Books

Reading Mo Yan in Nepali: A journey into China’s soul

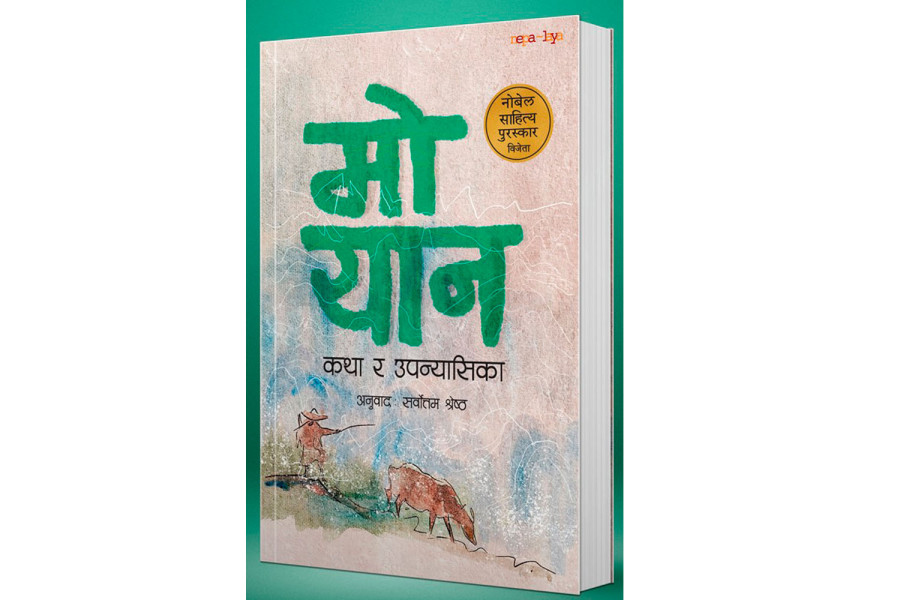

The translated collection, split into two parts, includes seventeen short stories and two compelling novellas.

Sushma Shakya

When ‘Mo Yan: Katha ra Upanyasika’, published by Nepalaya and translated by Sarbottam Shrestha, first came into my hands, I was expecting a glimpse into another literary world—not a dive into a surreal, brutal, yet strangely beautiful world that was both foreign and strangely familiar. The stories are strongly infused with a Chinese flavour and covered with hallucinatory realism, lore, satire, and everyday problems of ordinary people. They were not just stories but worlds to live in, demanding one’s total concentration and leaving one with long shadows much after the last page.

Mo Yan, the 2012 winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, is defined by a method that does more than tell—grasps, pierces, and exposes. His sharp realism can sometimes be uncomfortable, and his talent for blending the physical, emotional, and symbolic into a seamless narrative is exceptional. This translated collection, split into two parts, includes seventeen short stories and two compelling novellas: ‘Seto Kukur ra Ping’ (‘White Dog and the Swing’) and ‘Phool Bokney Yuwati’ (‘The Woman with the Flowers’). The translation conveys the rhythms and textures of Mo Yan’s writing, so Nepali readers experience the same jolts, blanks, and troughs as his original readers.

Among the short stories, ‘Divya Aushadhi’ (‘Divine Medicine’) is notable for its stark accuracy. The scene where a man’s heart and liver are removed is described so vividly that it causes a physical sensation—an ache in the reader’s chest. Mo Yan’s realism is neither softened nor symbolic; it’s visceral, unwavering, and precise. He demonstrates that plain, unembellished violence can be more disturbing than the most elaborate horror.

‘Surung’ (‘The Tunnel’) broke illusions regarding China’s One-Child Policy. For foreigners abroad, the policies seemed to be concretely and unconditionally put into practice, with an authority that left little room for disobedience. But from this story, it is seen that there was indeed resistance—silent, tentative, but human. In describing the lives of common people, Mo Yan proves that despite repressive state supervision, personal freedom of choice and delicate acts of rebellion can prevail.

The emotional load of ‘Anna’ is of a different kind. Based on real life, it shows a mother’s desperation and determination to do anything to feed her children. The quiet heroism here is not in flamboyant gestures but in grim struggle against hunger and despair. It evokes deep respect and leaves the viewer with an aftertaste of guilt—a reminder that the next time food is wasted, somewhere someone is making unconscionable sacrifices just to put a meal on the table.

Not every story in the collection is strictly based on fact. Some, like ‘Raatma Machha Marna Jada’ and ‘Hawaii Udan’, edge towards fantasy, an otherness that hovers between dream and reality. These moments of enchantment and strangeness interrupt the bleakness of the harder stories, but they are always linked to the emotional realities that weave the collection.

The book mainly connects through shared human experiences. Even though it is set in rural China, themes like poverty, family duty, superstition, ghosts, and survival are familiar in Nepal too. Across Asia, people share similar struggles and values, so while the details differ, the core experiences feel the same.

The second-half novellas display another aspect of Mo Yan’s art. In ‘White Dog and the Swing’, heroine Nuan, a one-eyed female, lives in a world of silence—her husband and three sons are speechless and her own voice a voice of silence in suffering. Her unexpected and shocking request to the narrator to be the father of a child who can speak is both heartbreaking and morally complex. It forces a confrontation with questions of survival, dignity, and the limits of compassion. The writer uses stillness and rural metaphors to turn silence into a potent storytelling device.

‘Phool Bokney Yuwati’ (‘The Woman with the Flowers’) feels like walking through a dream. The figure of the central woman, draped in flowers and a decaying shawl, is less a character than a living symbol. She becomes an emblem of lost time, frustrated desire, lost loveliness, and perhaps guilt. The prose here is rich, sensual, and hypnotic, inviting the reader not to solve the mystery but to stay suspended. It is a story to be felt, not spoken, a narrative that obsesses the subconscious like a half-remembered nightmare.

The anthology has its frustrations. Some of the stories are slow-moving, and for those not used to symbolic or highly metaphorical writing, some of the pieces will seem to slip away. There are instances in which the story appears to close up the truth, leaving it unrevealed. This will infuriate those expecting clear cut storytelling, but it is also part of Mo Yan’s style—to leave the reader just a little bit disturbed, to force them to continue the narrative in their own mind.

The novellas, however, catch with more force. They create tension that invites the reader deeper, page after page, with that implicit but insistent query: what happens next? This protracted pull is one of Mo Yan’s hallmarks—the ability to turn uncertainty into an end in itself to keep reading.

Reading this series is like stepping into a world where the real and the imaginary blend, where beauty and ugliness go hand in hand. Mo Yan peels off the mask of society, history, and mankind, showing how fiction can be dreamlike yet very real. Though grounded in modern China, his stories broadly illustrate universal human feelings that resonate beyond national boundaries.

This is not only a window into China’s rural heart but also a mirror. In it, Nepali readers will perhaps see echoes of their own villages, histories, and unvoiced struggles. For all those who seek literature that breaks conventions, provokes contemplation, and inspires empathy, Mo Yan has a haunting and indelible journey.

______

‘Mo Yan: Katha ra Upanyasika’

Author: Mo Yan

Translator: Sarbottam Shrestha

Publisher: Nepalaya

Year: 2025

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu