Editorial

Crime against children

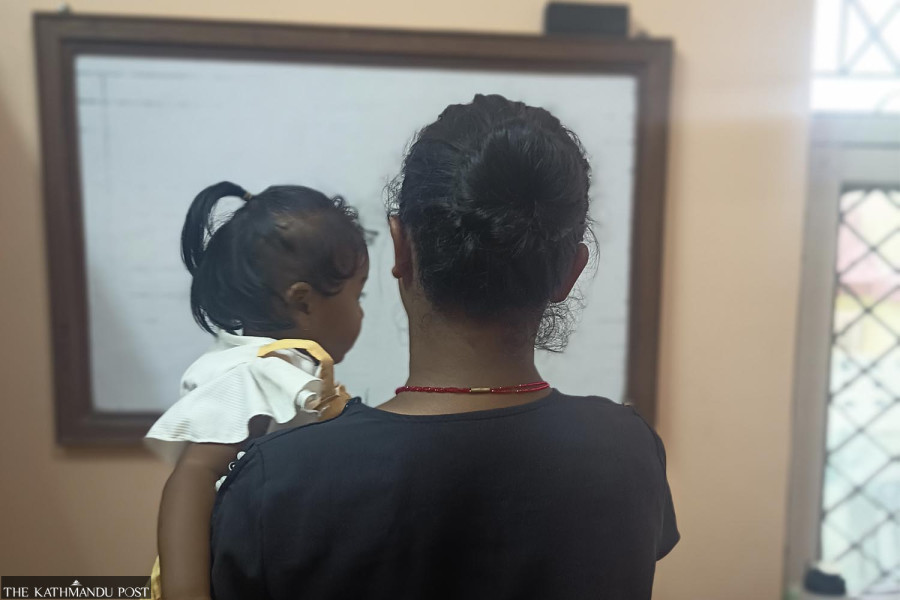

There can be no justification to delay the recognition of thousands of children as genuine Nepali nationals.

The Constitution of Nepal guarantees every child the right to name, birth registration and identity. Section 4 of the Act relating to Children, 2018, also states that every child has the right to identification and birth registration. But, unfortunately, for more than 5,000 Nepali children, this constitutional provision is limited to paper, as they are yet to get their birth certificates. In the absence of a document as basic as this, children are denied not only educational opportunities and other training programmes but also citizenship, effectively rendering them stateless. One cannot access any job, learn skills, get married, inherit property, or get health services, among other things, without citizenship.

The root of the problem is the government’s apathy to build a robust civil registration system. Even when there is no legal barrier to guaranteeing birth registration to undocumented children, local officials overlook the constitutional provision and only follow the Civil Registration Act and the National Identity Card. They ask for documents that the parents never had. For instance, children born to parents who lack citizenship and are born in a different location to their parents’ birthplace must face ward officials who are unconvinced of their birth in their locality, even though there are people who can vouch for these children.

Further, even as the Civil Registration Act assigns the concerned ward chairperson at the local level to provide the information needed for birth registration in the absence of an informant, many are reluctant to empathise with these children, especially with those who are over 16 or whose one parent, particularly a mother, is alive (in this case, they ask where the father was born). Children born to families living on the streets and migrants face similar hurdles. And problems are even more dire for those whose parents have already died and know nothing about their ancestral roots.

As vulnerable groups, undocumented children must receive exceptional care and support. Nepal is obliged to several international laws that protect these children. Take the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which clearly states the right to acquire certification for children. Nepal ratified it in 1990, but it is one thing to pledge, and another to follow through. The state’s neglect towards undocumented children is so serious that, despite thousands of them being undocumented, the issue is not yet part of the national discourse. Nor are there efforts to resolve the insensitive and unaccountable practices at the local offices.

By 2030, Nepal aims to secure legal identification for all, including birth registration, as part of the UN Sustainable Development Goal 16.9. Additionally, in its national 15th periodic plan, the country plans to ensure 100 percent birth registration by 2030. These goals, however, will remain elusive without significant reforms. Taking cues from experts, authorities must streamline the registration process of every child at their birthplace through a clear law.

Some local NGOs have successfully conducted registration programmes by persuading local officials; concerned government bodies must coordinate in such initiatives. Many undocumented children would be relieved if only local officials could be sensitised on the life-long difficulties faced by children without right papers. Strengthening awareness and outreach of the importance of registration, especially among families in rural and marginalised communities, is vital too. A 2023 human rights report by the United States Department of State estimated that 6.7 million people in Nepal had no citizenship. This is alarming. There can be no justification—legal or moral—to continue to delay the recognition (and thus deny the rights) of thousands of children who are genuine Nepali nationals.

15.62°C Kathmandu

15.62°C Kathmandu