Money

Nepal plunges into its first recession in six decades

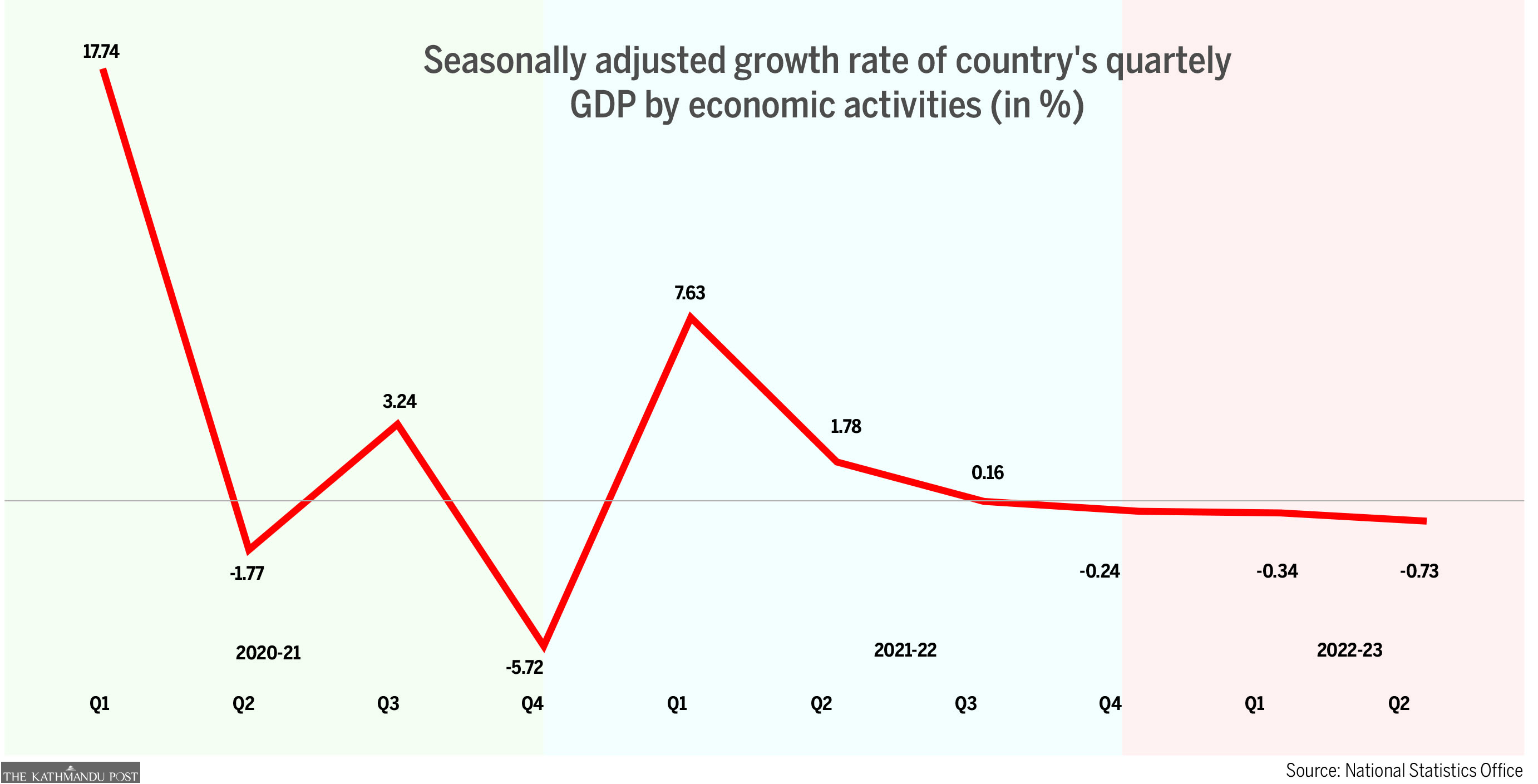

As per the Statistics Office, seasonally adjusted growth rate for the second quarter may drop by 0.73 percent.

Sangam Prasain

Nepal plunged into its first recession in six decades as economic output continued to be weighed down by inflation and political instability.

Economists warn that the country, which is aiming for middle-income status in the next three years, will have a hard time getting out of the slump as political uncertainty, corruption and market and climate vulnerability go deep.

As per the National Statistics Office, the seasonally adjusted growth rate or the gross domestic product (GDP) for the second quarter may drop by 0.73 percent.

The negative performance of the economy in the second quarter (mid-October 2022 to mid-January 2023) was triggered by slowed trade and a deceleration of the construction and mining sectors. This follows a nearly 0.34 percent drop in the first quarter (mid-July 2022 to mid-October 2022).

According to the government number cruncher, the economy in the first quarter of this fiscal year grew by 1.7 percent year-on-year.

But the first quarter growth rate of the current fiscal year is negative when compared with the fourth quarter growth rate of the last fiscal year. The growth rate in the fourth quarter of the last fiscal year was also negative by 0.24 percent.

Although there is no universally accepted definition of a recession, the widely agreed working definition is two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth.

Most economists agree with the definition provided by the National Bureau of Economic Research of the United States which says, “During a recession, a significant decline in economic activity spreads across the economy and can last from a few months to more than a year.”

Hem Raj Regmi, deputy chief statistician at the National Account Statistics Division, said, “The country was in recession until the first half of the current fiscal year. This is probably the first time since Nepal started keeping records in 1959. But the third quarter growth looks positive.”

Initially, the government had projected the Nepali economy to grow at 8 percent. The fiscal year started with a tussle between Nepal Rastra Bank Governor Maha Prasad Adhikari and then Finance Minister Janardan Sharma, highlighting the debate over Nepal’s economic crisis besides intensifying the political blame game.

Over the past months, the Post has been consistently reporting that Nepal’s economy is heading towards a crisis. In September, the Post wrote that the country’s foreign exchange reserves were coming under stress.

Then in December, a follow-up story revealed how Sharma was oblivious to the impending crisis and was making unsubstantiated statements that the country would achieve 7 percent growth, which economists said was impossible.

External vulnerability continued to put pressure on foreign currency reserves, but the authorities concerned turned a blind eye to it.

Halfway into the fiscal year, the statistics office downgraded the country’s growth rate to slightly above 4 percent in its mid-term budget review. The World Bank, International Monetary Fund and Asian Development Bank too lowered their growth projections for Nepal.

“We cannot deny the fact. It is difficult to achieve a growth rate of even 3 percent,” said Regmi. “The economy is severely under stress.”

He added that trade, exports and imports, the key sectors of the economy, plunged sharply. The agriculture sector did not perform well either.

In the second quarter, the mining and quarrying sector posted a negative growth rate of 18.51 percent compared to the first quarter growth which was 20.72 percent.

Wholesale and retail trade growth plunged by 4.33 percent. Transportation and storage saw a negative growth rate of 4.15 percent, and the growth rate of accommodation and food service activities dropped by 6.57 percent.

The growth of the construction sector was negative by 6.13 percent in the second quarter against a negative growth of 12.66 percent in the first quarter.

The construction sector, one of the country’s largest economic activities, has faced various problems. First, prices of building materials rose significantly.

Second, loans extended to the construction sector (including residential housing) declined due to a lack of loanable funds and high interest rates.

Third, the temporary closure of illegal crusher factories in January 2023 led to a shortage of construction materials such as sand and aggregates.

Rabi Singh, president of the Federation of Contractors' Associations of Nepal, says the government owes them Rs125 billion for various contracts. “The government is unable to pay the contractors due to lack of money.”

Economists say that the government is technically bankrupt.

The government has not made pension payments to 18,000 retired teachers of state-run schools for the month of Chaitra (mid-March to mid-April).

According to the Financial Comptroller General Office, the government had collected Rs693.75 billion in revenue as of April 20 this fiscal year. During the same period of the last fiscal year, revenue collection totalled Rs800.51 billion.

The Department of Customs said its revenue collection till mid-April of this fiscal year reached Rs285 billion, well below the target of Rs490 billion.

Speaking at the economic summit organised by the Kantipur Media Group last week, Nepali Congress leader Minendra Rijal said the government was in deficit to the tune of Rs400 billion.

“The government is in no condition to spend more than Rs220 billion under the capital expenditure heading in the current fiscal year,” Rijal said.

Economists say that the failure of the government to spend would further hurt economic activities, and could put the economy into complete disarray.

Last April, alarmed by the fast pace at which Nepal's foreign currency reserve was diminishing, the government imposed import restrictions besides ordering importers to maintain a 100 percent margin amount to open a letter of credit.

“After a few months of import restrictions, the results became visible. The prolonged foreign exchange controls by the government are the reason for the current economic slump,” said economist Keshav Acharya.

“Our country is now an import-driven economy, and restructuring imports means shooting oneself in the foot.”

The market went into the doldrums.

Stores are seeing a slowdown in discretionary spending by consumers, primarily because of inflationary pressures, reflecting how a slowing economy has dampened the market mood.

A credit crunch, real estate slowdown, tumbling stock market and rising unemployment have rattled the economy even as a new government was formed.

Nepalis are not buying cars, furniture, gold and clothes. Stores in Kathmandu’s major markets like New Road, Mahabauddha and Durbarmarg have launched sales offers, but buyers are still not showing up.

People are spending less at restaurants and purchasing less goods for their homes. They are cutting their budgets almost everywhere.

“Political instability has added to the economic woes,” said Acharya. “The government was least bothered to address the problems. The private sector, too, did not spend.”

Foreign direct investment too dropped to a new low. According to Nepal Rastra Bank, Nepal received foreign direct investment totalling Rs1.17 billion in the first eight months of the current fiscal year, a steep plunge from the Rs16.30 billion in the same period of the last fiscal year.

“This is because of political instability,” said economist Acharya.

Economists say that the consumption of goods and services, the key indicator of a healthy economy, has declined as a result of rising market prices. Daily consumable goods like rice, lentils, edible oil and vegetables have become more expensive, and the price rise is not seasonal.

Dairy traders raised the price of milk on their own. Transport entrepreneurs too jacked up the fares on their own. As did government-owned Nepal Oil Corporation.

According to Nepal Rastra Bank, the country’s central bank, the year-on-year consumer price inflation rose to 7.44 percent in mid-March compared to 7.14 percent a year ago.

Economists say that since inflation has risen from a higher base of 7.14 percent, Nepal is passing through hyperinflation, an extreme case of inflation.

“There is uncertainty everywhere due to political instability. We welcomed three prime ministers during my tenure of two years and four months,” Shekhar Golchha, immediate past president of the Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FNCCI), told a meeting recently.

The private sector's contribution to the country’s gross domestic product is 81 percent, and it accounts for 85 percent of the jobs.

A key indicator of an improved economy is the job market. But statistics show that Nepal has issued labour permits to 544,320 individuals to work abroad, and the country could see a record exodus of youths this fiscal year, excluding students and those going to India.

“The government failed to spend as did the private sector,” said Acharya. “There is no confidence in the market. The recession was imminent. We don’t know how long it will take to recover from the slump.”

The good news is that tourist arrivals and remittances are increasing.

8.4°C Kathmandu

8.4°C Kathmandu