National

On the verge of ‘bankruptcy’, Nepal Airlines seeks bailout

Less than four months after making the largest jet purchase in the history of Nepali aviation, Nepal Airlines Corporation, which was on a mission to reclaim its long-lost glory, said it is running out of cash and teetering on the edge of bankruptcy.

Sangam Prasain

Less than four months after making the largest jet purchase in the history of Nepali aviation, Nepal Airlines Corporation, which was on a mission to reclaim its long-lost glory, said it is running out of cash and teetering on the edge of bankruptcy.

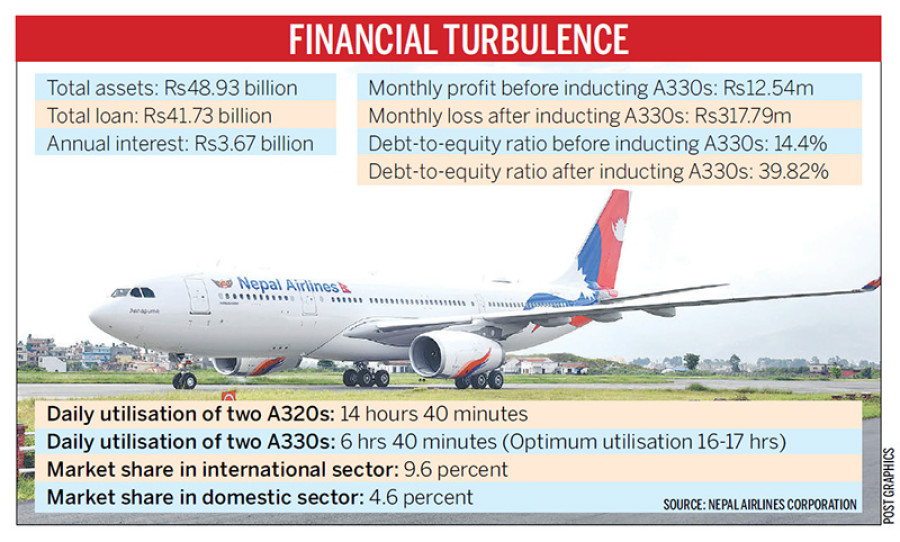

A statement made public on Thursday by the national flag carrier through a “white paper” shows that the corporation’s monthly cash deficit has reached Rs317.79 million since inducting the first of two long-range Airbus A330s into its fleet.

Before that, Nepal Airlines had a monthly revenue surplus of Rs12.54 million.

Airlines officials said the fast depleting cash flows are even more worrying.

“We are facing severe financial stress and have requested the government to bail us out,” said Madan Kharel, executive chairman of the corporation. “The reason we have been dragged into financial stress is that we have not been able to operate the newly acquired A330s to their full capacity.”

Kharel said although the situation may improve once the whole fleet is in operation, the corporation desperately—and urgently—needs a bailout from the government.

Since summer, Nepal Airlines’ debt-to-equity ratio, which measures the financial health of a company, has swelled to 39.82 percent from 14.40 percent. A higher ratio indicates the company is receiving most of its financing from borrowing, threatening bankruptcy if business continues to decline.

According to the white paper data, revenue earnings from the two wide-body jets from August 1 to September 15 stood at Rs264.8 million, while the expenses nearly tripled to Rs756.6 million, in addition to a staggering deficit of Rs491.8 million.

At the moment, the two A330 jets are being utilised for less than seven hours daily, less than half of the required flight time to generate a decent profit.

The revelation about the dire state of Nepal Airlines’ finances comes on top of the corporation’s massive loans to various institutions—its long- and short-term loans stand at Rs41.73 billion and it owes more than Rs3.66 billion in interest annually.

“The corporation’s financial health is really bad,” an official familiar with the corporation’s operations told the Post. “If things continue the way they are, the airlines will begin defaulting on payments and staff salaries.”

Although many carriers in the region, including some big players in India, are hurt financially because of soaring aviation fuel prices and the rising dollar, the case of Nepal Airlines is different. “The new planes have not been utilised prudently and commercially,” the official said.

The national flag carrier, instead of scoping pilots for the new aircraft, followed its traditional practice—to get the planes first and find the pilots to fly them later. It still has at least three planes sitting on the tarmac at the Tribhuvan International Airport while it frantically looks for capable pilots. It was indeed a gargantuan project to equip the airlines with the youngest fleet in the country—inducting two Airbus A320 aircraft in 2015 and two additional wide-body A330 in 2018.

The induction of four jets had been described as a game-changer for the corporation—and the country, allowing the airlines to compete with other international players on long-haul routes to Europe, Japan and the Middle East. However, some airlines officials say the corporation did not plan its operations efficiently.

“Despite the pilot shortage, the corporation again started homework to procure two more A320neo jets for international route and six Viking Twin Otters for domestic operation,” said a senior captain at the corporation who asked not to be named. The plan, however, did not move ahead due to an abrupt change in management.

Kharel admitted that the new planes were unable to fly to their optimum because of a shortage of flight crew. “We were also not able to expand our routes to Japan, South Korea and some European countries from where we would have generated good income,” he said.

17.78°C Kathmandu

17.78°C Kathmandu