Opinion

Leave no one behind

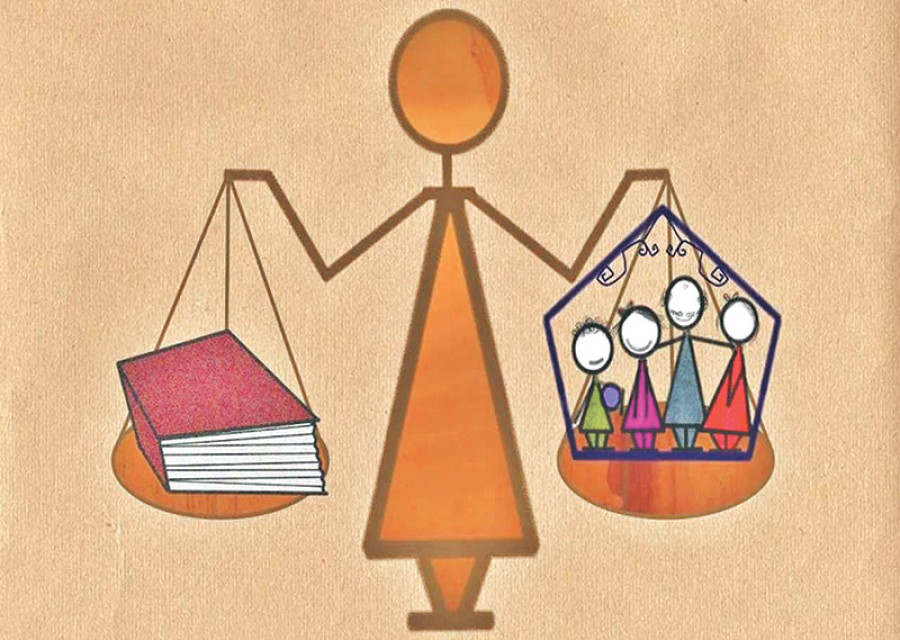

It is time to make the Nepali transitional justice model truly victim-centric and local

Ram Kumar Bhandari & Varsha Gyawali

The discourse on transitional justice is at a critical juncture today with the government likely to table a draft bill to amend the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act (Transitional Justice Act) in Parliament soon. While the new version of the act is being applauded for its efforts to adhere to the Supreme Court rulings of January 2014 and February 2015 and to conform to Nepal’s international legal obligations, several critical perspectives have emerged, particularly on how the amendments appear to be extremely lenient towards the perpetrators of human rights violations during the armed conflict and inadequate to address the victims’ key demands for truth, justice and reparation.

The Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs has pledged that the draft will be revised based on the victims’ recommendations. However, victim leaders and their associations are sceptical that this might be mere lip service as they have been given just about two weeks to respond to a complicated legal document. Since the victims were not involved in drafting the act and were not consulted during the formation of the commissions in the past, they are wary that their voices will be undermined once again.

They argue that transitional justice institutions have been regularly instrumentalised for political power play and the legitimation of dominant interests, mostly to protect the interests of the alleged perpetrators and beneficiaries of the armed conflict. Lately, the government and the powerful elite in Kathmandu have been pushing the agenda of ‘looking forward’ and ‘forgetting the past’ in their rhetorical speeches to perhaps distract everyone from finding the truth, making justice even less accessible to those seeking it.

Contextualising is key

At this juncture, what may be worthwhile is for the government to go beyond drawing experiences from other transitioning societies like Columbia, and instead acknowledge the messy social and political contexts within which violations occurred in Nepal’s armed conflict, and whose impact persists in the everyday injustices that Nepali people endure. These injustices were rooted not only in the experiences of the conflict but also in historical inequalities and systemic marginalisation. The particularities of the lived experiences of the victims, contextualised within their subaltern culture and local realities, should not be erased under the power of universal characterisation of justice, or in the name of taking inspiration from the West to mostly serve donor interest. If not addressed, lack of such contextual understanding may lead to disillusionment and tensions between the victims and the state, social polarisation among communities and the possibility of recurrence of violence in the future.

Victimhood also needs to be understood beyond the ‘victim-perpetrator’ binary because it tends to focus on the perpetrators’ accountability for rights violations and fails to articulate how people experience harm and their understanding of justice. Largely unaware and uninformed of the dominant narrative in Kathmandu, victims from the marginalised communities, with whom we interacted, make sense of justice in their everyday spaces and in their utmost urgent needs. They associate justice with their dignity, acceptance and respite from the social stigmatisation and exclusion they often face in the confines of their private domestic spaces and within the community they live. Therefore, the present government and federal Parliament must respect the victims’ demand for historical truth, their need for social justice and an authentic representation of the suffering of those violated.

But the reality in Nepal is that ‘law’ comes first before the victims. Rather than defining justice more broadly, the legal framework seems to privilege a narrow interpretation of justice that is perhaps more perpetrator-centric than victim-focused, and that is unable to attend to the varied needs of the victims and claims for justice that are not only related to the armed conflict but also claims for economic, social and cultural justice. The law more or less also ignores the responsibility of a society that is imbued with complex social relationships and power hierarchies that inform the experiences of victimisation. It also disregards the accountability of the governing institutions in the country, including the state security forces and political parties who have heavily politicised the transitional justice agenda and used it as a bargaining chip to pit one against the other to achieve their own vested interests.

Reflect deeper

As such, while everyone seems to be engaged in critical discussions on the draft act, there seems to be a need to reflect and develop a deeper understanding of how the global legal-centric transitional justice discourse is influencing our national narrative, so that the ongoing processes are able to deliver a form of justice that is meaningful to the conflict victims. One of the ways to achieve this is for government bodies to engage in genuine and wider consultation with the victims and their representatives, particularly with their umbrella network such as the Conflict Victims Common Platform in the Capital and beyond because more than 96 percent of the conflict victims live outside and do not have resources to come to Kathmandu. The relevant authorities and political parties must, therefore, prioritise nationwide consultations and community level discussions among those that the bill purports to serve.

The government and the political leadership may see the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act as just another bill to be passed by Parliament among many others, but for the thousands of victims and their families who have spent over a decade waiting for justice, this legal document can make a real difference in their lives and in how they secure justice in the future. There is a real opportunity before us to correct past flaws by recognising the victims’ right to truth, justice and reparation, and by incorporating their true voices in the draft act. Ensuring genuine representation and wider participation is likely to address the trust deficit between the state and the victims, where locally rooted victim groups and their movements across Nepal can feel a sense of ownership towards the ongoing transitional justice process.

It is time to make the Nepali transitional justice model truly victim-centric and local which recognises structural inequalities and socio-economic injustices endured by the victims, and encourages participatory approaches grounded in local cultures and context. This demands a strong political will to conclude what is probably the last unfinished business of the peace agreement for our country’s peaceful and equitable future.

Bhandari is a PhD researcher at NOVA Law School, New University of Lisbon, and Gyawali is a PhD researcher at the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations at Coventry University, UK

9.6°C Kathmandu

9.6°C Kathmandu