Books

Books, belief, and the birth of a theory

Drawing from literature and ancient Eastern texts like the ‘Natyashastra’, Nirmala Mani Adhikary challenges the Western dominance in communication theory.

Sanskriti Pokharel

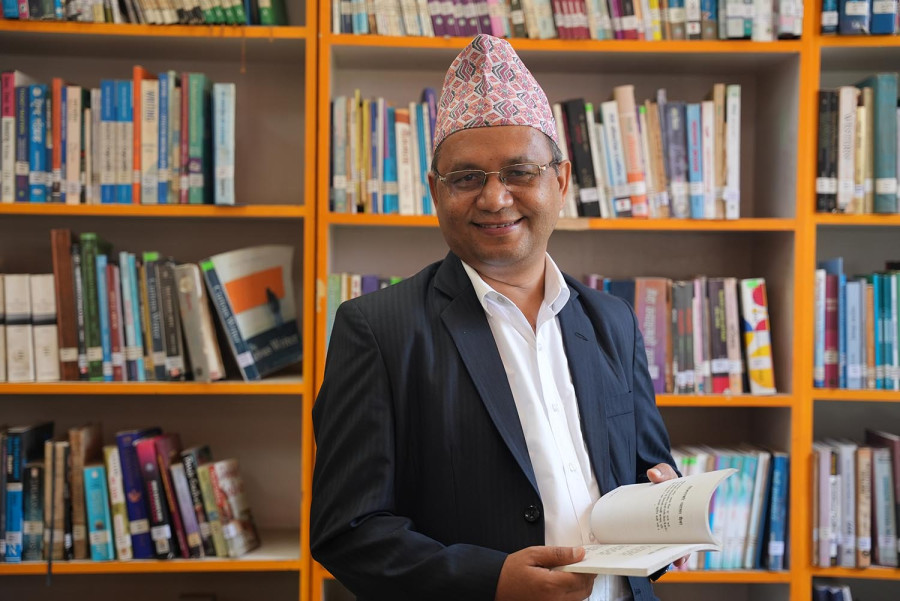

Nirmala Mani Adhikary is an author and communication theorist known for developing the Sadharanikaran Model of Communication and the Sancharyoga theory.

Adhikary is a professor and the head of the department of languages and mass communication at the School of Arts at Kathmandu University. He is also the Chairperson of the Media Studies Subject Committee and the Chief Editor of Bodhi: An Interdisciplinary Journal.

Moreover, he is the author and editor of more than 60 published books, including ‘Theory and Practice of Communication—Bharata Muni’ (2014) and ‘Sanchar Siddhantikaran’ (Communication Theorization—2019). As many as 80 research articles written by him have been published in journals and anthologies worldwide.

The Post’s Sanskriti Pokharel sat down with Adhikary and discussed his biggest intellectual influences, journalism, and ancient texts.

From being a district correspondent to Chief Editor and now a theorist, how has your view on the power of media changed over time?

Starting as a district correspondent at Dainik Janamat in 1995, then writing for Ghatana ra Bichar in 2000, and ultimately becoming the Chief Editor of Insec Online in 2004, my understanding of the power of media has developed over time.

When I first entered the field, the media felt like a natural extension of my voice. I loved poetry and actively took part in literary events and essay competitions. Editors noticed my writing and encouraged me to pursue journalism, with the added incentive of payment, unlike poetry. That paved the way for me.

As my work was published and I gained recognition, I understood the media’s influential role. I initially viewed the media as a platform for self-expression, a belief I still hold internally. However, my perspective has evolved. Over time, I’ve noticed that social and political factors often overshadow the media’s influence. Currently, I perceive power as dynamic, with various forces taking precedence based on the situation.

Who are your biggest intellectual influences, inside or outside Nepal?

Some of my greatest intellectual influences are people I met in person, while others inspired me through their writings. My father was a lifelong learner. Despite living in Tanahun, intellectuals from Kathmandu, Damauli, and Pokhara would come to seek his insights. Watching him fluently quote verses and texts left a lasting impression on me and sparked my desire to become a scholar. I even had the opportunity to meet figures like Yogi Naraharinath at our home and was inspired by his ability to converse in Sanskrit for hours.

We had a repository of nearly five thousand books, a rare treasure in a rural setting. My father’s library was rich in ancient texts like the ‘Vedas’, ‘Upanishads’, ‘Mahabharata’, ‘Ramayan’, and other philosophical works, while my elder brother’s collection leaned more towards Nepali and Hindi literature, as well as social sciences and economics. Through them, I gained access to both ancient and modern knowledge.

