Books

Finding warmth in the Canadian winter

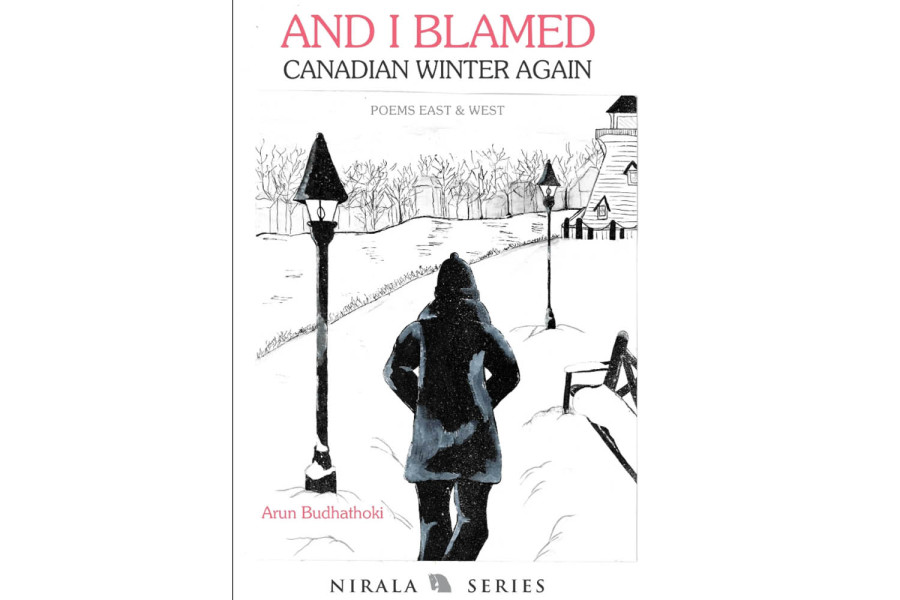

In ‘And I Blamed Canadian Winter Again’, Arun Budhathoki explores divided selves, diasporic longing, and fleeting moments of hope.

Haris Adhikari

We are often trapped in our multiple, warring selves. Which one should we choose? Which is more authentic? Acceptable? More beautiful? Or more divine? These are some of the conundrums that many of us inwardly wrestle with.

In his third poetry collection, ‘And I Blamed Canadian Winter Again’, Nepal-born poet Arun Budhathoki, now living in Canada, also confesses to being “constantly haunted by self-doubt” when transforming strong emotions of his diasporic life into poetry. However, he surpasses his “infirmities” when inspired by his poetic muses. This is all evident in the book, which presents dreamlike visions of transcultural existentiality and features unique flavours in place-and memory-based poetry, emphasising contemporary Western and Eastern urban life.

The book houses forty-six poems in five sections—all subtitled with city names: Fredericton, Kathmandu, Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto. Interestingly, what the book’s title purports to the eye eventually reads only like a seasonal recurrence, or appendage-like—that is, there is a lot more in the book. Apart from themes such as the coldness of megacities, alienation, loss, divided selves, and existential gloom, the book also explores heartening moments within urban spectacles, along with themes such as intercultural exploration, hope, human connection, love, and poetry as a form of salvation. This said, Budhathoki’s poems touch the human heart in many ways, mostly through monologic and photographic style, strange images, poetics of ‘in-transit’ life, and lunatic self-search.

What I particularly appreciate about his poetics is his profound valuing of the voice of the inner soul and the importance of living deeply, as seen in many of his poems, including ‘Visiting the Therapist’, where he depicts a frustrated student who shows the counsellor his “imaginative passport/ with valid visas/ to exercise madness.” Unlike in some eclectically liberal academic spaces, most universities’ disciplinary boundaries still do not entertain creative urges for experimentations, and this is precisely what the persona dislikes, speaking of his track record in creative academic inquiries. Yet this, away from hierarchical/ institutional whims, also concerns making an informed decision right in the beginning. However, there is no denying that doing something of passion or creative experiments in one’s studies involves deep living and can be rewarding in several ways. Interestingly, the poem also suggests other layers of meaning, such as the mindset affected by sudden changes in the policies for immigrants.

The idea of living deeply, however, does not help much when one’s soul is being lacerated by sociocultural and structural biases. This is what the poet expresses powerfully in ‘I Hate Beer Bottles’. His subsequent observations show that life in Canada is far from what he initially thought. Policies changed. His plans were disrupted. His dreams were thwarted. And he felt like a puppet in the hands of evil pharaohs. Compared to Nepal, however, Canada feels better. The poet admires Nepal’s cultural beauty and spiritual places, but also shows Kathmandu as a city weighed down by crime, corruption, chaos, pollution, narrow thinking, and suffocation. So, while searching for self and identity in the alien land, he sings of his madness, or demands that he get to sing it. Nevertheless, joy-and-peace-bestowing moments and muses, including fruits of hard work and patience, also abound and await him in this land in different forms.

