Sports

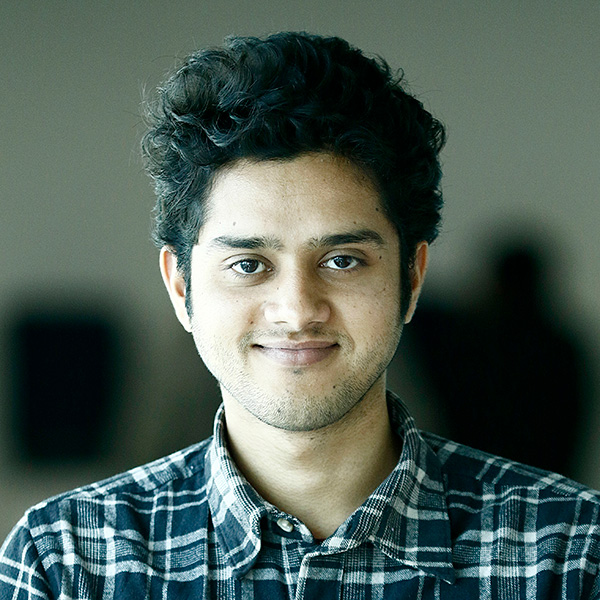

Powerlifter Bikin Joshi continues to set new benchmarks

The athlete, who has never lost a powerlifting competition, raised the bar with a bench press world record at the Asian Powerlifting Championship last month. But for all his triumphs, he had to defeat his own demons first.

Timothy Aryal

Bikin Joshi steps onto the stage of the Asian Powerlifting Championship calm and ready. He bends over to touch the floor with his hand and then takes it to his head as a mark of respect to the platform. He outstretches his hands and looks up into the heavens—his signature gesture.

“This is a world record attempt for Bikin Joshi,” announces Sukadev Karki, the founder of Nepal Youth Fitness and Calisthenics (NYFC), which partnered with World Powerlifting to organise the event in Kathmandu from August 15 to 17. “169 kg! Come on guys, give it up, give it up for Bikin.”

The crowd erupts, but by then, Joshi has already entered “the zone”, as he puts it, a flow state where he hears nothing and sees nothing, except for the loaded bar above his chest. This would be a movement he had practised countless times in the gym and, predictably, the lift goes smooth, receiving three whites, a cent percent result. Bikin Joshi becomes the first Nepali athlete to hold a world record under an international powerlifting federation.

In Nepal’s powerlifting circles, Joshi is known as ‘The Bench King’. While Nepali powerlifters are considered to have a weaker bench press, Joshi keeps on punching above his weight. He has bench-pressed up to 175 kg in the gym. Even athletes 20 or 30 kg above his category can’t match his bench press prowess.

In powerlifting games, athletes compete under three lifts—squat, bench press and deadlift, collectively referred to as SBD. The winner is the one who clocks the highest total in all three lifts combined. While Joshi set a world record in bench press in the under-69 kg category, he set national records in the other two lifts, with a 220 kg squat, well over thrice his bodyweight of 68.7 kg, and a daunting 251 kg deadlift. His total of 640 kg is just 12 kg shy of the world record total in his category. (Karki informed that the federation is currently verifying the results of the championship, and Joshi’s record would soon be recorded on its website.)

Joshi cites “self-belief” as the secret to his success.

“If you are dead certain the lift goes up, it will inevitably go up,” Joshi told the Post recently. “But if you have even an ounce of doubt, then the lift becomes 50-50.” A slight error in form can tip the balance of the lift. But so can an error in mindset, a lack of self-belief.

“Powerlifting is as much a physical sport as it is mental,” Joshi observed. “It’s also about resilience. As Mike Tyson puts it, everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face. Powerlifting is about what you would do after you get punched in the face.”

Before attempting a big lift, powerlifters are confronted with a fight-or-flight state—whether to grind it or to give up. Joshi cites how the English strongman Eddie Hall used mental imagery to pull off the record 500 kg deadlift by picturing the weight as a car about to crush his children. Midway into his 251 kg deadlift, Joshi had his legs wobble, and he had to grind it to lock it out.

“At that time, I thought of how my friends would mock me if I couldn’t pull that off,” Joshi said, half-jokingly. But on a sombre note, Joshi said he was really grateful for the support of his friends and mentors for helping him come this far.

Joshi didn’t set out to be a powerlifter. In the early days after he joined the gym, he was focused on bodybuilding. He had a reason to. As a skinny teenager weighing just 47 kg, he often felt inferior among his peers. He wanted to play sports such as football and basketball, but a lack of physicality meant he would fail to even make the cut on the class team. Studying at the Sainik Awasiya Mahavidyalaya in Bhaktapur, he was among the shortest and weakest students in his class.

A trip to a relative’s house in Itahari during his +2 winter break made matters worse. He was mocked for his skinny physique, he recalls. “The first thing I did after returning to Kathmandu was join the gym,” he said.

A couple of years after that, he contested the Mr Kathmandu bodybuilding competition in 2019. He made it to the Top 15 but not beyond. A few months later, he contested the Mr Bhaktapur competition, but he couldn’t even make it to the Top 5 out of seven competitors. He had spent thousands of rupees on nutrition and supplements by then, but he had little to show for it. Having come from a family of modest financial background, he felt bad about wasting so much of his parents’ money.

Dejected, he decided to put an end to his bodybuilding career. It was about the time when the coronavirus pandemic had started, and gyms were closed. The pain of failure was coupled with lockdown restrictions and an inability to work out at the gym. And Joshi went through a period of crushing depression.

“All I would do was eat chips and watch TV series until five or six in the morning,” he said. “An indifference to nutrition had taken a toll on my body.”

Meanwhile, once the lockdown restrictions were eased and Joshi began to work out, he started to feel better and stronger. And a few months down the line, he decided to try himself at powerlifting, with the BSAL Bhaktapur district-level powerlifting competition. To everyone’s surprise, and his own, he won the competition, not just in his category but also the overall title. He had pulled off a 210 kg squat, 135 kg bench press, and 220 kg deadlift. He hasn’t looked back since.

Of the six competitions he has become part of since, he has won all, missing out on the Overall Champion title in only one, in the OX Classic in 2024. In the NYFC Classic I, Joshi once again bagged the overall title. But after that, he injured his QL muscles on his back. It was another setback for the budding athlete. He couldn’t squat and deadlift for five months. But he could still bench-press. And so he turned the setback into an opportunity, seeing a huge 15 kg jump in his bench press numbers, from 150 kg to 165 kg.

“Bikin is one of the most promising players in powerlifting that we have,” says Karki, who Joshi considers a mentor. “He is young and he loves competition. In fact, he has never lost one… He has the potential to bring medals for the country even in competitions under bigger powerlifting federations.”

Joshi today has come a long way since those dark and lonely days when he could scarcely feel good about himself. He reports feeling stronger today than ever before.

Joshi has now set his sights on the World Powerlifting Championship to be held in Sri Lanka in November. Sustaining in the fitness industry in Nepal can be hard even for champion athletes like Joshi. Also an NYFA-certified personal trainer, Joshi provides in-person and online training. He is also looking for a sponsor to support his preparation for the upcoming battle on the world stage.

Within a week of the Asian Championship, Joshi was back to work, with a new training regimen and a new goal. “Feeling strong… same grit but now more hungry,” he captioned an Instagram story showing him deadlifting 220 kg for three reps. “A lot to improve.”

8.69°C Kathmandu

8.69°C Kathmandu