National

Amar Babu, or the terror of Durbar High School

The Bengali master’s punishments gave scars, but his lessons shaped generations of students in the 1930s and 1940s.

Prawash Gautam

“Did you bring your Taj Mahal Atlas?”

“I forgot, Sir.”

“Did you eat your lunch?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“How dare you! You don’t forget to eat your lunch, but you forget to bring atlas! fataha paji!” roared Amar Babu as his cane instantaneously rose to bear upon the boy.

Decades after leaving school, this is how Yagya Bikram Rana [later Brigadier General of Nepal Army], who attended Durbar High School in the 1930s-1940s, reminisced about his teacher Amar Babu in a memoir article “Durbar Schoolka Ti Dinharu” published in Nepali magazine in 2010.

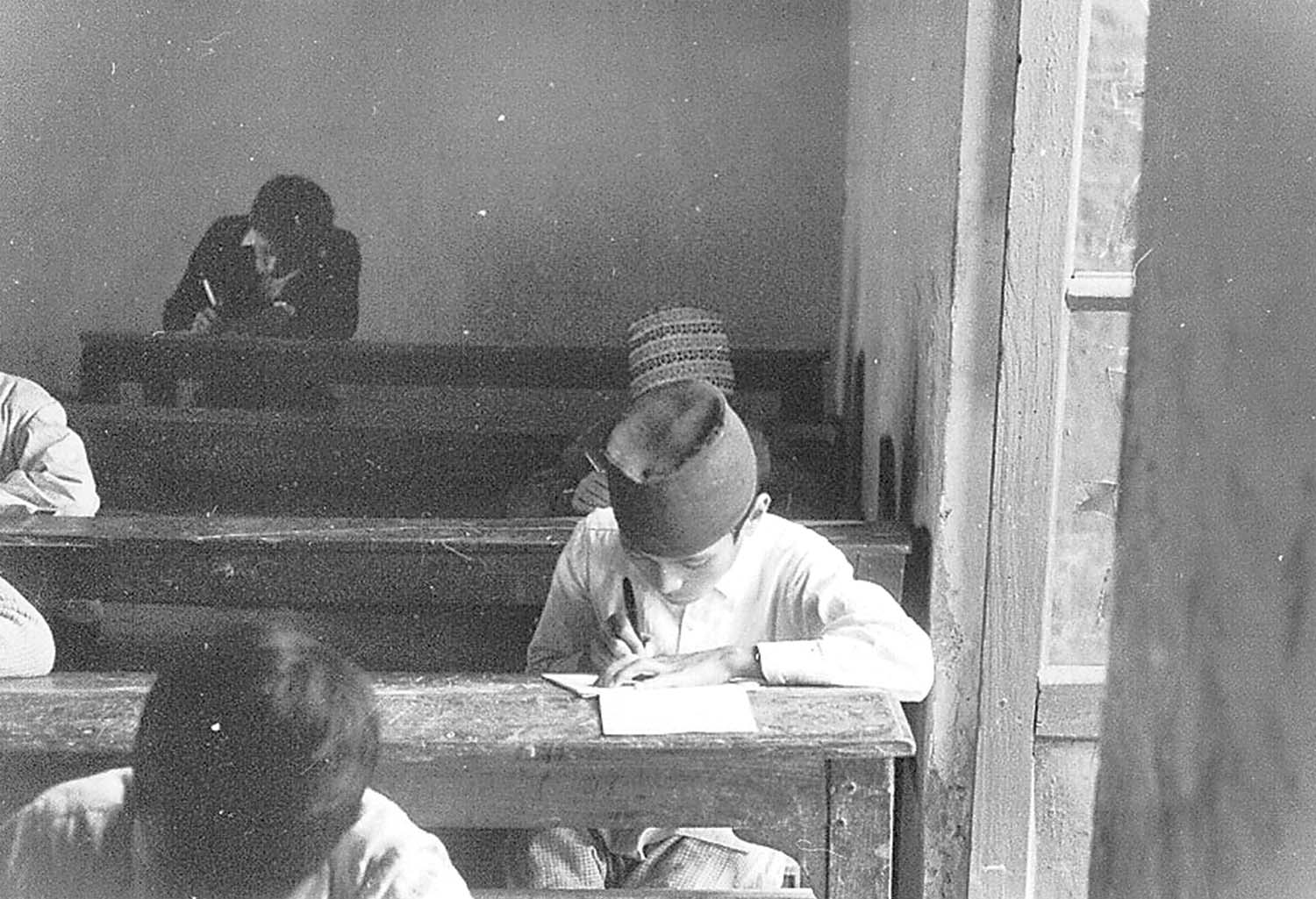

When Amar Babu, whose real name was Amarendranath Basu and who taught Mathematics and Geography, walked the corridors of Durbar School, the sharp clacks of his hard-soled leather shoes dispersed students and silenced classrooms. No boy who passed through the gates of Durbar School in the 1920s-1950s escaped his cane, or avoided having his ears twitched or hair plucked by Amar Babu’s unapologetic hands.

Rather, tormented by numerous varieties of ruthless punishments at his disposal, some would even leave the school. That is why writer Kamal Mani Dixit, another Durbar School student in the 1930s-1940s, wrote in his memoir Birseko Samjheko that “Amar Babu was ‘the terror’ of the school. There was no one who didn’t fear him. Even the most unruly students turned meek as mice before him.”

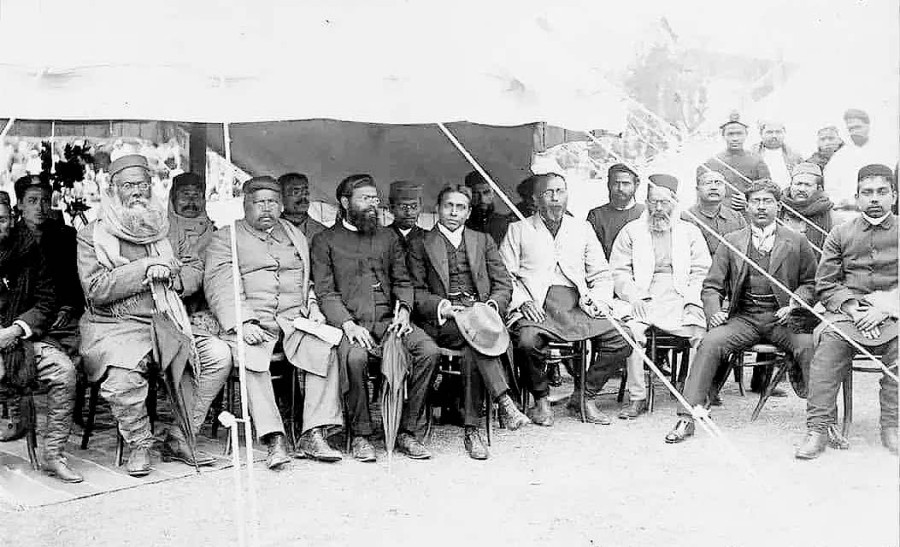

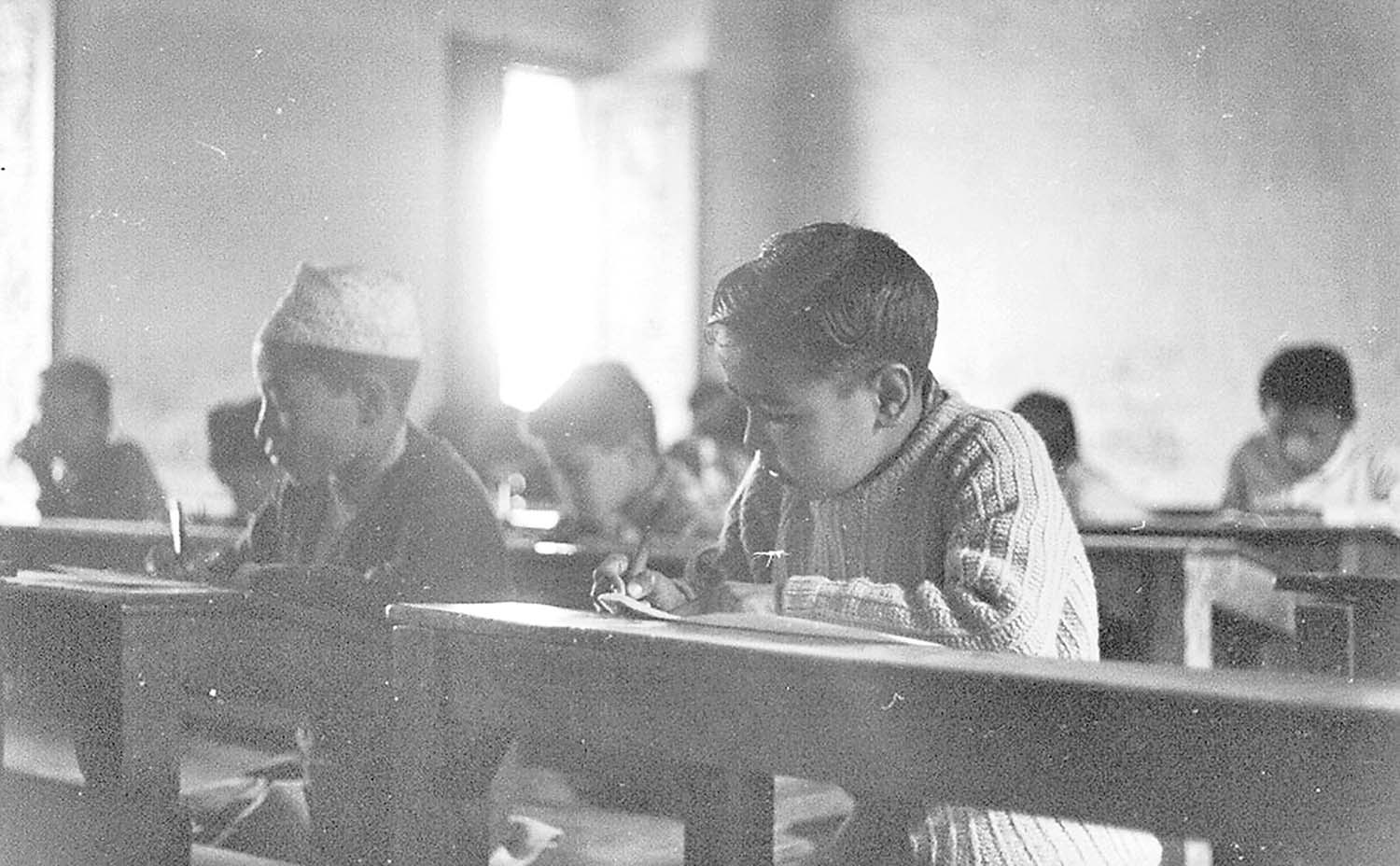

Durbar High School, the first Western-style school in Nepal, was established in 1854 by Jung Bahadur Rana, the founder of the Rana oligarchy, to educate the children of the Rana families. In the early 20th century, it was also opened to the children of the public. Right from its early years, the school recruited Bengali teachers to address the shortage of qualified tutors. The school’s alumni from the early twentieth century remember Bengali teachers for their idiosyncrasies, unique styles of teaching, and commonly, also for their beatings.

That was a time when corporal punishment in schools was not only acceptable but encouraged. As Ram Mani Acharya Dixit, a trusted employee of Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher, wrote in his diary, even the Prime Minister advised his older sons that they could “scold and beat [the younger brothers] to make them study.”

But some teachers took corporal punishment to an entirely new height. Like the fearsome Durbar School master, Garudadhwaja, whom dramatist Balkrishna Sama recounts in his memoir Mero Kavitako Aradhana as being “infamous for beating students” and “had beaten my father. Grandfather started tutoring him at home upon grandmother’s request to do so after looking at the bruises in his body.” By early 1930s, Garudadhwaja was long gone, but Amar Babu had already gained notoriety as the new master beater.

To start with, Amar Babu’s appearance itself was intimidating, reminiscent of, in the words of one student, Yamaduta – the messenger of Yama, the ruler of the netherworld.

“Black-complexioned and long sunken eyes, hollow cheeks, [adorning] English clothes [and] shaded cap, swinging a cane in his hands as he walked, that Bengali teacher looked like Yamaduta for real,” writes writer and artist Manuj Babu Mishra, who attended Durbar School in the 1940s-1950s, in his book Antar Taranga.

Amar Babu wasted no time in revealing his beater avatar to the students. When eight-year-old Tirtha Bahadur Shrestha enrolled at Durbar School in 1945/1946, Amar Babu was the first teacher he met. In his 2021 Kantipur article “Diwangat Hukkako Yaadma”, the noted ecologist and conservationist recalls how that first encounter left a lasting impression in his mind.

“Tumiro babule hookah khanchha ki khadaina? Nalile thokchha ki thokdaina,” Amar Babu asked Shrestha in his thick Bengali-mixed Nepali.

“Nalile pitnuhuncha mar’sab.”

“Ho, badmasi garyo bhane tumiro bubalai bhanidinchhu.”

According to Shrestha, now 87, Amar Babu entered the class with a large map of Nepal, framed by bamboo sticks 2-3 feet long. He raised those sticks up for the students to see.

“‘I’ll beat you with these if you don’t read,’ he said. Those sticks terrorised us,” Shrestha said.

Amar Babu’s beatings were accompanied by a barrage of abuses.

“Those abuses in Nepali that he spoke uninterruptedly – whoever taught him those – were astounding,” Dixit writes. “He’d say, ‘Komolmani Bahadur - kukurko lindo khane, bhoteko lindo khane moro hometask kyano korera ayenaa’.”

As he hurled abuses, Dixit recounts, Amar Babu’s hands grabbed the erring boy’s ear. Sometimes he picked both ears and lifted the boy off the ground before dramatically leaving him to drop. Many students had their ears wounded from Amar Babu’s ear pickings. Sometimes, he pulled the boy’s hair with both his hands, lifted him and dropped him down, causing wounds on his hands and legs.

Pulling the hair on the neck and sideburns were other punishments, which were reserved, Dixit writes, for the boys prancing long hair as long-haired boys infuriated Amar Babu.

Amar Babu’s punishments caused much more than just bruises and wounds. In his biography Living Martyrs, Tanka Prasad Acharya recollects some other varieties of Amar Babu’s punishments and how those eventually forced him to quit school. “I was weak in [Mathematics and Geography], so he used to beat me at every turn,” Acharya says. “[…] He had all sorts of ways of punishing us, from making us stand up on the bench for hours, whipping and thrashing us, down to compelling us to wear monkey caps and parade through the long veranda that stretched from one end of the school to the other, in front of all the ten classes. I could not bear such treatment, and finally one day after about a year I quit the school and began to take private tuition.”

The children of the Ranas got special treatment from Durbar School teachers. But Amar Babu’s cane spared none. Historian Pramod Shumsher Rana recalled being beaten by Amar Babu in a 2021 Edupatra.com article “Sikshaklai Mudki Hanepachi” by Dhaneshwar Upadhyaya. Yagya Bikram also remembered being caned by Amar Babu.

“One day, students of class 4 were making noise. Amar Babu was teaching in class 6. He sent a student to fetch me as I was the monitor of class 4. I didn’t go fearing that he’d beat me,” he writes. “Enraged, Amar Babu headed towards [class 4]. Meanwhile, gripped with fear, I was also going towards class 6. He found me on the way and instantly caned me three-four times. I fell down.”

In the early 1930s, historian Purushottam Shumsher Rana and his cousins were tutored by Amar Babu, who was hired by their guardians on the condition he wouldn’t physically punish them. Yet, Amar Babu had creative means to punish the offenders without raising a hand.

“He forced us to rub our noses on the table by making us press them against it and walk around,” Purushottam said.

Amar Babu’s unkind caning of Rana children belied his deep loyalty to the Rana regime. So, when the anti-Rana movement intensified in Kathmandu in the late 1940s, he saw, much to his dislike, Durbar School students join the protests.

Mishra, who supported the demonstrating students, found Amar Babu’s cane eagerly awaiting him.

“That was the time of the 1951 revolt. Since I was a student of a lower class, I wasn’t immediately able to comprehend the political rage of the students of Durbar High School, yet as a student artist I also used to contribute actively to their activities. I used to draw large posters, cartoons. I still get chills when I remember Amar Babu’s face and the beatings he [showered] on me for drawing anti-government sketches like those,” he writes in Antar-Taranga.

Behind Amar Babu’s back, though, students avenged his beatings.

“They say that in heaven all truth gets unraveled,” writes Dixit. “If Bengali Master Amar Babu is in heaven, he also must have known by now how much the students of Durbar School rebuked him then. […] The walls of the school building, toilets were filled with [mocking] praises for Amar Babu written with charcoal; some were entertaining, but others vulgar.”

In Antar-Taranga, Mishra remembers one such phrase that ran ‘Amar Babu Kale, Town Hall ko pale, Kukhurako Bhale’. Mishra himself sketched a cartoon of Amar Babu as revenge, earning him huge fame among fellow students.

But there came a day when even Amar Babu’s rage mellowed and students no longer secretly avenged but boldly retaliated. According to Yagya Bikram, Amar Babu’s beatings stopped after the then Director General of Public Education, Mrigendra Shumsher Rana, saw the red scars on Yagya Bikram’s back that had appeared as a result of Amar Babu’s caning and strongly ordered teachers to stop beating students. Meanwhile, Pramod Shumsher recalls that Amar Babu’s beatings ended after another student Pearl Jung Rana [later a known agriculturist] who was “a daring student… delivered a strong punch to Amar Babu” in retaliation.

A more elaborate account details that Amar Babu’s transformation came after the Rana regime ended in 1951.

“Amar Babu couldn’t accept Nepal becoming a democratic country,” Dixit writes. “Unlike earlier students, those after 1951 wouldn’t be content with merely writing abuses on the walls. Even Amar Babu began having ‘nervous breakdown’ once the school started having students who could scold back when he scolded them and didn’t even fear raising hands against him […] He immediately recognised me when I met and greeted him around 1954-55. But his language had transformed immensely. He apparently addressed everyone with hajur, sarkaar. When he saw me, he said, ‘Komolmani Sarkar Bahadur hojur… kosto hoiboksancha?’”

Another student, writer and political commentator Arbind Rimal, also felt that the political transformation had deeply affected Amar Babu.

“Around 1954/1954 […] I saw Amar Babu riding towards Jamal on an extremely worn-down cycle,” he writes in a 2021 article “Amarbabule Aankhabhari Anshu Gardai Dubai Hatkelale Jayjayko Aashirwad Diye” published in Nepalnamcha.com. “In a poignant voice filled with lamentation, he said, ‘Babu, you were angels [...] I was wicked, a sinner. Oh those curses I threw at you [boys], I beat you all so much. But you [boys] never said anything to me. Babu, today’s boys are very bad. A wicked boy that I know pushed me from behind when I was about to ride my cycle. Babu, that almost killed me. Oh Babu, the goodwill you all showed me!’”

Then, according to Rimal, with tearful eyes, Amar Babu raised his hands in blessing. This, he writes, was a gesture of a collective repentance of teachers like him for abusing students to express their loyalty to the rulers.

But was Amar Babu only a strict disciplinarian good only at beating?

Upendra Man Malla, one of Nepal’s foremost professors of Geography says that Amar Babu “was one of the capable teachers of Geography at Durbar High School” in Pioneers of Nepalese Geography by geographer Ram Kumar Pande.

Shrestha said that Amar Babu was adept at sketching Nepal’s map. On the blackboard, he drew two parallel lines six inches in length and cut them with a four inch long diagonal line, and on this framework sketched the diagonal map of Nepal, a process installed firmly in Shrestha’s mind to this day.

“Nepal’s map is diagonal, but this is something that most don’t seem to be aware of,” he said. “Many readers were surprised when I published an article with Nepal’s latitude showing Sagarmatha and Nepalgunj’s Dhamboji at about the same latitude. Amar Babu’s teaching us to draw the map has had a lifelong impact on me.”

Besides, Amar Babu was Durbar School’s headmaster in the last years of the Rana regime. He was also important in institutionalising geography in higher education in Nepal when the intermediate level was introduced at Tri-Chandra College in 1947, writes Pande in Pioneers of Nepalese Geography.

Amar Babu lived at the Bir Hospital quarters with his nurse sister. Later, he lived at the teachers’ quarters in Jamal with his wife and two daughters, according to 75-year-old Bharati Kumkum, a daughter of Nanigopal Sengupta, contemporary of Amar Babu and teacher of Maths and Physics at Tri-Chandra College.

In the 1950s, Amar Babu regularly visited renowned ayurvedic doctor of the time, Shivanath Rimal, at his residence in Tangal, recalls Rimal’s 90-year-old grandson Shankar Nath Rimal, pioneering architect and Amar Babu’s student. “I don't know what they talked about, but Amar Babu and grandfather sat on mats on the floor in his bedroom and talked for hours,” he says.

Another student, 92-year-old Khwaza Muhammad Moazzam Shah Raza Niyazi, whose father and younger brother both practiced traditional Unani medicine, says that Amar Babu had an aptitude in palmistry. It is, however, not known if his visits to and conversations with Rimal were connected to related fields of ayurveda and palmistry.

Amar Babu returned to Bengal after retirement, according to Kumkum. And although much of his life thereafter is not known, he apparently died a suffering death.

“Later I learnt that Amar Babu died after enduring very difficult times,” writes Dixit. “But this shouldn’t have happened. Because although he was harsh-mouthed, Amar Babu was an honest person.”

Today, like many Bengali teachers of Durbar School, Amar Babu rests in the fading memories of the last generation of his students. On the wall of the principal’s office of Durbar School hangs a wooden board listing the names of its headmasters. The ninth name on the list – Amarendranath Basu.

“Do you have any information about Amarendranath Basu? Any photo of him?” I asked the school’s principal Sharda Kumari Paudel.

“No. Nothing.”

“Any record at all about Bengali teachers?”

“All old documents were lost long before I came. I’ve been trying to locate them myself.”

Meanwhile, outside the principal’s office, students run carefree in the long dark corridor, calling and shouting at each other, unbeknownst to them the era when the sound of Amar Babu’s shoes emptied the corridors and silence descended in all of Durbar School.

9.72°C Kathmandu

9.72°C Kathmandu