National

‘For you, he might be the ‘accused’ but for me, he is a criminal’

A tale of a society that celebrates rape-accused while the victim struggles to breathe free air.

Tufan Neupane

If cricketer Sandeep Lamichhane’s fall from grace was noteworthy in the history of Nepali sports, his release on bail from jail followed by the subsequent lifting of his suspension by the Cricket Association of Nepal (CAN) was appalling.

While much of the cricketing fraternity and rape-accused Lamichhane’s supporters cheered him from the sidelines, the victim of his alleged crime was forced into hiding.

Gaushala-26, as she is identified by the code name assigned by the law enforcement agency, says she has been hiding for the past five months and counting. “I haven’t been able to enjoy sunlight because I have to stay hidden. But I have been following what’s happening outside. I can see people sympathising with the perpetrator, presenting him as the victim,” she says. According to her citizenship certificate details that Kantipur, the Post’s sister paper, is privy to, she is still a minor.

“For you, he might be the ‘accused’ but for me, he is a criminal. The day he came out of judicial custody, he was celebrated as a hero with garlands and cheers. But no one thought about me and how I am living. This begs the question of the kind of society we are living in.”

Gaushala-26 has been facing a barrage of questions since she filed a case against the cricketer on September 6, 2022, at the Metropolitan Police Circle, Gaushala. The most disturbing ones are the ones that question her intent—why did she agree to go out with a man she wasn’t very familiar with? Why did she spend the night at a hotel?

In a classic case of victim-blaming, the minor was blamed for what happened to her; the society at large held her responsible for being raped placing the burden of proof in the court of public opinion on her even before her case reached the judicial court.

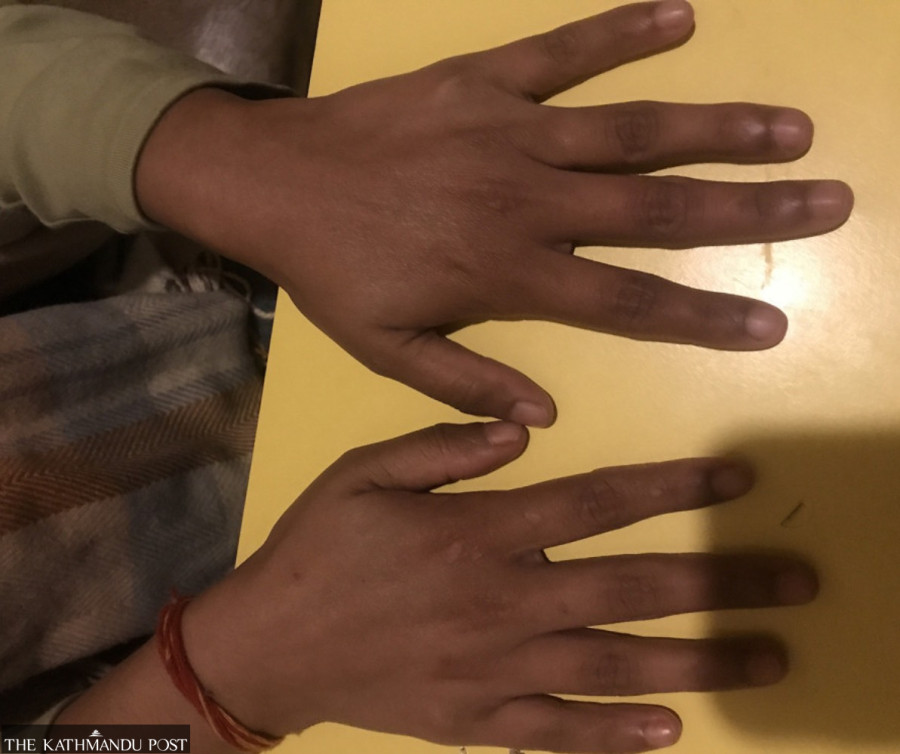

She tells of her harrowing account, in presence of her two older cousins, with permission of her mother and her lawyer.

Never in her young life had she imagined she would make the headlines for the injustice meted out to her; deal with the police, lawyers and court and sit for a social media trial.

“I had not imagined such a scenario, such a life where I had to go through hell and back,” she says.

August 21, 2022, was a regular day for the grade 12 student except that later in the day she was going to meet Lamichhane, a persona she was a big fan of.

“That day, I told my friends in college that I was going to meet Sandeep Lamichhane today,” she says.

Gaushala-26 made acquaintance with Lamichhane through Snapchat, a social media platform. They had been chatting online on and off since August 17. Prior to their meet-up on August 21, Lamichhane had made several requests to meet in person. She had been mulling over the requests for several days before she agreed to meet him. “Even then I first denied his request. I wasn’t sure. But Lamichhane was persuasive. He said he will be flying to Kenya the next day, then he would be in Jamaica to play the Caribbean Premier League,” says Gaushala-26. “Then there was the Big Bash League auction, he told me. If he was selected, he would be away for one to two months. He stressed that if we didn’t meet that day, we wouldn’t be able to meet at all.”

The minor gave in to Lamichhane’s persuasions. She told her friends about the meet-up and all of her friends were excited for her and encouraged her saying this would be the right opportunity for her to take photos with him.

“I had heard he was arrogant and an egoistic person. But I couldn’t resist the pull of meeting a ‘star’ and taking pictures with him, especially since he was nice to me. I decided to meet him,” she says.

At around 2:30 on that Sunday afternoon, she received a call from an unknown number. It was Lamichhane calling from a ‘teammate’s number’. He didn’t like to use his personal number to call or text, he told Gaushala-26. “On that call, he told me he was going to a meeting in Satdobato and that we should meet after the meeting,” she says. “We continued texting on Snapchat.”

She informed her roommate from her hostel that she would try to be back before 8pm. “I told her if I get late, please open the door for me since the hostel gates closed at 8pm. This was the first time I was going out in the evening since I started living in the hostel,” she says.

Gaushala-26 has not had an easy life growing up. Her parents, who fell in love and married against their families' wishes, are long separated. When her father remarried, her older brother went to live with him in another city while she lived with their mother just outside Kathmandu. Her mother, who worked as domestic help in various households, to make a living for herself and her daughter, could not seek legal recourse after separation from her husband for their marriage was never legally registered.

“So my mother worked hard to send me to school,” says Gaushala-26. “After completing grade 10, I wanted to come to Kathmandu for further studies but my mother could not afford to send me to school here.”

Her desire to come to Kathmandu and study in a reputed college so that she can break the cycle of poverty her mother and she was encircled in, pushed her to apply for scholarships in three renowned colleges in the capital. One of the colleges accepted her application and decided to give her a scholarship. A person living abroad agreed to support her education and sent her Rs3000 a month as a sponsorship. “But that was not enough to live in Kathmandu. I had to find a place to live so I started looking for the cheapest hostels for girls,” she says. “I found one that charged Rs8,000 per month but even that amount was out of my budget. I told the hostel operator about my situation. She said she would keep me as her daughter without me having to pay rent if I helped her with house chores.”

After a while, the hostel operator found her a job at a local computer training institute as an instructor. “In the morning I would learn accounting programmes at the institute and teach the students of the same institute in the late morning, and then go to college. They offered me Rs8,000 as remuneration,” says Gaushala-26. “I preferred this job than working as a house help to earn my lodging and food.”

Gaushala-26 now needed a bank account to regularly receive her monthly salary so she went to her father to acquire her citizenship. Her citizenship was issued on June 29, 2022. The birthdate on the certificate says June 1, 2005. According to this, she was only 17 when the incident happened.

Her acquaintance with Lamichhane began only in August, months after her citizenship was issued, but there have been talks, especially on social media, about how she acquired her citizenship as a minor only to frame Lamichhane.

When she sent Lamichhane a friend request on Snapchat, Gaushala-26 had not imagined the repercussions clicking the ‘add friend’ button would have in her life.

Before the Snapchat communication with Lamichhane began on August 17, Dev Khanal—a member of the Nepal Cricket Team—whom Gaushala-26 had befriended on Snapchat a couple of months ago, sent a picture of Lamichhane sitting on a bed playing the guitar. Khanal had introduced Lamichhane as his roommate and sent her pictures of the latter’s Snapchat ID. Gaushala-26 initially did not give it much thought but later she sent a friend request to Lamichhane. He accepted her request immediately.

Conversations between the two soon began.

The two-way conversations with Lamichhane mostly revolved around their life stories—she shared her hardships with him and he sympathised with her.

“My college supported me. Most of the time, I didn’t have to buy books. The teachers would give me books sent by the publishers. While one of the teachers bought me my uniform the other bought me my school shoes,” she says. “Things such as stationery would be in ‘lost and found’ so when I told my teacher I didn’t have a good calculator, they gave me one left behind by one of the students from a well-off family. That was how my college life was going and I had told Lamichhane about all of that.”

On Sunday, August 21, when Lamichhane came in a white car to pick her up, she says she was “impressed”. “All I could say was ‘Wow’,” she recalls.

Lamichhane requested her to sit in the car, but hadn’t mentioned their destination. They talked about the tournament he was leaving for the next day. “Once we reached Koteshwar, I asked where we were going. He said—let’s see!” Gaushala-26 says. “That was the first time I was leaving my hostel at that hour in the day. I didn’t know it would be my last.”

The car started, and the journey had begun. From Lokanthali, the car took the inner road. “Once we reached there, he decided to go to Nagarkot. I had never been there. We had left the main road and were on a narrow lane, where it was difficult to manoeuvre the vehicle,” she says. “When I think back on that day, he may have taken that route to cause delays.”

Once they reached Nagarkot, Lamichhane tried to coerce Gaushala-26 to drink, but she refused. He urged her to try ‘Hookah’ he had brought for himself, but she refused. But the conversation was amicable. “So far, he was fine. Since I had shared my stories with him, he was trying to motivate me,” she says. “But now when I recall those conversations, I think he was manipulating me into trusting him. Since he knew about my background and my financial condition, he tried to level with me saying that he too comes from a background similar to mine and to look where he was today. He said if he could do it, so could I.”

She thought that what she had heard about Lamichhane being arrogant and egotistic was baseless. “I thought people misunderstood him. A high-profile person was talking to me so nicely. Back then, I was thinking I will tell my friends how wrong they were in presuming Lamichhane was full of himself.”

Gaushala-26 recalls how the hotel staff asked Lamichhane several times if they should book a VIP room for him. She said she needs to return to her hostel before it’s too late but Lamichhane never said he didn’t need the room the hotel staff were offering. “Several times he asked them to come back after 5 or 10 minutes. I wasn’t planning to go to Nagarkot. I didn’t even know that a cricketer who was going abroad the next day would have so much time. I had thought I’d meet him and take a picture, but it was close to 11pm. I started to insist that I had to return,” she says. That’s when Lamichhane got angry, she says. “He told me I can’t ‘digest’ it—the good things happening to me. He started humiliating me by saying that he has taken a person like me to a hotel I could never afford. I will never forget it. He said nice things are not palatable to the likes of me.”

After the argument, they left Nagarkot.

When they reached Lokanthali, she sent a text to her friend. “I was afraid of the questions I would be asked for returning so late. I told Lamichhane that it would be difficult for me to return to the hostel at such a late hour,” she says. “He said he would leave me at a hotel and he would return to the hotel where other players were staying at.”

To avoid being asked uncomfortable questions and to avoid reprimand from the hostel operator, she agreed to go to the hotel. “I thought I would sleep at the hotel and go to the hostel the next morning,” she says. “Then I tried to take his picture while we were talking since that was the main objective of meeting him. But he snatched my mobile phone and didn’t let me take pictures. Even then I didn’t think anything was amiss. I thought he would get in trouble at the camp for staying out late too.”

Lamichanne then placed a call to one Anish Shrestha of Kathmandu Inn Hotel at Tilganga. “He asked him to prepare “that” room. I told him to ask them to prepare two separate rooms if I were to stay there the night but he told me there was only one room available at the moment.”

“Then he said he would drop me at the hotel and he would leave,” she says.

At the hotel gate, before dropping her off, Lamichhane asked her to put a mask on. “I didn’t have one so he gave me the one he was using insisting I wear it,” she says.

Lamichhane went to park the car after sending Gaushala-26 towards the reception where Shrestha was waiting with a key to the room. She went to the room to find that it was a single room. “After a while, he came to the room. The air conditioner in the room wasn’t working so he said we should move to another room. That’s when I realised he lied to me earlier when he said there was only one room available,” she says. “I told him I will stay in this room even if the air conditioner is not working and that he should go to the other room. He said he would go after a while.”

Gaushala-26 had had a long day. Spending all morning at the office, then attending college, and then the unexpected trip to Nagarkot and back had exhausted her. She hadn’t even had her dinner which left her more exhausted.

“He said he would leave the room in a while. I was sitting on a chair and he was on the bed. He said if I was tired, I should sit on the bed,” she says. “When I asked for my phone back, he said he had left it in the car. By then I was too tired to ask him to bring it. I soon began dozing off.”

The next thing she was aware of was Lamichhane pressing against her, feeling her. “He was forcing himself on me. I tried to throw his hands away but I could not. He then began to penetrate me. Once he was done, he went to the bathroom. I could feel his semen all over my body. When he came out of the bathroom, he brought a bunch of tissue papers and threw it at me asking me to clean myself up,” she recalls.

According to Gaushala-26, she was told not to tell anyone about their meeting. “After the incident, he threatened me and asked me not to tell anyone about it,” she says. “I couldn’t leave. I didn’t even know where I was.”