Later, I had the privilege of working with Bhanubhakta Pokharel, the 1990 Madan Puraskar recipient, who always encouraged me to read extensively, even beyond a PhD. His words stayed with me. I also engaged in enriching intellectual exchanges with Indian professor Brij Kishore Kuthiala, helping me refine how I shape and present my ideas.

How does your passion for literature relate to your work in communication theory?

Books are the first love of my life. There were times I would read for twenty hours straight, exploring all kinds of genres without limitation. That habit nurtured my imagination, which now plays a vital role in my academic writing. Academic papers and journal articles can often feel less interesting so, I try to bring in the richness of language and expression I absorbed from literature. The literary sensibility I developed helps me craft academic work that’s not just informative but also engaging.

You have explored ancient texts like the ‘Natyashastra’ for communication theory. What did you find most relevant in these texts for modern-day media studies?

While studying Mass Communication and Journalism, I got to learn theories from Western perspectives. At the same time, I began exploring ancient Eastern texts like the ‘Natyashastra’, which significantly shaped my work. In fact, my research based on the ‘Natyashastra’, especially the Sadharanikaran model of communication, has been widely received and is now part of university curricula around the world. I believe its popularity stems from the depth of ‘Natyashastra’ itself. It is a time-tested text, often called the sixth Veda, that continues to influence culture, society, performance, and aesthetics even millennia later.

From any disciplinary lens, the ‘Natyashastra’ offers something valuable. For me, it opened up a rich repository of ideas relevant to communication theory and practice. It discusses kinesics, nonverbal communication through gesture and posture, music as a tool for emotional expression, the use of poetry to evoke shared feelings, and detailed guidance on drama and theatre. It teaches us how to communicate holistically and how to ensure effective, meaningful exchange. All in all, it provides insights that remain relevant in today’s media landscape.

Many call your work an example of indigenous theorisation. What challenges did you face when positioning Eastern frameworks in a predominantly Western communication academia?

The real challenge in positioning Eastern frameworks wasn’t international but domestic. Interestingly, when my work reached global audiences, it was welcomed. But here in Nepal, the response was often paradoxical and even discouraging. During my MA orientation in Mass Communication and Journalism, I asked why our syllabus included only Western theories and suggested incorporating indigenous knowledge. The entire hall laughed. But the head of department responded thoughtfully, saying that communication had long been West-centric, and perhaps people like me could now help bring eastern perspectives and theories to the table.

With that encouragement, I wrote my dissertation. Gradually, I discovered others who shared similar ideas. I met scholars who had begun exploring this terrain. Still, my peers and much of the media fraternity remained sceptical. It wasn’t until I started publishing in English in Nepal and abroad that recognition grew. My breakthrough came in 2010 when my article on the Sadharanikaran model and Sancharika Siddhanta was published in China Media Research, a journal simultaneously published from the US and China. That drew interest from scholars in India, Indonesia, China, and the US.

By 2016, the model was included in the International Encyclopedia of Communication Theory, the only communication theory from a non-Western region featured there. Ironically, it was only after gaining global acceptance that it began receiving appreciation at home.

Do you believe the future of media studies lies in more localised or indigenous theories?

Rather than going to the dichotomy of global versus local, I prefer taking a rooted local approach while staying informed about international practices. Understanding global perspectives is important, but staying connected to our own intellectual and cultural sources is equally vital. I often tell my students to balance the three C’s: classic, contemporary, and context. When we integrate these, we cultivate a more holistic and meaningful approach to media studies.

Nirmala Mani Adhikary’s five book recommendations

Shridurgasaptashati

Author: N/A

Publisher: Geeta Press (new edition)

Year: 2021

This book celebrates the divine feminine. Having always been close to my mother, I’ve felt connected to this energy since childhood.

Laxmi Nibandha Sangraha

Author: Laxmi Prasad Devkota

Publisher: Thuprai (new edition)

Year: 2021

I love this text because it uses poetic language in prose. It beautifully balances imagination and reason, which makes it worth reading.

Natyashastra

Author: Bharatha

Publisher: Munshiram (new edition)

Year: 2014

Bharatha’s book is like a vast ocean—anyone who enters is sure to be touched by its waves of wisdom.

The Razor’s Edge

Author: William Somerset Maugham

Publisher: Doubleday, Doran

Year: 1944

Maugham tells the touching story of Larry Darrell, an American pilot traumatised by his experiences in World War I.

Shlokavartika

Author: Kumarila Bhatta

Publisher: Chandan Rai Chowdhary

Year: 1985 (new edition)

Though challenging to read, this book is worth the effort. It’s the kind of Sanskrit philosophical text that deserves to be read multiple times.

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu