Money

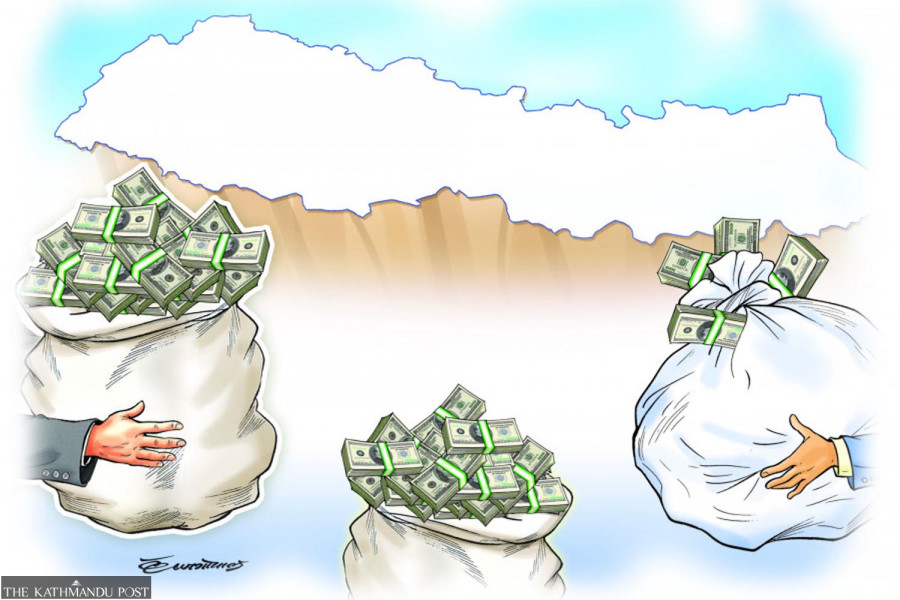

Debt concern grows as government borrowing doubles in three years

Newly enacted law on public debt management caps the external loans Nepal can take at a third of its gross domestic product.

Prithvi Man Shrestha

Nepal is nowhere close to defaulting on domestic and foreign debts but the ripples from the crises in Sri Lanka, Pakistan and other countries nearby are already being felt.

Sri Lanka was the first South Asian country to stop paying its foreign bondholders this year, burdened by unwieldy food and fuel costs that stoked protests and political chaos leading to the end of the Rajapaksa regime in the island nation.

The crisis in Sri Lanka dominated the discourse in Nepal’s political, academic and public circles, with many voicing concerns over the growing national debt.

Nepal’s total debt hit the Rs2 trillion-rupee mark for the first time last fiscal year, 2021-22. According to the Public Debt Management Office (PDMO), Nepal’s total debt reached Rs2.01 trillion, which is equivalent to 41.47 percent of Nepal’s gross domestic product (GDP).

The share of external debt is 21.14 percent of the GDP, according to its latest fourth quarterly report for the fiscal year 2021-22. The share of debt to the GDP was just 25.65 percent in the fiscal year 2015-16, according to the PDMO.

With rising debt, Nepali lawmakers agreed to cap the maximum external debt the country can receive from external creditors.

According to the newly enacted Public Debt Management Act, external debt is capped at one-third of the previous fiscal year’s GDP.

This is the first time Nepal sought to limit external debt though the public debt caps. Likewise, the maximum internal loans that the government can raise with the new law is Rs256 billion for the current fiscal year 2022-23.

“The cap imposed on external debt would discourage the government from borrowing recklessly,” said Hira Neupane, under secretary at the Public Debt Management Office. “Besides encouraging prudence in accepting external debt, it will also encourage the government to make timely debt payments so that it can borrow more.”

Though Nepal’s debt level is not alarming, the country’s total debt doubled to Rs2 trillion from just Rs1 trillion in the fiscal year 2018-19, according to PDMO.

With the share of external debt reaching an equivalent of 21.14 percent of the GDP, there is still room for Nepal to increase foreign debt acceptance by around 12 percent following the new law’s introduction. Nepal is not a highly indebted country, most debts have long payback periods, and they have been taken at concessional interest rates.

Nepal’s decision to limit external borrowing comes at a time a number of countries including well-publicised Sri Lanka are facing debt distress.

“When the Bill on Public Debt Management was under discussion at the Finance Committee of the House of Representatives, lawmakers also discussed the crisis emanating from Sri Lanka’s indebtedness,” said Surendra Aryal, secretary at the finance committee. “The committee decided to cap it to one third of the GDP so that the government would not be tempted to increase debt recklessly.”

By the first quarter of 2022, outstanding debt of Sri Lanka had reached 127 percent of the GDP, according to official data.

In May, Sri Lanka defaulted for the first time in history with the country facing a crunch of foreign currency due to reduced tourism income, curtailed revenue and rising import bills. The economic crisis resulted in the disgraceful departure of the Rajapakya family from power in Sri Lanka.

Likewise, Pakistan is also facing an economic crisis as it struggles to pay its enormous debt with its limited foreign exchange reserves. By December 2021, Pakistan’s debt to GDP ratio stood at 70.7 percent of the GDP, according to the World Bank.

In July, Bloomberg reported that a quarter-trillion dollar pile of distressed debt is threatening to drag the developing world into a historic cascade of defaults.

The number of emerging markets with sovereign debt that trades at distressed levels—yields that indicate investors believe default is a real possibility—has more than doubled in the past six months, according to data compiled from a Bloomberg index. Collectively, those 19 nations are home to more than 900 million people, and some — such as Sri Lanka and Lebanon — are already in default, according to the report. El Salvador, Ghana, Egypt, Tunisia and Pakistan are nations that Bloomberg Economics sees as vulnerable to default. Nepal is not on the list.

“For a country like Nepal, debt to GDP ratio of Nepal upto 50 percent is normal,” said Neupane, who is also the information officer at PDMO. “Average interest rate of our loans is around one percent, which is nominal.”

But Nepal has seen a rapid rise in debt in recent years after the country was forced to spend more on reconstruction after the 2015 earthquakes as well as during the Covid-19 crisis and the implementation of federalism.

“The country’s growing debt and the Sri Lankan crisis appears to have awoken our political class,” Bidyadhar Mallik, former minister and finance secretary. “That’s why they imposed a ceiling on external debt through legislative measures.”

He supports the idea of a debt-cap as Nepali leaders have a tendency of announcing populist programmes that create long-term liability for the state.

“There is also the risk of Nepali politicians being tempted to invest in vanity projects in the vein of the Sri Lankan politicians,” said Mallik, and a debt-cap will help with this as well.

However, a former finance secretary who wanted to remain anonymous, said that the imposition of the debt ceiling suggested that the government is not confident about its own fiscal discipline. “If the government is disciplined, there is no need to impose a cap on external debt. But the government here introduces oversized budgets promising to raise more debt,” he said.

Others advise finding alternatives to external debt. “The government should look to increase tax revenues, try to get grants from donors and maintain fiscal discipline,” said Neupane.

The government has also been more cautious in accepting loans from China, which is often accused by Western governments of leading vulnerable economies to ‘debt trap.’

Though the debt trap accusation is disputed, government officials have started requesting the Chinese side to offer its assistance in grants instead of loans for projects under the Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI).

During the visit of Chinese State Councillor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi in March, Nepali officials made it clear that Nepal prefers grants for the BRI projects.

As they discussed the implementation agreements on projects under the BRI, Nepal officials insisted that Nepal would prefer soft loans or concessional loans in case they had to get Chinese loans. “Recent events in Sri Lanka appear to have persuaded Nepal to reject commercial loans to implement BRI projects,” said Mallik.

23.88°C Kathmandu

23.88°C Kathmandu