Investigations

Maths teacher at Lalitpur Madhyamik Vidyalaya sexually abused young girls for decades

An investigation by the Post discovered a pattern of abusive behaviour by Bodha Raj ‘Basu’ Tripathee, based on interviews with at least seven female students who recounted molestation by Tripathee in the classroom.

Marissa Taylor & Pranaya SJB Rana

Rachana Dahal was in third grade when her maths teacher first put his hand up her skirt. Dahal, who was just nine years old, didn’t know how to react. The teacher, who was then in his 20s, would always find a way to sit next to her in the class, and would continue to molest her regularly for the next two years, she recalled in an interview.

Dahal, who is now 21, doesn’t remember the first time the teacher, Bodha Raj ‘Basu’ Tripathee, put his hands on her thighs. Nor does she remember the second. Or the third. What she does remember is how it made her feel.

“I couldn’t comprehend what was happening then. I didn’t know whether it was okay to be touched the way I was being touched—by a teacher in a classroom full of friends,” said Dahal.

Tripathee taught Dahal’s class at Lalitpur Madhyamik Vidyalaya in Lagankhel for two years, between 2005 and 2007, abusing her during the entirety of that timeframe. In class, his hands would often grab her thighs, sometimes massage them. One time, she said he went as far as to reach inside her underwear.

An investigation by The Kathmandu Post discovered a pattern of abusive behaviour by Tripathee across decades, based on interviews with at least seven female students from various years who described similar tactics of molestation in his maths class. Tripathee remains a teacher at the school, and despite numerous complaints against him, the school administration appears to have taken no punitive action.

In a phone conversation with the Post, Tripathee denied the allegations and said he was innocent.

“I am shocked,” he said. “I am a teacher and I could never be involved in these kinds of things.”

When presented with the testimonies of all the women who spoke to the Post, Tripathee categorically denied having done anything wrong. “I am innocent,” he said.

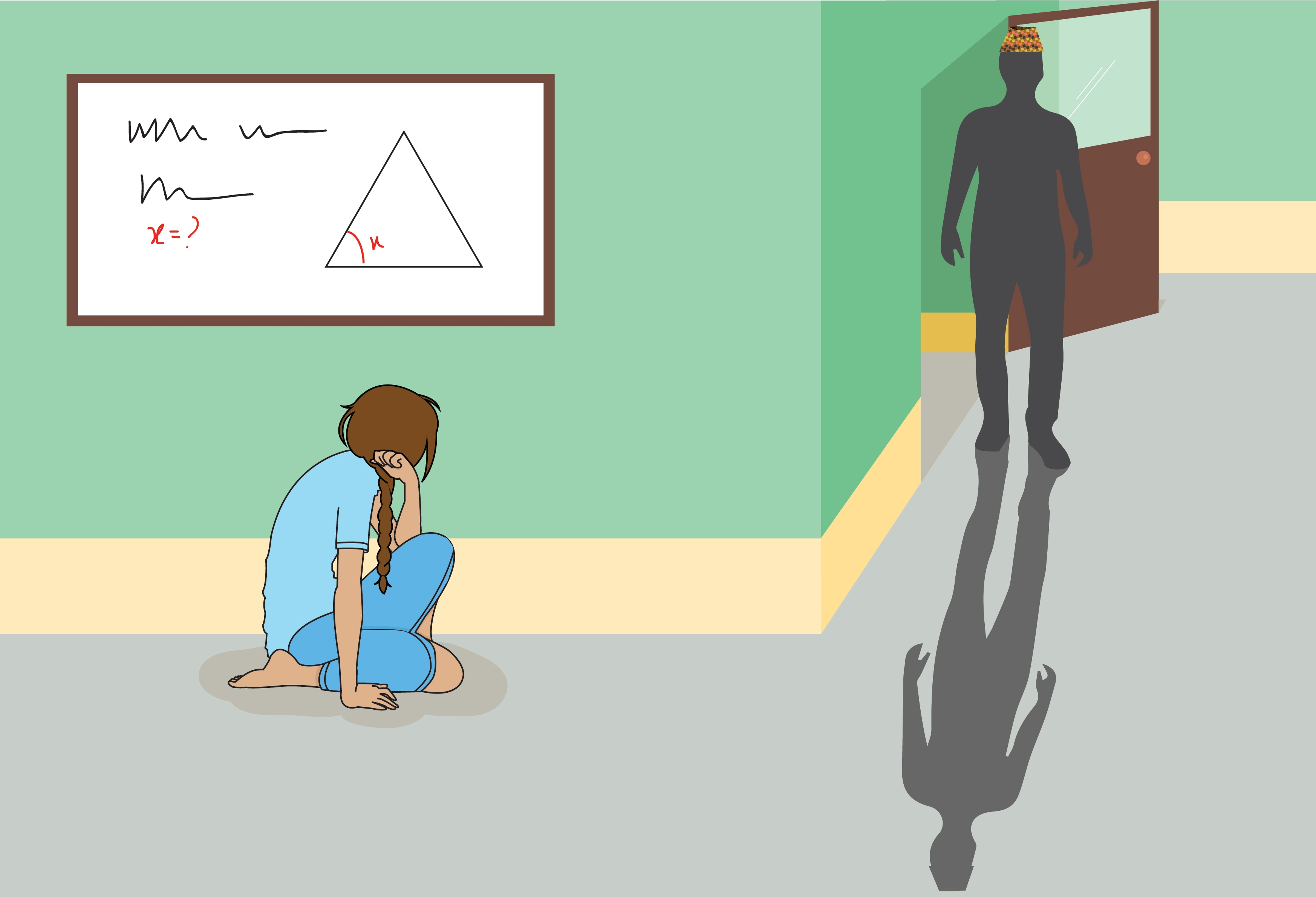

Female students at the Lalitpur Madhyamik Vidyalaya complained that they were sexually molested by their math teacher Bodha Raj ‘Basu’ Tripathee for decades

Female students at the Lalitpur Madhyamik Vidyalaya complained that they were sexually molested by their math teacher Bodha Raj ‘Basu’ Tripathee for decadesDahal wasn’t Tripathee’s only victim. Nisha Basnet, now 24, has similar experiences from her time at the school. When she was in fifth grade, she said Tripathee would reach under her tunic and put his hands on her bare thighs. Every week or so, Tripathee would pick a different girl to sit next to during classes.

At Lalitpur Madhyamik Vidyalaya, students would sit in groups of threes at a long desk—but because of Tripathee’s behaviour, the girls would always try to sit towards the wall so he couldn’t reach them, Basnet said in a phone interview from Australia, where she currently lives.

“It was so uncomfortable,” she said. “He would give us assignments and then ask us to sit on the edge of the bench so he could sit next to us and put his hands inside our tunics.”

Former students, many of them women, told the Post that Tripathee’s behaviour was an open secret at the school. “Everyone knew how he was,” said Anu Thapa, now 26. “We all tried to keep our distance from him.”

Although she was never directly molested by Tripathee, Thapa said that he would always attempt to touch her inappropriately. “He was always trying to touch our breasts and put his hands inside our shirts and skirts,” she said. “We were young and we didn’t dare to speak out against a teacher.”

Basnet, who was in Tripathee’s class from 2004 to 2006, said she remembers feeling violated and scared, but she did not understand what was happening. “I was scared of maths,” she said. “I was a good student in every other subject but I would always get bad grades in maths.”

Many of the women the Post spoke to shared similar experiences: they didn’t know what was happening, they couldn’t tell whether it was wrong and if they should speak out about it. But most of the women, who had just entered their teens at the time, said they felt uncomfortable and an inkling that whatever was happening was not right. Still, they said they couldn’t bring themselves to call Tripathee out directly on his behaviour.

Over the years, however, victims have attempted to register a formal complaint against Tripathee with the school administration. But little came of it.

“There used to be a green box at the school where we could leave our written complaints,” said one victim who asked to remain anonymous. She said she too was abused by Tripathee when she was in sixth grade about five years ago. “My parents sent me to the school because it had a reputation for focusing on academics, but I thought they had made a mistake,” she said.

The woman, who is now in her late teens and studying nursing, said a group of them lodged complaints numerous times—and repeatedly for two years—but no one in the school administration took any action. “Our seniors had told us that the complaints were read directly by the principal,” she said.

One of the women also said that a parent had directly confronted Tripathee about his behaviour. The Post attempted to reach out to parents but did not receive any response. Some of the parents asked the Post not to report the story and that they would find a way to resolve the issue internally.

However, all of the women the Post spoke to were insistent that their stories be told and said they hoped Tripathee is held publicly accountable for his actions.

Read: Tribhuvan University lecturer sexually harassed female students for years

***

Tripathee’s students remember him as an authoritative but friendly teacher. His authority didn’t just allow him to do as he pleased, it also secured him the silence from young girls he continued to molest for years.

“I don’t think he thinks what he did was wrong,” said Shubhasana Pradhan, 24, who was also molested by Tripathee. “What gives power to that thought is the fact that he was never punished for his crimes.”

Tripathee’s victims—all of them from third grade to sixth—were mostly abused in the presence of other students in the classroom. While none of the women the Post spoke to referred to any lasting harm, they admitted that the abuse had led to them performing poorly in school and feeling uncomfortable, insecure and afraid.

“When a child is molested chronically, they can develop a deep sense of self-blame, guilt and fear,” Dr Arun Raj Kunwar, a child psychiatrist, told the Post. “Because they do not understand what’s happening to them, some children tend to suppress their emotions, not talk about what’s happening to them, and, depending on the intensity of trauma, suffer through depression and even post-traumatic stress disorder.”

When it comes to cases of abuse and molestation, Nepali law is vague. Article 66 (3) of the former Children’s Act 1992 listed extensively what could be considered abuse, but lacked specific provisions when it came to abuse, molestation or harassment that happened in the past. However, the new Act Relating to Children, passed in 2018, has made incremental improvements.

“Recent amendments have been made to the Children’s Act that do look into child rights’ protection more strictly,” said Mohna Ansari, a commissioner at the National Human Rights Commission. “However, they are not nearly enough to protect children.”

Psychologists say that in many cases, children might not even understand or comprehend completely what constitutes abuse or molestation. It is only when they grow up and learn about sexual abuse that they recognise what happened to them as being inappropriate or criminal. This understanding can come years, even decades, after the fact.

When a crime is committed, the law provides a window of time when a victim can file a case against the perpetrator, called statutes of limitations. The statute of limitations for childhood abuse, according to Article 74 (2) of the recently enacted Act Relating to Children 2018, is a year after a person turns 18.

“While this provision is progressive, there are more progressive provisions in other countries such as the United Kingdom, where the limitation for filing a complaint by an adult for the violence/abuse experienced during childhood is not narrowly framed, like in case of Nepal,” said Tania Dhakhwa, chief of communications at the United Nations Children’s Fund.

However, the definition of child sexual abuse is narrowly defined and the Act Relating to Children does not include serious crimes such as rape. The one-year statute of limitations on rape cases, as defined by Article 229 of the 2018 Civil Code, still applies even in cases of child rape.

Read: Fed up by harassment, Nepali women are going online to share their #MeToo stories

***

The only solace the girls at Lalitpur Madhyamik Vidyalaya could get was in the support they found in each other. “I used to feel disgusted at myself, and angry at him,” said Trishna Acharya, who was abused by Tripathee multiple times when she was in third grade, from 2004 to 2005. “He was our teacher and we were scared. The only thing we could do was talk with each other, and get through with the class.”

Acharya, who now lives in Australia, said that when she was in eighth grade, some senior students had spoken about Tripathee’s behaviour with Geeta Sitaula, the current vice principal who was a sympathetic teacher then. But once again, nothing came of it.

“Everyone knew. The students, the principal, even many parents. But nobody did anything to stop it,” Dahal said.

When the Post reached out to Sitaula, the vice principal, she initially denied having any knowledge about complaints of sexual abuse. When told that former students had named her specifically as having been informed about Tripathee’s behaviour, Sitaula said she had only assumed the vice principal’s position two years ago and that some students might have spoken to her in her capacity as a teacher but she didn’t recall any details.

Sitaula said if the students had reached out to her directly about Tripathee, she would have taken action. She then asked the Post to rethink running the story and that they would resolve the issue internally by taking action against Tripathee.

Basnet, however, remains adamant that Tripathee needs to be punished. “Acts like these might not be so excessive but they promote abuse,” she said. “We were primary school kids who were helpless.”

Dahal, too, is firm on her belief that what Tripathee did was unconscionable.

“It is appalling that he is still a teacher at the school,” she said. “This has been going on for decades: seniors used to detest him and juniors are still complaining. This has to stop now.”

Read: Former Kathmandu mayor decries 'rape of men’s rights' after women accuse him of sexual harassment

Have you experienced sexual harassment at work or have a confidential tip you’d like to share? You can securely get in touch with The Kathmandu Post editors using our encrypted email account: [email protected].

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu