However, once the temperature rises to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels—the upper limit that the Paris Agreement has famously identified—these impacts will become irreversible. Despite this understanding, however, the UN calculates that the current 2030 mitigation commitments are nowhere close to being enough. The fight against climate change has, surprisingly, not picked up the pace. Why?

Climate denialism

Modern civilisation was built on the back of fossil fuels. Therefore, today, much of the world’s economy, technology, infrastructure and lifestyle is complexly tied to the carbon-intensive Big Oil industry. However, modern innovation in green technology is beginning to make fossil fuel somewhat obsolete. To fight back, Big Oil lobbyists have infiltrated some of the biggest markets—like the USA and Australia—and effectively managed to turn climate change into a partisan issue. This has fueled climate denialists, which eventually led to President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement.

A 2019 survey conducted in 23 of the world’s biggest countries found that among developed economies, the US and Australia had the greatest percentage of people who doubted the legitimacy of climate change. In the US, for example, as much as 17 percent of the people agreed that ‘the idea of manmade global warming was a hoax that was invented to deceive people.’

Such climate-denying constituencies, that vote for candidates who promise to scrap environmental protection policies, obviously hinder climate progress. However, climate denialism by itself does not paint a complete picture. After all, for every climate denialist, the study shows that there are many more who concede that fossil fuel emissions are leading to a rapidly destabilising planet. What then is keeping countries (and their people) from pursuing stronger mitigation action?

Behaviour lag

Because the science behind the changing climate is so complex, there is no straightforward solution that can completely rectify this issue. Addressing climate change requires fundamental shifts of cemented human behaviour on many fronts—a feat that is hard to achieve. For this reason, climate change has been referred by experts as a ‘policy problem from hell’.

Low carbon technologies like alternative fuels and energy storage have existed for well over a decade. However, the policies and infrastructure of many nations, that were designed during the age of fossil fuels, are locked in. Any change is perceived as too costly for the economy. This happens despite evidence that once initial capital costs are met, greener technology often tend to be more cost-effective.

As climate change increases the frequency of extreme weather, recent research suggests that people may start perceiving these events as normal. This study, which analysed the tweets of two billion Americans, shows that after as little as two to eight years of repeated impact, people tended to see extreme events as a result of natural climate variation (and by extension, not a consequence of climate change).

Compounding this problem is the fact that the causation between one particular extreme event and climate change is rarely established. Because climate change causes environmental disruptions in so many different (often hidden and cascading) ways, tying any particular event to climate change requires extensive research and resources. These causal linkages are, therefore, rarely established, leaving room for people to question the role of climate change in any single extreme episode.

These tendencies to normalise or question the legitimacy of climate change impacts in our own lives and immediate environment often leads us to justify that the rapidly warming climate is not affecting us. It is often perceived as a threat to distant people from another generation, other socio-economic strata or geographic region. This rationalisation gives us plenty of mental space to postpone action—to not change lifestyle, consumption, footprint, or policies.

Consensus and cooperation

It is human nature to look for immediate benefits over long term ones. And this is exactly what we tend to do when it comes to climate change. We either deny that there is a crisis or rationalise that taking action is expensive or unnecessary because the impacts are so very far away.

However, it is becoming increasingly clear that climate change impacts are already on all our doorsteps. The climate emergency is a global collective problem—it can only be solved with every nation’s consensus and cooperation. It is, therefore, now time to put short term interests behind us and work towards the greater good.

22.3°C Kathmandu

22.3°C Kathmandu.jpg)