National

The rise and fall of Nepal Airlines

Once the country’s largest employer and the largest earner of foreign currency, Nepal Airlines was brought down by the two evils that plague most other public bodies in Nepal—mismanagement and corruption.

Sangam Prasain

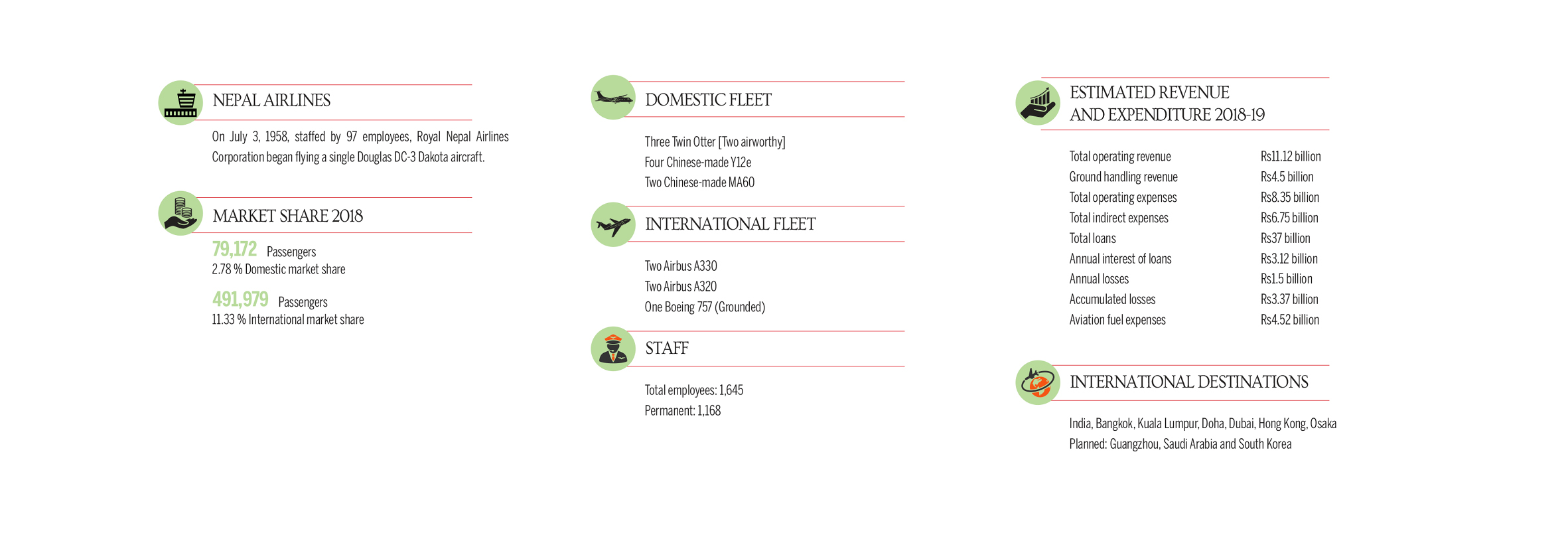

Nepal Airlines, the country’s state-owned flag carrier, is in deep financial trouble. For the first time in its 61-year history, Nepal Airlines Corporation defaulted on its interest and instalment repayment to lenders. The corporation, in its preliminary financial audit, estimates it could incur a staggering Rs1.5 billion in losses in the last fiscal year, which ended mid-July. Over the decades, the airline has not just haemorrhaged money but has also lost the public’s trust with its inefficiency.

Last November, the corporation said that it was on the verge of bankruptcy, and asked for a bailout of Rs20 billion, declaring itself crisis-ridden. This revelation came just four months after the airlines made the biggest purchase in Nepali aviation history, acquiring two Airbus A330-200s for $209.6 million. Even at that time, the corporation had become a highly leveraged company, with debt reaching critical levels—about Rs37 billion.

Last month, the Tourism Ministry formed a task force to find out what is hampering Nepal Airlines’ growth. The task force is the seventh of its kind in two decades, but almost none of the recommendations made by past task forces have ever been implemented.

The purchase of the new A330s, along with two other A320s, was meant to revitalise Nepal Airlines, but a lack of planning and a series of problems meant that those new aircraft were never put into proper operation and in full capacity.

[Read: Nepal Airlines slashes flight frequency to Japan within a week of resuming services]

“The corporation had a perfect plan to fly the new jets on long-haul routes to Europe, Australia, Japan, Saudi Arabia and South Korea,” said one former Nepal Airlines Corporation director, who asked not to be identified. “Even if it had flown to two of these routes, the two jets would have been properly utilised.”

