Money

A grieving father’s quest to expose negligence behind Nepal’s deadliest air crashes

After losing his daughter, grandson, and son-in-law in the 2024 Saurya Airlines crash, Prakash Khatiwada’s relentless campaign for justice continues.

Sangam Prasain

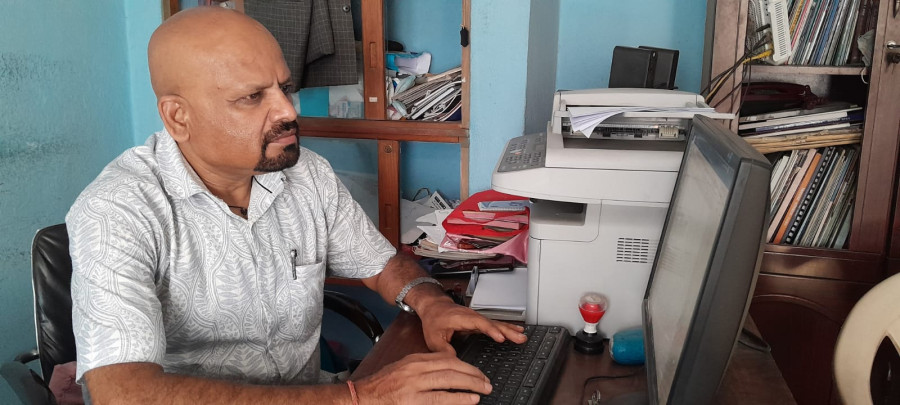

For the past one year, Prakash Khatiwada has lived with a single purpose. A former journalist, he has made it his duty to knock on the doors of government officials, ministers, speakers, lawmakers, and even a former president, pleading for justice.

Khatiwada runs his own YouTube channel, where he collects every bit of news, every report, and every publication on aviation disasters in Nepal. He studies them, breaks them down, and analyses the causes.

Yet, despite all the hours of research, he has not found the answers that haunt him: Why do air crashes happen in Nepal so often, and why are they treated as if they are only accidents?

When the government abruptly froze social media on September 4, Khatiwada refused to let the silence bury his campaign. He created a Viber group called ‘Struggle for Justice’ and quickly added 101 participants. At the same time, he continued sending personal messages to all 330 federal lawmakers [now former] in Nepal, reminding them of their duty and asking for accountability.

Khatiwada’s determination stems from an unbearable tragedy.

On July 24, 2024, he lost his daughter, son-in-law, and four-year-old grandson in the Saurya Air crash at Kathmandu airport. The CRJ-200 aircraft, operated by Saurya Airlines and registered as 9N-AME, had taken off from Tribhuvan International Airport for a ferry flight to Pokhara for heavy maintenance. Seconds later, it crashed. Of the 18 people on board, only the captain survived.

“No matter how long it takes, I will fight for justice,” Khatiwada says, his voice firm but weary from grief. He has told his story in countless media houses. “Some admire my struggle, but many dismiss it. They think it’s hopeless. But I cannot let this go.”

Still traumatised, Khatiwada refuses to give up. To him, the July 2024 disaster was not an accident—it was a “mass murder”.

He points out how quickly the tragedy was forgotten once families were compensated by insurance payouts. “Most people accepted the money and moved on. But I can’t. My fight is not about money. It is about justice.”

Khatiwada’s persistence, echoed by public outrage over a series of fatal crashes, has begun to make waves.

On August 20, the now-defunct parliamentary International Relations and Tourism Committee ordered the government to form a high-level judicial committee to investigate aviation disasters of the past five years.

The committee’s decision bluntly acknowledged the cracks in Nepal’s aviation system.

Past accidents and incidents have shown that shortcomings in Nepal’s aviation regulatory system, human resources, as well as management, along with negligence, have made Nepali skies unsafe and air travel risky, according to the committee decision.

“To stop more accidents, we direct the government to study and analyse all accidents of the last five years, identify the guilty, and recommend action.”

Raj Kishore Yadav, former chairperson of the parliamentary committee, went even further. “The crash of Saurya and a few others is not just an accident. It’s a mass murder. The guilty should be prosecuted. The government’s fact-finding reports are limited—they cannot punish anyone. That is why we need a judicial inquiry.”

This is uncharted territory for Nepal. Despite 71 years of aviation history and 109 accidents, no crash has ever triggered a judicial or criminal investigation.

Previously, in October 2023, the government had formed a high-level study committee chaired by former Supreme Court Justice Anil Kumar Sinha (now a minister in the interim government) to review the aviation sector.

But that committee, too, lacked the mandate for judicial accountability.

For the first time, lawmakers of the now dissolved House pitched for a panel headed by a former Supreme Court justice and aviation experts to recommend criminal responsibility where negligence is found.

Officials at the Ministry of Tourism and Civil Aviation say they are in discussions with the law ministry and the Office of the Attorney General to determine how a judicial inquiry could be structured.

“The ministry usually conducts fact-finding investigations, but a judicial inquiry is different,” said one official. “We are waiting for legal advice.”

In other countries, such dual-track systems are standard. In France, every crash is examined both by a judicial investigation led by prosecutors and by a safety investigation conducted by the Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses (BEA).

While the judicial side focuses on liability and potential criminal charges, the BEA aims to improve aviation safety. Both run independently but cooperate, sharing evidence such as flight recorders. The United States follows a similar pattern, with safety probes led by the National Transportation Safety Board, but without restricting prosecutors from filing criminal charges when negligence is involved.

Nepal, however, has relied solely on fact-finding reports prepared under ICAO Annex 13, which emphasise safety improvements but do not apportion blame.

The official investigation report of the Saurya crash, released in July 2025, revealed disturbing negligence. Cargo was never verified or properly weighed. Dangerous goods were loaded without permits. Maintenance equipment was stored in the cabin. Safety checks were ignored, and non-essential personnel were allowed onboard.

The report painted a portrait of Saurya Airlines as an institution where safety manuals were disregarded, oversight was lax, and risky practices became routine.

The Yeti Airlines crash of January 2023, which killed all 72 passengers, told a similar story.

Regulators approved flights to Pokhara’s new airport hastily, without ensuring that proper procedures or validation flights were in place. The Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal (CAAN) failed to develop or approve necessary operating procedures.

For Khatiwada, these failures confirm his suspicions.

“The company listed my four-year-old grandson as staff. They made my daughter an employee of Saurya Airlines. The entire operation was illegal,” he says, carrying with him translated copies of the investigation report, letters proving his daughter’s employment with the energy ministry, and photographs of his lost family. “The company manipulated records to protect its business and tarnish my family’s dignity.”

He argues that the crash investigation team itself was illegally formed, as many members did not meet the qualifications to serve.

After back-to-back disasters in 2023 and 2024, lawmakers have been demanding accountability from not only the airlines but also the Civil Aviation Authority of Nepal, which is accused of gross negligence.

If a judicial inquiry is launched, it could hold airlines, regulators, manufacturers, pilots, and engineers criminally responsible for misconduct leading to loss of life.

But Nepal lacks specific laws to prosecute such cases. While the Civil Aviation Act refers to judicial proceedings, no mechanism exists to enforce them. Even if an independent commission recommended cancelling an airline’s licence, there is confusion over which authority would implement it.

The ICAO Annex 13 framework, which Nepal follows, is explicit: accident investigations are for prevention, not blame. Any judicial proceedings must be separate. Yet Nepal has never taken that step.

Still, there are signs of change.

In July, the Kathmandu District Court issued a landmark verdict against the Dhaka-based US-Bangla Airlines over the 2018 crash of Flight 211, which killed 51 people. The court ordered the airline to pay Rs378.6 million in compensation to families, beyond the standard $20,000 insurance payout.

This was the first time in Nepal’s history that an airline was held liable for gross negligence.

“It’s our sovereign right to file a case against any misconduct,” says lawyer Amrit Kharel, who represented several victims’ families. “If negligence kills, there must be accountability. Investigations cannot just end with technical reports.”

The precedent means families of crash victims can now sue airlines in Nepal for unlimited liability in cases of misconduct.

For Khatiwada, this is a ray of hope.

But again, the country has been in chaos in the past couple of weeks. Nepal’s President Ramchandra Paudel dissolved the House of Representatives at the recommendation of newly appointed prime minister of the interim government, Sushila Karki. The House was dissolved with effect from 11 pm on September 12, 2025, according to a notice issued by the President's Office.

The President has also fixed March 5, 2026, as the date for holding fresh parliamentary elections. Khatiwada still thinks things will come back to track again, sooner or later.

Nepal’s aviation industry has grown rapidly since its humble beginnings in 1953, when flights started with three old DC-3 Dakotas. Passenger traffic has surged from one million to 10 million in just two decades. Yet, the skies remain unsafe. In 70 years, more than 70 crashes have claimed nearly 1,000 lives, most due to negligence.

Khatiwada carries his grief every day, but his fight for justice remains undiminished.

“I will keep fighting,” he says. “My daughter, my grandson, my son-in-law—they were not victims of an accident. They were victims of negligence. And negligence must be punished.”

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu