Miscellaneous

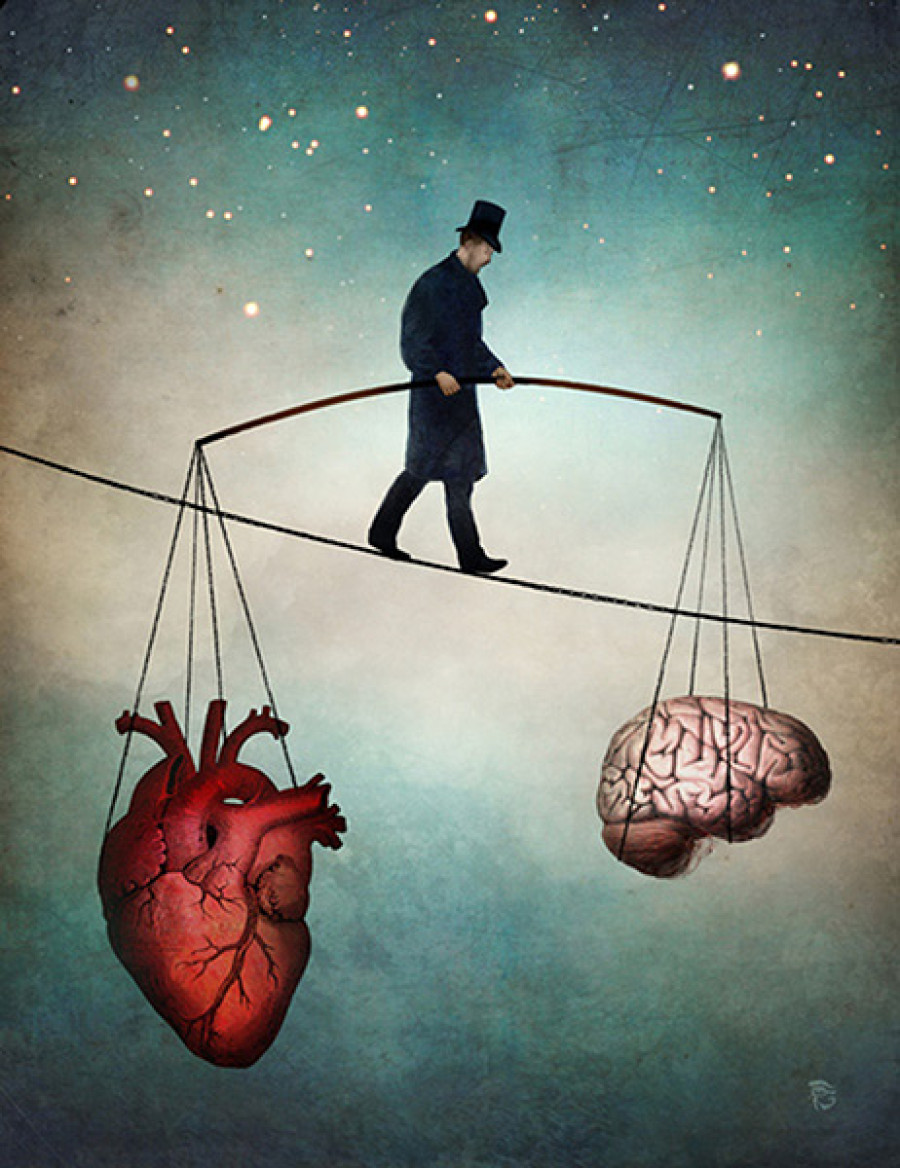

Head over heart

No matter how much we deny or conceal it, emotions play an important and omnipresent role in world politics. The most obvious example would be the inherent emotional nature of global terrorism.

Avasna Pandey

No matter how much we deny or conceal it, emotions play an important and omnipresent role in world politics. The most obvious example would be the inherent emotional nature of global terrorism. Consider the images of the terrorist attacks of September 11, Baghdad car bombs in 2007, or be it recent attacks in Brussels, Dortmund, Manchester or London—they all have a decisively emotional impact on how people discern issues of security and national identity. The motives of terrorists are also presented in emotional terms, such as “irrational”, “evil”, or “fanatical” and the reactions to these attacks are equally emotional as well. Further, emotional appeals, such as nationalist rhetoric are often used by politicians to win support for their positions. In the same vein, politicians have often used fear to manipulate people and serve their own vested interests. But fear and hatred aren’t the only emotions that play a telling role in world politics—they represent just one side of the emotional spectrum. Empathy and compassion are just as influential. And while emotions are central to numerous aspects of world politics, it has surprisingly received scant attention during analysis of events.

Neta C Crawford in her paper titled The Passion of World Politics (2000) writes that emotions are everywhere in world politics— from (mis) use of fear to the necessity of goodwill and empathy in peace settlement negotiations. She even stresses the point that “emotion is implicit and ubiquitous, but under theorised”. But why is that that despite it being present everywhere the study of politics as a discipline has always kept emotions at an arm’s length? For this, much has to do with the way we study politics and international relations itself. Clearly, there is a hierarchy in theories wherein, thanks to events during the Cold War, Realism emerged as triumphant. Issues and events are more often than not looked at from a positivist, objective outlook which consequently forecloses any agency. Because emotions cannot be “empirically tested”, they are not granted a place in the production of knowledge about world politics. They are also thought to be merely ephemeral. As a result, decision making has emphasised cognition over emotions.

In international relations, role of emotions have been most widely acknowledged in foreign policy. Perhaps that is why a person’s “temperament” is one of the most sought after characters in leaders as it can predispose them to react to a situation in a certain way. This explains why the presidential debates in the United States in 2016—as other countries in the past—placed such importance on the candidates’ temperament. Donald Trump, whose temperament and likeability were so vehemently debated before the elections, is now the US president and has tried to introduce divisive policies like the ‘travel ban’ from select Muslim-majority countries and building a wall along the southern Mexican border. These decisions, it can be argued, stem from Trump’s (and by extension his voter base’s) deep rooted xenophobia, hence making a case for emotion’s impact in political decision making.

Same can be said about the EU referendum in the UK that resulted in Brexit. The emotional politics at the centre of the referendum—the idea of reclaiming the British economy and a control of its borders—was perhaps an appeal to the gut, and the heart, rather than calculated decisions about the consequences. Closer to home in India, ever since the BJP stormed into power, religion has been central to much of the rhetoric. Religion is something deeply personal to individuals and nothing stirs emotions more than the mixing of religion and politics. The partition of India and the formation of Pakistan on the basis of a two-nation theory is an example that instantly comes to mind. In recent times, the Modi government has mobilised masses and organised campaigns solely on the basis of religion. Pushing a nationalism that derives its roots in rhetoric of Hinduism, an inclination towards religious demagoguery of the Indian Prime Min-ister is now becoming increasing evident.

Here, in Nepal as well, politics has not been bereft of emotions. The People’s War waged by the Maoist, for instance, echoed notions of equality, inclusion and identity among others, which again, touched upon emotional chords. Leaders made several emotional appeals, rather than of reasoning and rationality with citizens to join their movement. You don’t have to look too hard; there are enough instances that lay bare the frequent use of emotions in politics. But cynicism is easy; what is important to recognise is that negative emotions are not the only emotions of the human experience. If used tactfully, positive emotions too can be equally powerful, if a tad bit harder to conjure up.

With so many terrorist attacks around the world, war and conflict flaring in numerous places, widespread poverty blighting our lives, maybe it is time we let our emotions surface. Some kind of tragedy is unfolding almost every day somewhere. In such situation, would it be prudent to be a bit more passionate as we are strategic? Could we reproject sensitivity not as a bane, but rather a blessing? News of the use of chemical weapons in Syria, kidnapping and rape of innocent girls in Nigeria, increasing disparity between rich and poor, degradation of the environment—these should outrage us as well. But, they have become so common that now we, in some ways, have become desensitised. We eagerly switch channels, or readily turn pages of a newspaper when encountering such news. Why is it harder to be moved by compassion than it is by fear?

It’s not too late. World politics and international relations have too long been driven by power politics and zero sum games. Perhaps it is time we pour in our hearts and not just apply our minds when trying to come up with solutions to the problems that blight us. Sure, rationality and logic is required but maybe it is time we stopped being guided by it alone. Compassion and empathy are just as important. Only when we stop seeking give-and-take relations and strategic alliances and give humanity a chance, can we envision a better future. And it’s high time we make that change.

- Pandey is a recent International Relations graduate from Jawaharlal Nehru University

13.54°C Kathmandu

13.54°C Kathmandu