Then on September 6, 2022, she went to the police.

“Several people are questioning me why I didn’t go to the police immediately. In movies, rape victims are shown with blood on them; their clothes are torn and hurt badly or killed. So until those things happen, people assume it’s not rape. I want to ask those people if I were killed, would they believe me?”

“What happened that day was not by my consent. I didn’t consent to being raped either with my actions or my words. Going to Nagarkot was not my plan, neither was staying at the hotel. It was Lamichhane all along. He committed a premeditated crime.”

In Nepal, seven women and children are raped every day. Nepal Police’s statistics for the fiscal year 2021-2022 show the number of incidents of rape, kidnapping and rape, rape and killing stood at 2,461. However, since most incidents of rape survivors are not made public, people assume that such incidents don’t happen.

In the case of rape survivors, the victim is asked to prove that the crime against her actually happened.

“I was in such a state that if you ask me to recall the colour of the room, I wouldn’t be able to tell you. I don’t remember how this atrocity began and how it ended,” she says. “But he knew exactly what he was doing. Later that night, he raped me again. My hair was waist-long. He pulled my hair and made me do things I wasn’t comfortable with. Unable to do anything to stop what was happening to me, I began to cry. After that, he hit me badly asking me to submit to him. A few days later, when the shock had started wearing off, the first thing I did was cut my hair.”

In the morning after the dreadful night, she took a picture of Lamichanne’s license plate and sent it to Dev Khanal. “After that Lamichhane called and yelled at me for taking and sending the picture,” she says. A few minutes later, he removed her from his Snapchat friends’ list.

Gaushala-26 did not go to work or college for the next few days. When she built up enough courage, she told her close friend about the incident. “He did not believe me. He said it must have been my fault. My friend did not trust me,” she says.

A few days later she went to meet her mother. “After a couple of days of staying with her, I asked her why she wasn’t curious about my visit. She said it’s good that I was home because she missed me,” she says. “I then told her about what happened. She slapped me hard.”

“My mother herself was a victim of violence. She was worried about me, about how I would not have any prospects of marriage,” she says. “At first, my mother said I should forget about it because he was a powerful man, but I convinced her that I must speak up because if an educated person like me doesn’t, who will?”

On September 6, she went to file a complaint against Lamichhane in the company of her brother.

On September 7, the Kathmandu District Court issued an arrest warrant against Lamichhane.

Following the arrest warrant, the Cricket Association of Nepal (CAN) suspended the globe-trotting leg spinner. When he was accused of rape, Lamichhane was in Trinidad & Tobago to play the Twenty20 franchise Caribbean Premier League (CPL) from Jamaica Tallawahs.

Lamichhane wrote on Facebook the same day claiming that he was innocent and would return to Nepal to seek justice. However, after he mysteriously disappeared, Nepal Police circulated an Interpol diffusion against Lamichhane.

On October 1, Lamichhane announced that he would return to Nepal on October 6 to face legal charges. Soon after he landed at the airport, he was arrested by officials at the Department of Immigration and plainclothes police.

Meanwhile, Gaushala-26 says that there have been efforts to change her statement. “Lamichhane’s brother went to my mother pretending to be my lawyer. He told her we can’t win the case and offered settlement money,” she says. “They told me they will help me settle wherever I want—the US or Singapore. They offered $500,000. I didn’t accept.”

“The victim in Paul Shah’s case was made to change her statement. If I change my statement, other rape victims and survivors like me will never see justice. We will continue being raped,” says Gaushala-26.

When she first left home for Kathmandu, her mother had asked her to get an education so she can live an easier life than her mother ever could. “My mother was willing to sell her kidney to give me a shot at higher education. She inspired me to pursue my dreams and I will continue living up to her expectations for me.”

A case filed at the Kathmandu District Court has charged Lamichhane of raping a minor. On November 4, 2022, the trial court sent him to judicial custody. However, on December 14, the Patan High Court released him on Rs2 million bail. The attorney general's office has moved the Supreme Court challenging the high court order demanding that Lamichhane be kept in judicial custody until the final hearing of the case.

Meanwhile, the Cricket Association of Nepal (CAN) has lifted Lamichhane's suspension and invited him to train at the national team’s close camp.

Nepal is hosting Scotland and Namibia in the Tri-Series fixture of the ICC Men's Cricket World Cup League 2 from February 14 to 21.

(This story was first published in Kantipur Daily on January 30. Translated from Nepali with the help of Somesh Verma.)

10.28°C Kathmandu

10.28°C Kathmandu