Despite this ambitious plan to recapture the skies, Nepal’s national flag carrier remains in the doldrums. Behind the downfall of what was once the country’s largest employer and the largest earner of foreign currency are the same two evils that plague most other public bodies in Nepal—mismanagement and corruption.

The undoing of Nepal Airlines was most recently visible in its attempt to resume flights to Japan again. Within a week of operating flights to Osaka last month, the airlines had to cut its flight frequency from three times a week to two, because it had no passengers.

“On some days, there aren’t even five to six passengers,” said Ganesh Bahadur Chand, spokesperson for the corporation.

[Read: Nepal Airlines resumes its Osaka flights after a decade but it may fly almost empty]

The Airbus A330 has a capacity of 274 passengers.

Glory days

Nepal Airlines wasn’t always the last choice for passengers. In its heyday in the 1980s, it was a leading airline in the region, flying to 38 domestic and 10 international destinations. At that time, the company commanded a fleet of 19 planes, including eight Twin Otters, three Boeing 727s, and one state-of-the-art Boeing 757, purchased in September 1987. Singapore Airlines and Royal Brunei were the only other airline operating this advanced 757-200 variant at that time. A second 757 soon followed. The $110 million order for these two planes was Nepal's largest trade deal at the time.

Nepal Airlines had humble beginnings, starting on July 1, 1958 as the Royal Nepal Airline Corporation. At that time, it was obliged not only to provide aviation services but also to construct its own landing fields. On July 3, 1958, staffed by 97 employees, the new airline began flying a single Douglas DC-3 Dakota aircraft. The first towns connected Simara, Biratnagar, Pokhara, and Bhairahawa.

The government’s partner was a managing agent from India who held the minority share in the airline. Royal Nepal Airlines Corporation became its sole owner in October 1959. Three months later, it started flights to Patna, India, which connected to Delhi and Calcutta.

Seven more DC-3s were added to the fleet between 1959 and 1964. The route network was expanded internally and externally, soon reaching Dhaka in what was then East Pakistan.

With the arrival of a more advanced turboprop plane in 1966—the 40-passenger Dutch Fokker F-27 Friendship—the corporation commenced aerial sightseeing tours of five of Nepal’s eight tallest mountains. The next year, in 1971, the corporation bought a handful of Canadian DHC-6 Twin Otters—a specialised STOL (short take-off and landing) plane.

The sturdy Twin Otter was instrumental in opening up Nepal’s mountainous hinterlands, and provided a vital transportation lifeline to remote communities.

Between 1972 and 1979, the Canadian International Development Agency donated seven Twin Otters to the corporation, bringing the total number of STOL aircrafts to 12. The airline also owned a Pilatus Porter for airstrips in places above 3,ooo metres.

Supported by ticket sales and a conducive atmosphere, the airline was expanding rapidly. In 1970, the Royal Nepal Airlines Corporation invited experts from Air France to improve its management. In 1972, the airline acquired its first jetliner, a Boeing 727, in cooperation with the French carrier. Air France officials occupied most managerial positions until 1973.

According to the scant data that is available, in the 70s, Royal Nepal Airlines was carrying nearly 197,000 passengers every year. It started flying to Bangkok, marking the airline’s first foray beyond South Asia, and in 1977, it added jet service to Sri Lanka and Frankfurt, using leased Lufthansa jets for the Frankfurt route.

By 1989, passengers could fly Nepal Airlines to Colombo, Dhaka, Karachi, Dubai, Frankfurt, London, Paris, Osaka, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, Bangkok, and Bengaluru, Delhi, Kolkata, Mumbai and Patna in India. With a workforce of 2,200, the corporation was the country’s largest employer and largest earner of foreign currency. Nepal Airlines was a juggernaut and it showed no signs of stopping.

“The employees of Royal Nepal had a very privileged life. They were like zonal commissioners—powerful people during the Panchayat era,” said Tri Ratna Manandhar, former director general of the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal.

Because access to air tickets was still impossible for the general public, employees of Nepal Airlines wielded enormous influence, Manandhar said.

“The employees of Royal Nepal Airlines were known as elites because of the money, prestige and power they held. They were among the few government employees who wore ties back then,” Manandhar told the Post.

