National

Oli returned to power on nationalistic plank. But he seems to be failing to adhere to the hope he sold

Despite a strong government that could keep foreign meddling in the country at bay, observers feel that instability in the ruling party could go against the national interest.

Anil Giri

At the end of April this year, Nepal Communist Party chair and Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli was under pressure from within his party to resign. Immediately, Chinese Ambassador to Nepal Hou Yanqi met the President, the prime minister and top leaders of the ruling party.

Oli survived the demands for his scalp.

In July this year, calls for the prime minister’s resignation resurfaced. Again, Hou got busy meeting President Bidya Devi Bhandari, Prime Minister Oli, party chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal, senior leaders Madhav Kumar Nepal and Jhala Nath Khanal.

Oli once again fended off his detractors.

This time round Hou so far has just met Oli. With still more than a week to go before the Secretariat meets on November 28, the Chinese envoy still has time to call on Oli’s opponents in the party.

In the latest episode of intra-party wrangling in the Nepal Communist Party, the situation could be said to be slightly more precarious for Oli. Dahal has presented a political document lashing out at Oli for his “failure” to govern.

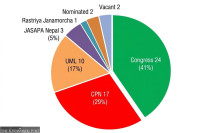

The Secretariat meeting will be followed immediately by the party’s 44-member Standing Committee meeting on December 3 and the Central Committee meeting on December 10. In all three committees the anti-Oli faction is stronger.

Hou’s latest meeting with Oli comes after the prime minister met with Samant Kumar Goel, chief of India’s external intelligence agency, Research & Analysis Wing, in the third week of October.

When the political going gets tough in Nepal, foreign “interest” increases significantly thus raising questions, among observers, why Nepali politicians fail to stand on their feet and do not remain united to stop foreign powers from coming into play.

Former foreign ministers, political leaders and diplomats have expressed serious concerns over ‘overt’ activities of foreign diplomats and officials in Kathmandu and the way the Oli administration has paved the way for them to express their interest in Nepali polity despite there being a strong government voted into power on the basis of a nationalist agenda.

“This is a sign of our failure in handling foreign policy,” said Upendra Yadav, former deputy prime minister and foreign minister who is also the leader of the Janata Samajbadi Party. “Our leaders have failed to conduct diplomacy effectively.”

What observers have found more intriguing is Foreign Ministry officials were not invited during Oli’s meeting with Goel, thereby having no institutional memory of such meetings.

According to a senior Foreign Ministry official, the ministry is unaware of the prime minister’s “unofficial” meetings with foreign diplomats usually from India, China and the United States.

“We get calls from the Prime Minister’s Office only for courtesy calls to the prime minister and for official meetings with foreign diplomats,” said the official on condition of anonymity because he feared retribution. “Therefore, we are not aware of what transpires between our leaders and foreign diplomats during these meetings.”

It was during Nepal’s political transition between 2006 and 2015 that foreign diplomats, especially Indian ones, used to frequently meet top leaders from across the political spectrum.

It was in the context of such frequent meetings that Yadav, as froeign minister in 2008, introduced a diplomatic code of conduct to check the activities of foreign diplomats including their meetings with political party leaders. But the code of conduct remained largely unimplemented.

The Oli government too is preparing to reintroduce a new diplomatic code of conduct, but it is yet to be presented at the Cabinet.

“This mess is the result of our collective failure to adhere to the diplomatic code of conduct. Our major parties are responsible for it,” said Yadav. “We thought we would stand on our own feet and make decisions independently but, sadly, this is not happening.”

The Chinese Embassy in Kathmandu has been publicly admitting meetings between Ambassador Hou and ruling party leaders. In May, according to the embassy, it was to extend China’s support in Nepal’s fight against the Covid-19 pandemic. This time, it said Ambassador Hou met Prime Minister Oli to extend Tihar greetings.

“The logic given by the Chinese Embassy that the ambassador met with the prime minister to extend Tihar greetings is laughable,” said Ram Karki, a lawmaker and deputy chief of the foreign affairs department of the ruling party. “I do not see any connection between Tihar and China.”

China’s supposed role in Nepali politics has not gone down well with the main opposition Nepali Congress either.

“It does not look good for China to take an interest in the dispute inside the ruling party,” said Nepali Congress leader Ram Sharan Mahat, who has also served as foreign minister in the past. “An ambassador represents the country, not a political party.”

Of late, another neighbour, India has also gradually upped its interest in Nepali politics although it had taken a backseat since Oli came to power on a nationalist plank, staunchly opposing the signing of a trade and transit treaty with China and India’s 2015 blockade.

After a year-long lack of meaningful communication between Kathmandu and New Delhi, Goel’s visit broke the ice and paved the way for some high-level visits from both sides.

After Goel’s visit, Indian Army chief Manoj Mukunda Naravane landed in Kathmandu in the first week of November. Though his visit was for receiving the title of the honorary general of the Nepal Army, as part of a long-standing tradition, it was seen as a part of efforts from both Delhi and Kathmandu to resume dialogue after the relations turned sour.

Nepal-India relations hit a low back in November last year after the Indian government published a new political map of India showing Kalapani within its borders. Then in May, India inaugurated a road link via Lipulekh to Kailash Mansarovar in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China. In response, Nepal endorsed a new map showing Kalapani, Lipulekh and Limipiyadhura as parts of the Nepali territory.

“India was silent for a while, but now it has started showing its mettle and clout,” said Karki.

Leaders within his own party are critical of Oli’s meetings with foreign powers, especially when he faces crises.

“When it comes to foreign affairs and diplomacy, Oli is making a fool of all of us,” said a Standing Committee member of the Nepal Communist Party who did not wish to be named. “He is the one who raises a nationalistc rhetoric whenever he faces a crisis but he compromises himself with the same foreign power against which he makes his voice louder just to remain in power.”

Oli’s positive stance regarding the $500 million grant under the United States’ Millennium Challenge Corporation for two projects, rubbing shoulders with Indian security chiefs and now meeting with Chinese ambassador are some examples of how Oli is managing his ties with major powers to remain in office, said the ruling party leader.

But Oli's foreign policy adviser Rajan Bhattarai rejected the charges against the prime minister and said he has not made any mistake.

“There is no logic in criticising the prime minister as all meetings were pre-scheduled and he has not met any unnecessary people,” said Bhattarai. “If ambassadors do not or cannot fix a meeting with the prime minister, what is their use? Why should that country give them a posting here?”

But Oli’s detractors remain unconvinced with the growing foreign interest in Nepal’s internal matters.

“In a nutshell, all this is the result of our failure to remain united,” said Karki of the ruling party. “If the party remains unified and intact at a time when the opposition is weak, it is the best time to safeguard the national interest. But we have failed miserably.”

16.92°C Kathmandu

16.92°C Kathmandu