His sources of renewal, peace, and musings often involve walking in cities, hiking, visiting museums, connecting with friends and family, and listening to poetry and music. For example, his poem ‘The Return’ takes him to a jungle, away from the snow-heavy Fredericton, where “…rarely any souls were to be seen.” This ‘return’, through the deep dark of the jungle that reminds the poet of “two dearest souls” who left this world too early, helps him return to himself and claim the emotional “writer” within, shedding off the “skin” outside. Interestingly, the surface does not interest him; yet it goes deep into his interiority.

At other moments, the poet’s persona is completely ‘dissolved’ or ‘absent’, as in “Crossing Victoria Street.” This poem economically sketches a sensual city spectacle in which the persona is lost in “the last spring”—his sweet love who is oceans away. Similarly, the heart-rending disappearance of Jerusha Rai, the indigenous Nepali singer whom the poet had met and befriended in London, finds a poignant expression in ‘Mourning Jerusha’s Disappearance’. Such moments show that purity of heart and soul and emotional depth is all he is after, and this could be the reason why in this book he mostly sings of how the cities and city life touched him rather than describe the cityscapes in greater poetic detail. This is, however, all fine in cases of his odes, because that’s the nature of odes.

But the poet demonstrates a remarkable knack for discerning subtle cues embedded in urban landscapes. For a person who is new to a place, ‘sense of place’ is a very difficult thing to capture.

But the poet, even with his limited assimilation, amazes the reader when he paints layered moments and meanings that go deep into both himself and the places that inspire him to write.

Such moments sometimes offer wise lessons to follow. For example, the Wolastoq valley in the poem ‘A Visit to Fredericton’ mocks the poet for his “infirmities” but the poet, while captivated by the valley’s heavenly beauty, simply chuckles, realising that “perfection was attained”. Here, the eventual poetic catch is that ‘constantly building a sense of understanding is perfection’—a truth even more vital in intercultural settings. And who knows it better than the poet himself, who has come through “uninterrupted travels”.

The in-transit life, as the poet suggests, is also synonymous with fleeting truths of life, like “the mindless winds” in Fredericton, which he romantically likens to a feel of “Valentine’s Day”. Similarly, when “the sleek roads of Montreal” appear to invite him to go for an eternal reaching after joy, he is untouched by this, feeling like an intoxicated “butterfly” who is happy to dissolve in the surrounding colours. Why fly? Why run? Why not dissolve in what appears to be a dream? The poet says. Indeed, stasis is also meaningful sometimes, or in certain phases of life. And it is interesting to note that sometimes the poet even celebrates loneliness, for it ironically bestows upon him a sense of peace.

There are also bittersweet ‘in-transit’ moments. For example, he invites the reader into a regretful mind when he says he “never bid a proper goodbye/ to anyone.” But he does value and cherish warm and soulful connections. Nevertheless, he is burdened with his own inability to make soulful connections in this alien land. For example, “a bizarre painting” in Fredericton’s Capital Complex is something that runs to the point he thinks: “a bear or an alien” walking with “a human.” Similarly, while grateful for everything that satisfies his soul or aesthetic sensibilities, he still longs for the smiling faces of Nepali people—faces he misses on the footways of Canadian cities. This longing, however, finds some relief when he encounters or visits fellow South Asian immigrants. In moments of illness or emotional lows, he, however, feels helpless and is haunted by life’s fragile thinness or its eternal in-transit-ness. Yet paradoxically, this cleanses his soul. Through such lunatically empowered mental states, he takes the reader—sometimes even defying the boundaries of language—toward strange streaks of light that await him on the other side of existential gloom or melancholy. In such moments, his poetic madness becomes his medicine.

Overall, the collection is engaging and thought-provoking. But I offer a caveat to readers: to truly relish Budhathoki’s poetry, one must be willing to plunge into both Plathian and Bukowskian modes of expression. Along the way, the reader also encounters a refreshing newness in his poetic craft and vision. More importantly, he surprises the reader by poetically celebrating a variety of qualia associated with the in-transit life, leaving behind a unique trail that illuminates how (cosmopolitan) places and spaces shape a creative soul.

_______

And I Blamed Canadian Winter Again

Author: Arun Budhathoki

Publisher: Nirala Publications

Year: 2025

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu