Books

Madan Puraskar: Its significance and criticisms it often receives

One of Nepal’s eminent book awards has played a very important role in promoting Nepali literature. It, however, has not been free of criticism.

Srizu Bajracharya

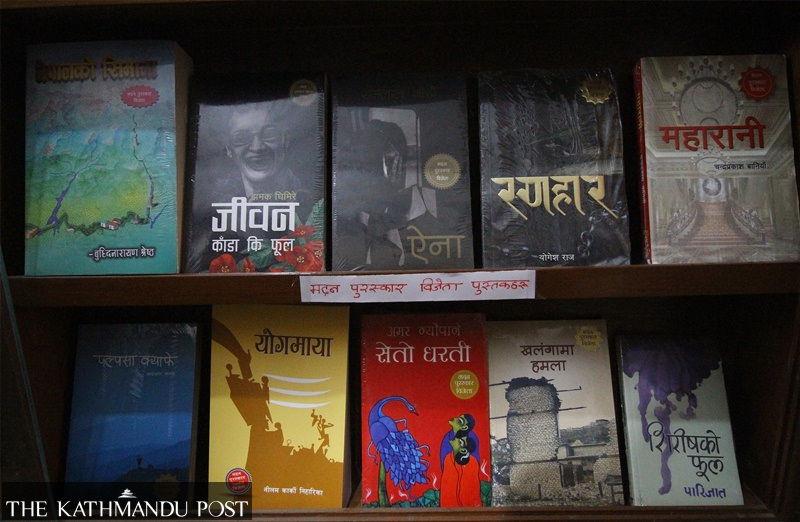

In 2016, when Ram Lal Joshi's self-published fiction book 'Aina' was awarded the Madan Puraskar, Nepal’s most respected Nepali book award, Joshi's life changed overnight.

Before the award, very few knew about Joshi, a resident of Dhangadhi, and his work. After winning the award, Joshi's book started flying off the shelf, and he found himself swarmed with calls from publishers wanting to reprint ‘Aina’.

“I used to think a writer from nowhere and with no connections whatsoever had no chance of winning the country’s most prestigious literary award. I was wrong,” says Joshi. “The recognition renewed my sense of responsibility as a writer. It also made those of us from semi-urban and rural Nepal realise that we are as capable as those from Kathmandu.”

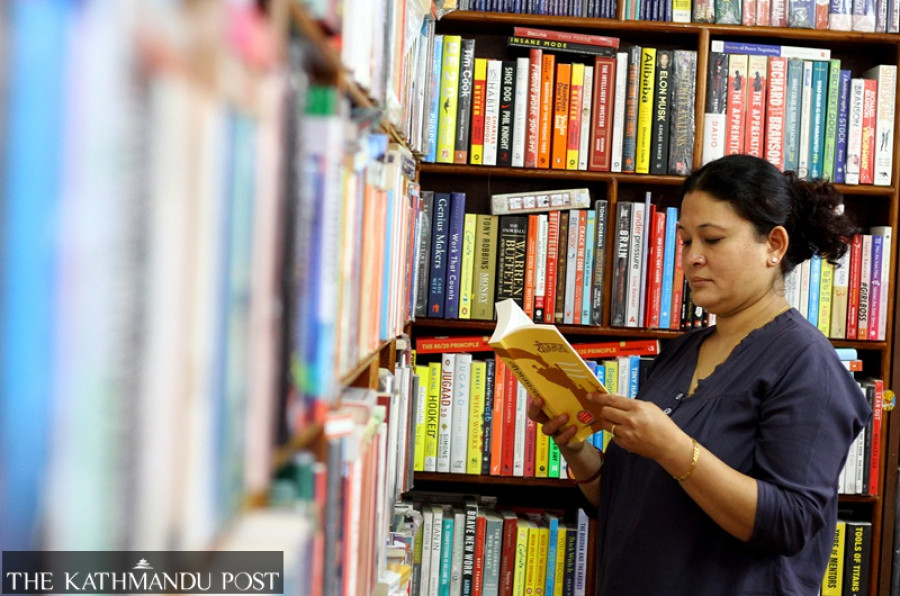

A month ago, when Madan Puraskar Guthi released this year’s shortlisted books, the list featured Jason Kunwar’s ‘Ramite’. Within a week of the announcement, Sunil Maharjan, manager of Patan Book Shop, sold over 50 copies of ‘Ramite’.

“Before 'Ramite' got shortlisted, nobody came to our shop asking for the book," says Maharjan. “The demand for the book after the announcement is a testament to the influence the award holds."

Ever since Madan Puraskar was first given 65 years ago, the award has played a very important role in promoting Nepali literature, but the award, which Madan Puraskar Guthi manages, has not been without criticism. It has become an annual routine for the award to court criticism for lack of transparency and fairness.

Madan Puraskar was the brainchild of Kamal Mani Dixit, an ambitious Nepali littérateur. He set up the award with a vision to promote Nepali literature, recognise exemplary works in Nepali literature, and to encourage people to write and publish books, says Kunda Dixit, the editor and publisher of Nepali Times and one of the sons of Kamal Mani Dixit.

“But even before he set up the award, he established Jagadamba Press," says Kunda.

But when the senior Dixit realised that just setting up a press wasn’t going to do much to promote Nepali literature, he decided to start Madan Puraskar, says Kunda.

The award then went on to be established under the memory of late General Madan Shumsher Rana, husband to Jagadamba Kumari Devi for whom Kunda's father and grandfather worked at the time. Devi was known for her philanthropic works and for supporting educational institutions.

Neelam Karki Niharika, who won the award in 2018 for her fiction work ‘Yogmaya’, agrees that the award is still held in very high regard and receiving it changes writers' lives.

“One of the biggest challenges writers in Nepal face is not being able to focus solely on writing. But I have seen many winners of the award being able to dedicate themselves just to writing,” says Niharika. “The award not only gives writers recognition but also helps them create conditions in which they can write freely.”

Despite being regarded so highly by writers, Madan Puraskar continues to receive its share of criticism. For years, many within Nepal’s literary circle and beyond have questioned the credibility of the selection process. Some have even accused the award of being biased.

One of the most ardent critics of the award is writer Shivani Singh Tharu, known for her political thriller, ‘Kathmanduma Ek Din’.

“I find it highly problematic that the award does not make public its jury members and selection processes. It does not even give any explanation for awarding a particular book,” says Tharu. “I even once wrote on Twitter saying that it’s almost like they announce winners from their pockets.”

Tharu has for years called for the guthi to reveal the identities of jury members and make public the criteria for choosing winners.

“When people know who the jurors are, people will be able to decide if they want to send their work or not. That would be fairer,” says Tharu. “Kunda Dixit and Kanak Mani Dixit, the two main people behind the Guthi, have always stood up for transparency and fairness. But given the secrecy around the award their family started, I feel they are not very sincere towards their own beliefs.”

Writer Narayan Dhakal, one of the former jury members of Padmashree Sahitya Puraskar (a literary award), also believes that award organisers should always make public the jury members, to maintain objectivity.

“When you make public the names of the judges, it gives credibility. It also makes the judges accountable to their decisions. Transparency also allows for people to see if there has been a diverse representation among judges,” says Dhakal.

Another criticism that many have made against the award has to do with its submission process. Writers and publishers have to self-nominate their works, and many critics say that in itself is problematic.

“The current submission process has made the work of the Madan Puraskar Guthi easier. But I think it’s the organiser’s responsibility to do the research and nominate books instead of asking writers and publishers to submit their works,” says Dhakal.

This year, one of the criticisms of the award revolves around Kumar Nagarkoti’s ‘Kalpa Grantha’ getting shortlisted.

“When the book was nominated, it was not even available in the market,” says Tharu. “All these issues just goes on to show why the award needs more transparency.”

According to Tharu, many Nepali writers are unsatisfied with the way the award is given, but many opt to stay silent because of the power the award holds, and the writers’ own aspiration of someday receiving the award.

“I also once had hopes of getting this award," says Tharu.

But unfazed by criticisms, people associated with the Madan Puraskar Guthi say that the guthi has always been fair and discreet with its decisions.

“Many do not know the screening, assessment, and selection process of the award and that's why we get a lot of criticism,” says Deepak Aryal, a board member of the Madan Puraskar Guthi. “For an outsider, it might appear that it’s the Dixits who are calling the shots, but that is not the case."

According to Aryal, every two years, the guthi appoints a committee to review submitted books. And they make sure that even the identities of the committee members are not revealed even amongst each other. He adds that the committee is usually made of at least seven members, and each member picks ten books from the year’s submissions.

Depending on the kinds of books selected, the guthi sets up another committee of qualified people to judge and review the books that the first committee forwards. The second committee’s role is to shortlist the year’s best works and then decide the winner.

“At times when the second committee members fail to reach a mutual consensus while coming up with the shortlist, the books are eliminated by default. Alongside these two committees, the guthi also appoints an alternative committee of readers and experts to crosscheck the shortlist,” says Aryal. “Then there are also general members, who are the board members of the guthi. If the second committee members cannot come up with the winner, only then do general members step in.”

The process is rigorous, he assures.

Addressing this year’s criticism regarding Nagarkoti’s works, Aryal says, “The guthi makes sure that the books submitted are available in the market, and at the time of reviewing nominated books, Nagarkoti’s book was available in the market. As for the criticism of the guthi’s submission process, we do not have the mechanism to go through each and every book published in the country and that is why we ask writers and publishers to self nominate. If and when we do have such a mechanism in place, we will make changes to the submission process.”

Kunda, who’s regarded by many as the face of the award, is not perturbed by the relentless criticism the award continues to receive every year.

“Contentions are just discussions. And that happens everywhere,” says Kunda. “But you also have to understand that every institution has its own rules and practices that are put in place to ensure they align with the organisation’s goals. Some make jury members public, others don't. We feel discretion is needed to maintain objectivity and avoid unnecessary interference in the selection process.”

“We have a small community [of intellectuals], and when everyone knows everyone, think about the pressure a jury member would be subjected to,” he adds. “We have in the past offered a citation for the prize-winning book for its contribution to Nepali literature; we could resume doing that if board members feel the need.”

For 65-year-old Bhagiraj Ingnam, the criticism around the award is the last thing on his mind. His book 'Limbuwan’s Historical Document Collection' was announced the winner of this year's Madan Puraskar.

"I am elated that my book has been awarded Madan Puraskar. I worked extremely hard for the book and the research work I have done for it is something that the Limbuwan community and organisations should have done a long time ago," says Ingnam. "I am sure the recognition will help me reach more readers."

There is no doubt that Madan Puraskar is one of the most celebrated book awards in the country, say Joshi and Karki.

“It would certainly be nice if the guthi could address some of the issues people are raising,” says Joshi.

Karki who interviewed the late Kamal Mani Dixit some years ago to address the criticisms of the award says she wants to believe that the award is fair. “It’s not just because I won the award. But because I can see their effort in establishing eminent works of Nepali literature,” says Karki.

“Everyone has their own opinion of which book should win, so it is impossible to have a perfect vote for any work. Some great authors do not get awarded. You see, recognitions are there to keep the industry moving forward,” says Karki. “And awards like Madan Puraskar become monumental because they inspire and motivate people to do more. For people, that kind of honour changes everything. It keeps us going.”

20.9°C Kathmandu

20.9°C Kathmandu