Arts

From nature to silence

Min Thapa’s work explores the tension between nature and human-made change through haunting imagery and symbolic details.

Aarya Chand

Min Thapa is a visual artist from Mugu. His paintings come from real experiences—his own and those of people in rural Nepal. Over the past two decades, he has used his art to discuss important issues like environmental change, migration, and the loss of traditional ways of living.

Thapa’s work is shaped by the rapid changes happening in Nepal, especially the movement of people from villages to cities. As more people leave their hometowns, farms are abandoned, land is sold, and communities break apart. His paintings reflect this, not just in terms of empty villages but also in the emotional toll on lives uprooted.

His body of work spans over a decade—from around 2011 to 2024—and reveals a clear progression and consistent themes. Each painting unfolds like a movement in a requiem, beginning with the tension of forced migration, through the brittle collusion of artifice and ecology, to the ruinous aftermath of failed stewardship.

The first painting, ‘Migration’, shows a group of elephants walking across a colourful land. The painting comprises many small dots in purple, blue, and pink tones. It looks peaceful at first, but when we look closer, we notice something is wrong. The elephants are surrounded by tree stumps and axes. Tulips grow strangely out of the axe blades. There’s also a cactus or axe-like tree figure in the background—an example of object personification in the artwork.

Each tiny dot, each accumulation of pigment, deepens the metaphor and brings to mind the pointillist tradition I studied in class–Georges Seurat (who pioneered pointillism, creating luminous scenes through countless dots of pure colour) and Vincent Van Gogh (whose expressive brushwork and colour often echoed pointillist influence). The result is immersive, almost disorienting, echoing concepts of ‘visual affect’. The painting broods with overstimulation.

Amid the chaos, a moment of hope emerges: one elephant reaches for a tulip on a blade, a fragile symbol of resilience. The colour palette deepens this tension, calming greens clash with anxious reds, soft blues with urgent yellows. A hazy sun—or moon—lingers at the edge, leaving time uncertain. Is it dusk or dawn? The painting hovers between loss and persistence in the age of human impact.

The second painting I noticed does not have a title. It is whimsical in style, and reveals grim gravity. Again, Thapa’s pointillist technique demands viewers move close and then step back.

It shows a forest that has already been cut down. Only stumps are left—flat, lifeless remains of trees. One of the stumps has a water tap attached to it. Nearby, there’s a large clay pot, but it’s empty. Above them hangs a single light bulb, shining down in an odd, almost eerie way.

The tap doesn’t belong on a tree stump. It feels out of place—something forced or unnatural. The hanging light bulb also feels strange, like it was taken from a room and dropped into the middle of a forest. This uncomfortable mix of objects creates a strange, uneasy feeling. The light bulb hanging in the open space also brings to mind Pablo Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, where a single bulb shines over a scene of pain and confusion.

In the background, two green, human-like shapes are visible. It’s hard to tell what they are—maybe people, maybe trees, or maybe something in between. They seem to be moving or blending into one another, like shadows that are caught in a struggle.

Nature here has not been transformed—it has been replaced. The tap has no water. The pot is empty. The forest is silent. This is a landscape patched together with tools that don’t work. A failed repair of nature with the wrong parts.

The next painting that caught my attention was—‘Melting Life I’ and ‘Melting Life II’. These two paintings show a world falling apart.

In ‘Melting Life I’, a large sunflower is placed in the middle. It should be a sign of life, but here it is drooping and dripping. Around it are gears and machine parts.

Floating among them are small sperm-like shapes, turning the scene from mechanical to biological. This makes the painting feel very uncomfortable. It seems like even the most basic parts of life and birth are now stuck in machines. The machines are not helping—they’re blocking, breaking, or freezing what should be growing.

The sunflower, icon of Van Gogh and optimistic vitality, is reduced to a liquefied shell. By embedding sperm‑forms among gear teeth, Thapa critiques technocratic control of reproduction and ecology.

The painting imagery reminded me of Donna Haraway’s ideas of the cyborg (a feminist scholar who explored the mix of humans, machines, and nature), but instead of hopeful hybridity, it shows destruction. Fertility is frozen.

‘Melting Life II’, continues the unease. We can see mountains melting like ice cream. Yaks, buffaloes, and cows, which are animals usually found in Nepal’s hills, also seem to melt and lose their shape. The painting shows that even strong things like mountains and animals are now becoming weak.

As a viewer I sensed not death, but disappearance. There is no bright hope in this painting. It’s cold, grey, and sad. The melting isn’t loud or fast—it’s slow and quiet, which makes it feel even worse. Also if you see it for too long, the dense fields can evoke trypophobic unease as these works refuse to comfort; they demand discomfort. These are not decorative pastels, but affective matrices.

Next is artwork titled ‘Power’, here we see how environmental destruction is turned into a display of technological control. Like in earlier works, the world is built from tiny pointillist dots. But here, dots in yellows, ochres, and desert tones come together to form human-like machines standing among tree stumps and axes.

These machines—made of bolts, with pincer heads—look part-human, part-robot. They may seem a bit silly at first, but they carry a quiet threat. They stand like statues of industry, rising above the remains of a destroyed forest. Behind them, axes planted in the ground like crosses suggest nature has been sacrificed.

‘Power’ shows a future beyond humans, told through an environmental lens. These machines are not just tools—they’re treated like gods. Human hierarchy now succumbs to the hierarchy of the machines. These machines are more than figures—they’re symbols of control in a world that cuts down its own lifeblood.

The painting’s horror is subtle but powerful. Nature—and society—has worshipped machines to its own downfall. This work challenges the idea that progress is always good. It unmasks power as imposition—authority built upon the silence of forests felled, ecosystems erased. These machines now rule over a lifeless empire. Yet their reign is hollow. Their dominion is the desert.

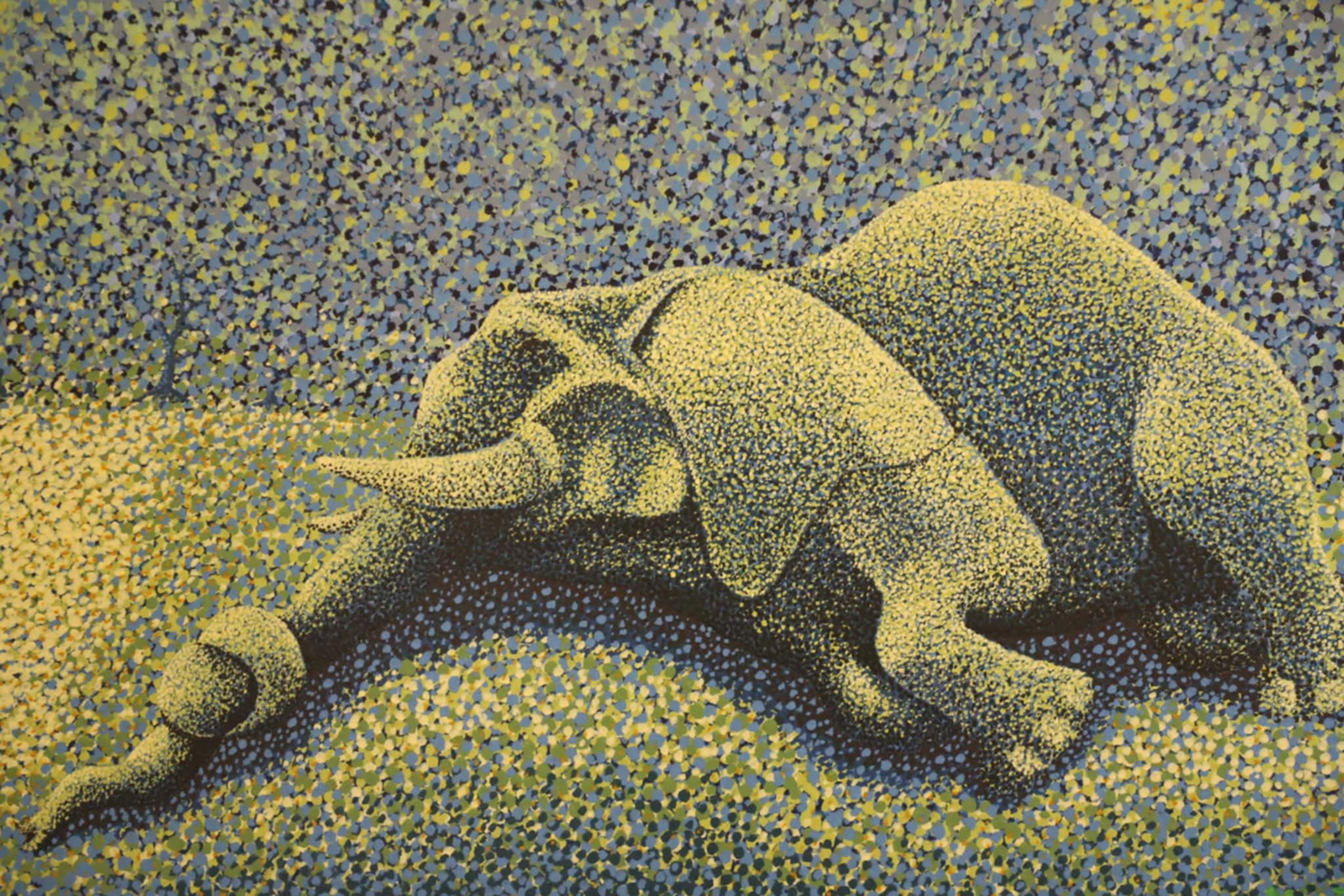

The final painting is ‘Homeless’, which is very simple, making it powerful. Here Thapa pares everything down. A single elephant lies on the ground in an open space. The background is made of dots to create atmosphere and texture; but only the elephant has gravity. There exist no trees, no horizon, no sky—only a void.

There is no pretense of motion. The form slumps and sags in static grief. The trunk is looped loosely—as if tethered. (Is it bound? Is it a noose?) The absence is total. The elephant is singular. It is alone.

This final image delivers the series morals. Not migration, not artifice, not melting—but absolute homelessness. It suggests that after nature and resistance have been annihilated, this is what remains.

When we look at all these paintings as one group, we see a clear message. Nature is being pushed away. Trees are cut down. Animals are forced to leave. Machines and tools take over. But in the end, these tools and machines don’t build anything real. They leave behind emptiness.

His series embodies pointillism, his expressive mode and affective technology. Each dot is a rupture. The works refuse the emotional distance of broad strokes and demand immersion—psychic, sensory, ecological.

That mourning at the centre is essential. This is art mourning nature—and implicitly, mourning ourselves. ‘Homeless’ doesn’t ask, “Who is homeless?” It answers: we are. Hence, this latest gallery does not console; it confronts. And in that facing, perhaps a sliver of emergence remains.

Etched By Progress

Where: Dalaila Art Space, Thamel

When: Till 30 June

Time: 11:00 am to 7:00 pm

Entry: Free

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=200&height=120)