Fast forward 20 years, to 2018, and Nepal Airlines revenue had grown to only $96.5 million, producing an operating loss of $13 million. In July, when Nepal Airlines Corporation celebrated its 61st anniversary, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli mockingly said that its only achievement in the past six decades had been the accumulation of loans worth Rs36 billion.

[Read: Prime Minister Oli blasts management of Nepal Airlines for litany of failures]

“Before 1990, Nepal Airlines used to operate like a commercial airline and after 1990, it started operating like a public enterprise of the government,” said Raju Bahadur KC, who recently retired as the corporation’s director. “The past was royal. People were not attracted to government jobs but many dreamt of working for the airlines.”

What went wrong?

With the multi-party system back in force after the restoration of democracy in 1990, the lucrative airline became a haven for corruption, cronyism and nepotism. Politicians regularly interfered with the management for kickbacks and patronage. Furthermore, with the liberalisation of the Nepali economy in 1992, the domestic aviation market opened up bringing in a handful of private airlines that provided direct competition to the once-dominant corporation.

“Why did the corporation fail to grow with the same people?” said Birendra Basnet, managing director of Buddha Air, one of the private companies that has grown substantially. “Obviously, during the 1980s, the corporation had its monopoly, but now it had to compete to survive.”

Soon, economic constraints began to frustrate the corporation’s efforts to maintain enough jet aircraft in its fleet. By the late 1990s, the corporation desperately needed to modernise its aging fleet of Boeing 727s and 757s.

“It’s clear that politicians made the airline their cash cow, ruining its brand,” Madan Kharel, the executive chairman of the corporation told the Post in an interview. “You can’t blame the management because the corporation had the best management in the region at one time.”

With increasing political intervention, Nepal Airlines began to get mired in one controversy after the other.

“Our national flag carrier is a carrier of scandals,” said aviation analyst Hemant Arjyal. “The management is not solely responsible for its fall in reputation and performance; it’s the government that has brought the corporation to this level.”

One early scandal involved then prime minister Girija Prasad Koirala and Dinesh Dhamija, a British-Indian businessman. Dhamija, who had close relations with Koirala, was accused of being appointed the general sales agent of the corporation’s European operations in the early 1990s. Although Dhamija ultimately won a court battle with Nepal Airlines over these charges, the scandal tainted the airline.

In 1997, the Chase Air scam saw a loss of $783,750 from the corporation coffers, sent as advance payment based to lease a Boeing 757 that never landed in Nepal. The erstwhile UML leader Yam Lal Kandel and some board members of the corporation were accused of embezzling the money that would have been used to pay for the plane.

After the scandal, the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority recommended that all leases be conducted through a tender system. But again, in 1999, UML leader Bhim Rawal was accused of making underhanded deals in leasing an aircraft from China. Although the Public Accounts Committee recommended action against Rawal, he was ultimately never booked.

But perhaps the most infamous scandal was the Lauda Air scam, which led to Koirala stepping down as prime minister. In 2001, the Koirala-led government had leased a 12-year-old Boeing 767 from the Austria-based Lauda Air on personal negotiation, contrary to a directive issued by the parliamentary Public Accounts Committee. The government compelled the central bank to release $1 million as an advance payment to Lauda Air without confirmation from Austria. Media reports at that time had alleged that airline officials, government bureaucrats and political figures would be making a commission of $400 per flying hour, amounting to Rs160 million for the lease duration of 18 months. The government’s decision ultimately caused a loss of around Rs335 million to the corporation.

“It’s black and white,” said Basnet, the managing director of Buddha Air. “Nepal Airlines must adhere to the political agenda and the political agenda does not guarantee a profit or generate commercial interest.”

In state-owned enterprises like Nepal Airlines, Basnet said there is an “extractive political decision” where politicians make all the decisions.

“They decide which pilot will fly, which route to fly, which employee should be mobilised in which country,” he said. “They also decide which man should be given the engineering responsibility, which general sales agents should be appointed and which plane should be purchased.”

But it wasn’t just interference that brought down Nepal Airlines—mismanagement at the corporation was also rampant.

Between 2008 to 2011, the corporation was under a dual executive power system that brought constant internal conflicts in the organisation because of the strife between the two top executives, Sugat Ratna Kansakar and Kul Bahadur Limbu.

At the Dubai Air Show in November 2009, then executive chairman of Nepal Airlines, Sugat Ratna Kansakar, signed an MoU with Airbus to purchase an A330-200 and an A320. As per the agreement, the wide-body A330 and the narrow body A320 were to be delivered in two years. But after the $750,000 advance was sent to Airbus, Kansakar was jailed for financial irregularities and not following procedures.

The Commission for the Investigation Abuse of Authority, in 2010, filed a case against Kansakar at the Special Court accusing him of corruption in the Airbus purchase deal. But in 2012, the Special Court acquitted Kansakar.

The Kansakar-Limbu tussle was one of the main reasons behind the controversy of the infamous Airbus purchase deal. “Otherwise, Nepal Airlines would have at least ten aircraft on its international fleet as per the plan,” said a retired director at the corporation who did not wished to be named. It was a great loss—for the market as well as the reputation.”

By the mid 2010s, Nepal Airlines was in dire straits. The once-profitable airline had been scuppered completely. Its fleet of aircraft had reduced to two ageing Boeing 757s and two airworthy Twin Otters and it was now only flying to four international destinations. Even domestically, its market share had reduced to below five percent.

But despite its poor financial performance, it was still earning around Rs4 billion annually from ground handling at Tribhuvan International Airport. This income was the sole source keeping the corporation afloat.

New plans, new ambitions

In 2014, Nepal Airlines Corporation management decided to revitalise the ailing airline. A 10-year (2014-2024) business plan was drawn up, proposing to procure four wide-body and five narrow-body jets for use on long-haul routes to Europe, Australia and the US, besides Asia.

In a symbolic move, Nepal Airlines even changed its classic red and blue stripes livery, opting for a more modern design. This new livery was painted onto new Chinese Xian MA60 and Y12e aircraft acquired by the corporation, marking the beginning of what was supposed to be a new era for Nepal Airlines. One Y12e and the MA60 were gifts from the China but Nepal purchased the other three Y12e and a MA60 at a cost of Rs3.72 billion.

Two 17-seater Y12e aircraft and one 58-seater MA60 arrived in Kathmandu in 2014, but in a foreshadowing of what the new era would look like, they never took to the air. Nepal Airlines Corporation did not have any pilots trained to fly the Chinese aircraft and today, five years later, there are still no pilots.

The national flag carrier has six Chinese aircraft—and four of them are languishing at the airport, incurring losses in millions. The corporation says it has been scouting for captains to fly the planes, but to no avail.

In February 2015, the first of Nepal Airlines’ two new Airbus A320 jets landed in Tribhuvan International Airport. This was the first airplane procurement in 27 years. Three other planes, one A320 and two A330s, arrived one after another and joined the airlines’ skeleton fleet of two Boeing 757s.

“The arrivals of new jets rejoiced the public and the government, but the fact was that from the beginning, the corporation's roadmap did not work,” Ashok Pokhrel, a travel trade entrepreneur, told the Post.

But even before the A330s arrived, allegations of corruption were already doing the rounds. The corporation purchased the Airbus aircraft from the US-based AAR Corp for $209.6 million, the largest ever aircraft purchase deal in Nepal’s aviation history. Just a few months after receiving the two jets, the parliamentary Public Accounts Committee concluded there had been major financial irregularities in the wide-body aircraft procurement deal. The parliamentary body discovered that the procurement had caused a loss of Rs4.35 billion to the government.

“Given the past experience, it has been well established that a company cannot grow in an environment where there are controversies,” said Pokhrel.

The objective behind the purchase of the wide-body jets with a seating capacity of 274 passengers was to fly them on lucrative long-haul routes to Europe, Australia, Japan and South Korea.

“But it failed to spread its wings, because the European Commission banned Nepali airlines,” said Pokhrel, who has served as a member on the corporation’s board. “No one, not the government, the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal, or the corporation itself, was serious.”

The European Union air safety blacklist is a list of airlines that are not allowed to operate in European airspace. Inclusion on the list means that the union does not trust the authorities of a country to keep unsafe airlines from operating.

In December 2013, Nepal was placed on the blacklist by the European Commission, citing safety concerns. Being on the blacklist meant that all of Nepal’s airlines were restricted from European airspace, scuttling Nepal Airlines’ plans to operate long-haul routes.

“This was the key issue, and no one has reviewed it,” Pokhrel said. “But the Tourism Ministry thinks it is the corporation’s management problem.”

Aviation analyst Arjyal agrees that the European Union ban played a key role in limiting Nepal Airlines’ route expansion plans.

“The government seems to understand that it won’t be able to lift the ban without splitting the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal into two entities—regulator and service provider,” he said. “But I don’t know what’s stopping the government.”

Nepal Airlines’ chairman Kharel also believes the government should be doing more to help the airline, not interfere in it.

“Has the government taken the European Commission restriction seriously?” Kharel asked. “What do you expect will happen if an airline has Rs40 billion in loans but all its lucrative destinations have been restricted?”

The government has been planning to split up the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal since 2010, a vital precondition for the European Union to lift its ban. But reform is also necessary at Nepal Airlines, and at least six governmental reports have suggested various kinds of changes on different occasions.

Shankar Sharma, an economist who also served on the National Planning Commission, had submitted a report to reform Nepal Airlines nearly two decades ago, suggesting the induction of a strategic partner.

Sharma’s report had suggested selling a 51 percent stake to the strategic partner, allowing it to lead the company, while the remaining 49 percent would remain with the public. The report also recommended a second option—hand over management to a reputed foreign company.

“After the restoration of democracy in 1990, Nepal Airlines, including state-owned banks, suffered political interventions that resulted in bad management with kickbacks and patronage,” Sharma told the Post. “The corporation went through never-ending controversies, from buying planes to leasing planes and appointing sales agent to hiring pilots.”

Along with Nepal Airlines, Sharma had also suggested that the government find a management contract partner for two ailing government banks—Nepal Bank Limited and Rastriya Banijya Bank. In 2002, the government ended up hiring foreign management under the financial sector reform programme.

“Both banks saw a dramatic turnaround,” Sharma said. “But similar reforms were not implemented at Nepal Airlines.”

Subsequently, in September 2015, responding to a call from the airline, 21 foreign firms, including Lufthansa Consulting and Airbus, submitted letters of intent to provide management consultancy services. The plan was to improve its overall performance by bringing in a management consultant in the first phase and handing over management in the second phase.

.jpg)

The plan, however, failed after the Finance Ministry refused to allocate any money for consultancy services. In March 2016, the Tourism Ministry again invited requests for proposals from reputed airlines in the US, the UK, France, Germany and Australia through their respective embassies in Kathmandu to become a strategic partner with the national flag carrier.

This time, Lufthansa Consulting, an independent subsidiary of the Lufthansa Group, was the sole applicant. Lufthansa Consulting asked for a fee of Rs688.67 million, which the Tourism Ministry requested from the Ministry of Finance. But the Finance Ministry was unable to figure out whether Lufthansa’s proposal amounted to privatisation, and it decided to set up another committee to clear the confusion. The government committee in turn asked the corporation to explore 'multiple modality options’ like lease contract, strategic partner with equity, strategic alliance with foreign airlines, and management contract. The plan fell apart.

Again, in November last year, Africa’s largest carrier, Ethiopian Airlines, proposed partnering with Nepal Airlines Corporation, but just then, Nepal Airlines declared itself on the brink of financial collapse. That declaration put an end to Ethiopian’s proposal.

Kharel says the current management is doing all it can, and despite the initial failure of the Japan flights, Nepal Airlines is going to aggressively pursue more destinations.

“Despite slow results, we are on track,” Kharel said. “After Japan, we will mobilise the A330 on the Saudi Arabia route within a few months. We will also soon connect the Chinese trade hub of Guangzhou with our A320.”

Today, Nepal has more than seven million air travellers. Out of them, four million are international passengers, of which Nepal Airlines’ share is a mere 10 percent.

International airlines take home $2 billion annually from Nepal, according to Pokhrel, who is also president of the Nepal Association of Tour Operators. “Even if Nepal Airlines or Nepali carriers command 40 percent market share, they can contribute $1 billion annually to the national economy,” he said. “But someone lacks vision here.”

Many things are beyond the corporation’s control, says Kharel. In addition to political interference, many oversight bodies also interfere in the corporation’s inner workings, and then there’s the price of fuel, a bane for all airlines that fly into Nepal.

“Jet fuel in Nepal is probably the most expensive in the world. How can we earn a profit when 50 percent of our income goes to fuel?” said Kharel.

Today, Nepal Airlines has reached such lows that even a small snag could ruin the company.

“People do not trust the national flag carrier anymore,” said Arjyal. The Japan flight, which it had resumed after 12 years, was a glaring example of this.

Winning back trust and reclaiming the skies is something that will require a lot more than just ambitious plans on the paper. But given its history and its promise, some believe that the revival of Nepal Airlines is a necessity.

“Nepal is a landlocked country and the strategic importance of airlines should be realised with utmost priority,” said Sharma. “Nepal Airlines is the national flag carrier and it must be revived.”

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

22.16°C Kathmandu

22.16°C Kathmandu