National

Women and activists see red over pink tax

The government last fiscal year collected Rs342.31 million in revenue from imports of sanitary napkins. Calls grow to ensure easy accessibility of menstrual hygiene products.

Krishana Prasain & Aakriti Ghimire

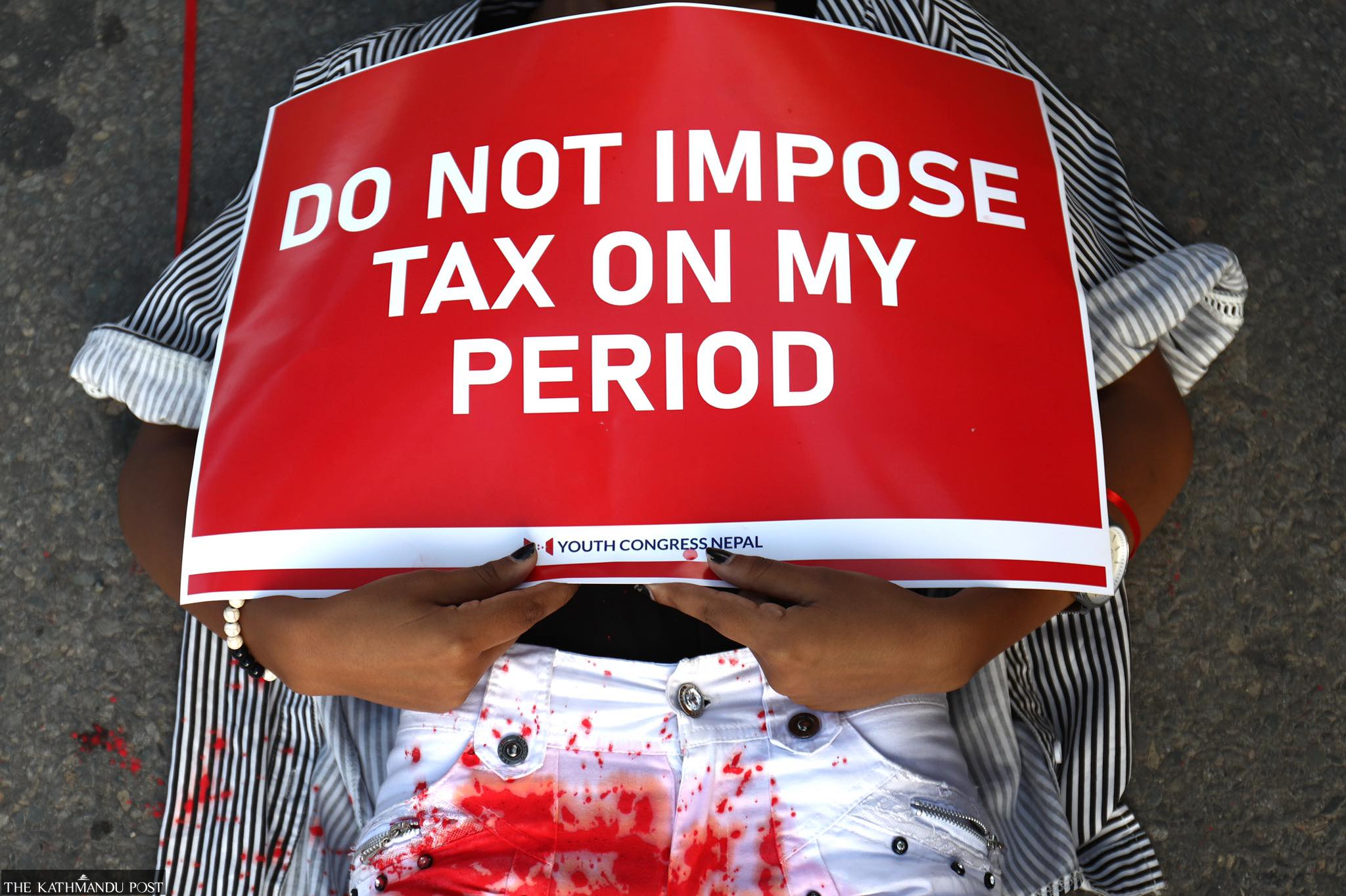

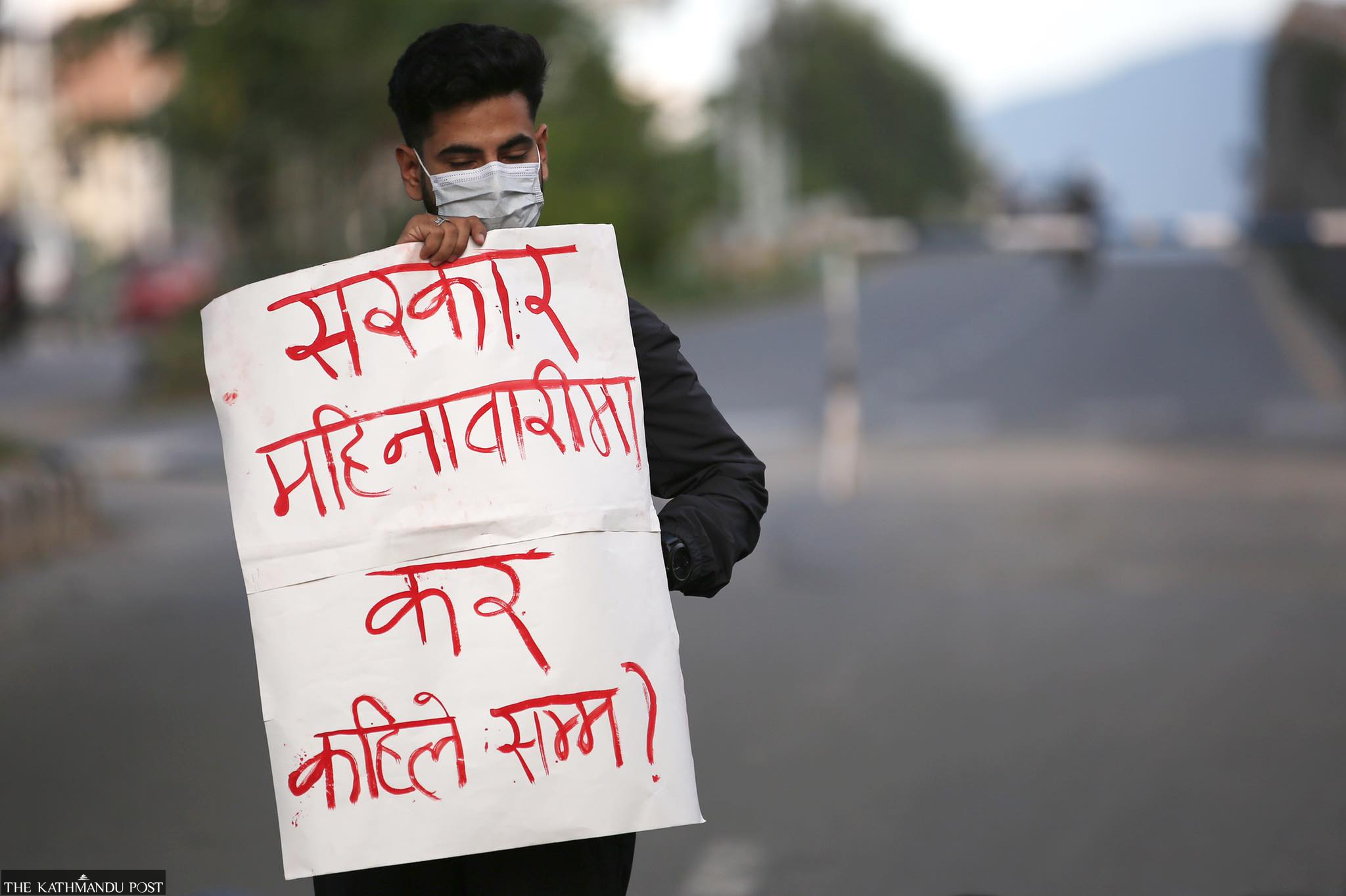

On Thursday, a group of 20-25 youths staged a protest at Maitighar in Kathmandu to press the government t0 scrap tax on feminine hygiene products, including sanitary pads.

The protest was prompted by some social media posts suggesting that the government had increased tax on sanitary napkins. Amid the public outcry and protests, the government made it clear that tax has not been hiked on such products.

Nevertheless, this has once again reignited a public debate on the taxation of feminine hygiene products like sanitary napkins and their easy accessibility to women.

“With each cycle, I need two packets of pads, which cost a lot. I’m having to cut down my budget on food and other expenses because of the high prices of sanitary pads,” said Ramita Jaiswal, a second-year MBBS student at Lumbini Medical College.

Jaiswal, a native of Simraungadh, Bara, has three sisters who are financially dependent on their parents. “I make do with a limited amount of money that my parents send every month, and I can’t ask for more. Covid-19 has already created a lot of financial difficulties, and the ever-rising price of pads places quite a burden on our family expenditures.”

According to the Department of Customs, the country imported sanitary pads worth Rs1.17 billion in the last fiscal year and generated Rs342.31 million in revenue for the government, which is close to 30 percent. Similarly, in the fiscal year 2019-20, Nepal imported sanitary pads worth around Rs2.18 billion for which the government raised revenue worth Rs645.72 million.

According to Narayan Prasad Sapkota, director general at the Department of Customs, 15 percent customs duty, 13 percent Value Added Tax (VAT), and an additional 1.5 percent VAT on customs duty are charged while importing the products.

He said that there have not been any changes in customs duty for more than a decade.

“The issue should have been raised in the past, as the customs rate has remained unchanged for years,” he said. “I don’t know why this issue is being raised now.”

Those advocating sanitary pads’ easy accessibility say the government can do without the amount it generates through customs duty on these products, or even if it is not scrapped totally, the duty can be slashed so as to ensure their easy reach.

However, there is a need for an understanding among the policymakers that the product is an essential item, not a luxury thing.

The lack of proper menstrual hygiene and sanitation often leads to increased school dropouts and low productivity at the workplace, hence globally, activists have been pressing their governments to scrap tax on such products.

A report published by the Ministry of Women, Children and Senior Citizens highlights that 83 percent of women lost their jobs and income because of the pandemic, and there has been a 337 percent rise in the number of women not involved in any paid work. The pandemic has disproportionately affected women in Nepal. With the increase in income inequality divide, many women are compelled to exhaust the remaining of the meagre savings they had, borrow money from informal lenders, borrow food and reduce the number of daily meals.

Period poverty is a global issue, whereby women do not have access to “safe and hygienic menstrual products”. Historically, women and young girls in Nepal have suffered from a lack of knowledge on menstruation and menstrual hygiene, access to safe and affordable menstrual products, and social ostracisation. Period poverty became more visible during the pandemic in Nepal.

“Sanitary pads do not fall under ‘essential’ items—which include medicines, medical supplies, contraceptives, and condoms—that are exempt from VAT. They, instead, are taxed as luxury items,” said Shubhangi Rana, co-founder of Pad2Go Nepal, a for-profit social enterprise that has been an active voice against the luxury tax imposed on menstrual products.

“Because of that, during the lockdowns, sanitary pads didn’t make it to the villages. Many women then resorted to rags, old clothes, or other unsanitary products during menstruation, which is a health hazard.”

Pad2Go Nepal started a petition last year for the removal of 13 percent VAT on menstrual products in Nepal. Rana said that they, however, understand the impacts of such VAT removal on the domestic economy.

“It creates an unfair advantage to imported menstrual products over domestically manufactured ones. That is why it is essential to remove the VAT, with policies that protect domestic manufacturers,” said Rana.

According to Rana, her organisation’s main agenda is not just tax removal; it’s rather ensuring the affordability and accessibility of menstrual products for women across Nepal, for which, she said, there needs to be strict monitoring.

And tax removal can be a stepping stone towards increasing accessibility to products.

Menstruation is a normal biological function. To menstruate is not an option, but an occurrence that is inevitable, that signifies women’s reproductive capabilities.

Jaiswal isn’t alone in expressing her frustration at the government’s taxation policies.

“I bought a sanitary pad yesterday. It cost me Rs135. Even for the Safety pads that I used to buy at Rs45, I paid Rs 58,” said Aarju Kharel, who works at SMS Clinic, Hattisar. “As a working woman, I need to maintain my own finances. My salary isn’t increasing and this sudden hike in prices is shocking. This is absolutely ridiculous.”

On August 10, two second-year students of Kathmandu School of Law, Abhyuday Bhetwal and Shreena Nepal, filed a writ in the Supreme Court demanding the removal of menstrual products from luxury goods and their categorisation as essential goods.

On August 12, the first hearing took place, where the court asked the duo to collect written responses from all four ministries—Ministry of Finance; Ministry of Women, Children, and Senior Citizens; Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs; and Ministry of Health and Population—against whom the writ had been filed. However, the Ministry of Finance did not provide any written answers by the deadline of September 10.

The court has provided an extension until October 1 to collect a written response from the Finance Ministry.

Research shows that the law has a crucial role to play in addressing the problems around menstrual hygiene management, as observed in Colombia, India, and the United States.

India scrapped its 12 percent tax on all sanitary products in July 2018, in what is hailed as a landmark move by the government in an attempt to increase women’s accessibility to feminine hygiene products. The Maldives followed suit in December 2018, exempting taxes on all menstrual products—sanitary towels and sanitary pads, panty liners, sanitary belts, internal devices for menstruation, and maternity pads. The same year, the Constitutional Court of Colombia struck down the 5 percent tax on menstrual products, declaring it unconstitutional. It also mandated that the city of Bogotá provide menstrual hygiene products to homeless women. In 2020, Scotland passed a bill to provide menstrual products for free for anyone who needs them.

Feminine hygiene products are not accessible to millions of rural women in Nepal not only because of a lack of awareness but also because of the price.

Kritagya Kriti, a 21-year-old volunteer at Himalayan Education And Development (HEAD Nepal), a non-profit organisation that works for persons with disabilities, in Simikot, Humla, shared her experience regarding menstrual hygiene management in the remote district.

“The Padelux pad whose maximum retail price (MRP) is Rs60 is sold at Rs150, and Stayfree is sold at Rs250,” Kriti told the Post over the phone. “I was shocked to learn about the prices of the items that are extremely essential.”

Retailers attributed the high price of such products to the cost they have to bear to bring them to the district.

Kriti said when she enquired the airlines about cargo charges, she found that the cost stood at Rs110 per kg. Despite adding the cargo charge per sanitary pad, the prices that the pads were sold for were ridiculously high, and yet the retailers could get away with it, said Kriti.

“The consequences of such high prices have led to extremely poor menstrual hygiene among women in Simikot. Some women here use rags, others use old clothes. There are quite a lot of women who don’t use anything.”

Kriti, a native of Mills Area, Janakpur, who went to Simikot a month ago, said the situation made her realise how far behind the Nepali state is in providing equal access to women.

“If we can remove taxes on products such as medicines and contraceptives, we can do it for sanitary products as well,” she said. “Without sanitary products, people die, they literally die.”

Mohna Ansari, a former member of the National Human Rights Commission, says there is a lack of understanding among policymakers when it comes to feminine hygiene products.

“Sensitivity towards law and policies related to women is extremely weak in Nepal's bureaucracy,” Ansari told the Post.

The government says its policy has been to promote local industries when it comes to sanitary pads. In the budget for this fiscal year, the government has announced a hundred percent tax rebate for those setting up companies to manufacture sanitary pads for three years from the date they start production. Thereafter, the companies will get a 50 percent tax waiver for two more years, according to the government.

Advocates of easy access to menstrual hygiene products, however, worry about the quality of the products, given lax monitoring in Nepal. Then there are also questions regarding individuals’ choices. If anyone wants to use imported sanitary napkins, the person should have the right to do so and to ensure that it does not put an extra financial burden, the tax regime needs a revision, they say.

Local manufacturers say the price of menstrual hygiene products manufactured in Nepal too has shot up due to the rise in the price of raw materials.

“Nepal imports 100 percent raw materials to make sanitary pads, mainly from China, followed by India, Indonesia, and Japan,” said Bijay Pokhrel, director of Softy Hygiene. “The rising dollar price has increased the price of raw materials. The freight charges have also gone up globally due to which the price has been impacted. A container charge has reached Rs900,000 which used to come at Rs150,000.”

According to Pokhrel, if the government does not provide a waiver on VAT and tax while importing raw materials to make sanitary napkins, the price of sanitary pads could go up 35-40 percent in the coming months.

“The customs duty on raw materials and the finished product is almost the same and this has also impacted the price marking,” said Pokhrel.

Yadav Ghimire, chairman of the company, said that the customs is imposing 15 percent duty on the import of raw materials to make sanitary pads with 13 percent VAT.

“The customs rate has not been increased,” he said. “We have been lobbying with the secretaries of the Ministry of Finance and Revenue Department to decrease the customs duty to zero.”

Thursday’s demonstration at Maitighar was organised by Youth Congress Nepal and Pad2Go Nepal, with the slogan #RaatoKarMaafGar, or “exempt blood tax”.

“Taxation on menstrual products violates the constitutionally guaranteed rights to safe motherhood and reproductive health,” said Binod Deuba Thakuri, a central member of the Youth Congress Nepal.

“I am from Doti, and I have seen women back home who cannot afford these menstrual products. It’s not just about scrapping the tax, it is about making menstrual products affordable and accessible to women across Nepal,” said Thakuri. “This isn’t a tax on menstrual products, it’s a tax on menstruation and menstrual blood itself.”

Proponents of easy availability of feminine hygiene products say when it comes to equal access for women, the problem runs deep in Nepal.

“Women are neither consulted prior to making these policies nor are they at the decision-making tables,” said Rana of the Pad2Go Nepal, which has impacted the lives of 40,000+ young girls. “Having talked to multiple stakeholders, the problem we saw is that women aren’t a part of the solution. Where are women in these meetings that decide what is an essential product and what isn’t? Where are women in these meetings to determine what should be taxed, and how much?”

Ansari, the former rights commissioner, said that at her initiative, a recommendation was made that the government not put sanitary pads on the list of luxury items.

“We had recommended that the government should not impose a tax on menstrual hygiene products,” Ansari, who served at the national rights commission from October 2014 to October 2020, told the Post. “The government never read the recommendation, I believe.”

13.38°C Kathmandu

13.38°C Kathmandu