Books

I keep digging the endless depths of Sanskrit and philosophy

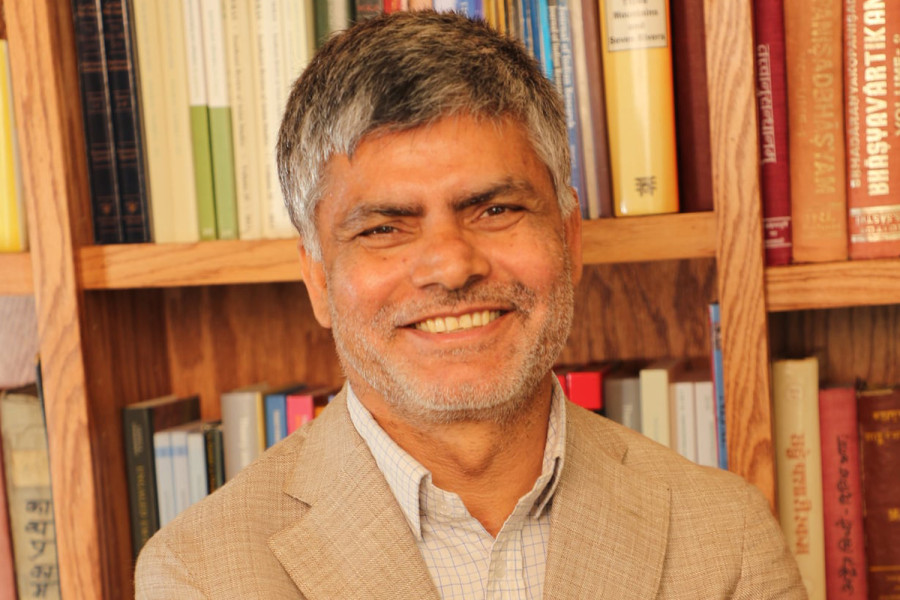

Professor Sthaneshwar Timalsina reflects on the challenges of institutionalising Tantric studies and differences in how Eastern and Western students engage with philosophy.

Sanskriti Pokharel

Sthaneshwar Timalsina is a professor and the ‘Nirmal and Augustina Mattoo Endowed Chair’ in Classical Indic Humanities at Stony Brook University. Born in Dhading, Nepal, he is a product of the traditional gurukula system, having studied under several gurus before earning his PhD in Classical Indian Philosophy from Martin Luther University, Halle, Germany.

He teaches across Indian civilisation, focusing on philosophy, Tantra, and Sanskrit traditions. Over the past three decades, he has taught in Nepal, India, Europe, and the United States, including positions at San Diego State University, the University of Hawaii, and Washington University in St Louis.

Timalsina is the author of several influential works, including ‘Tantric Visual Culture: A Cognitive Approach’ (2015), ‘Language of Images: Visualization and Meaning in Tantras’ (2015), and ‘Consciousness in Indian Philosophy’ (2008).

He aims to revive and make accessible neglected humanities disciplines across India, Nepal, and the West. His work connects classical Sanskrit studies with modern philosophy, art, and cognitive science.

In this conversation with the Post’s Sanskriti Pokharel, Timalsina discusses the challenges of institutionalising Tantric studies and the differences between Eastern and Western students’ engagement with philosophy.

What drew you towards philosophy and Sanskrit?

I was drawn to philosophy and Sanskrit because of the circumstances I was born into. My father was a pandit, and from an early age, he began teaching me the Vedas and Sanskrit grammar. By the time I was sixteen, I met my mentors who started training me full-time, six days a week.

Indeed, I likely had some personal interest as well, but I can’t claim credit for it. My father and my gurus guided me toward this path, and I feel grateful for that. Had it been left entirely to me, I may have made the wrong decision.

Back then, we didn’t have as many options as students do today. Dedication came naturally, simply by observing how my teachers lived, the depth of their knowledge, and their commitment to learning.

What inspired me most to study Sanskrit was its fundamental structure. Its mechanics, almost like a form of chemistry. Each word could be broken down into parts and then reassembled with prefixes, suffixes, and verbal roots that transformed one form into another, almost like witnessing a chemical reaction unfold. From this process, meaning would emerge in the most surprising and beautiful ways.

Even more fascinating was how, through analysis, one word would lead to another and reveal layers of meaning that were not visible before. Every word became a subject for reflection, something to meditate upon for hours. That richness, that endless unfolding of meaning, was what truly captivated me and kept me rooted in Sanskrit and philosophy.

What kind of books do you read? Are you always inclined towards philosophy and Sanskrit literature?

I don’t usually read just one book at a time. At the moment, I am reading several works on Chinese philosophy. Before that, I was exploring the writings of the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, particularly his works ‘The Logic of Sense’, ‘What is Philosophy?’, and ‘Difference and Repetition’. I am deeply interested in many of the philosophical debates of the 21st century in the West.

For me, reading philosophy always connects back to Sanskrit. I often think of Sanskrit not as something like a mango that you can squeeze, take the juice from, and be done with. It is more like ice. Once you start cracking it, the whole structure begins to melt and unfold. Sanskrit keeps opening up new possibilities.

Every time I encounter new philosophical ideas, I find resonances with classical Sanskrit thinkers, such as Abhinavagupta. That is what makes my reading so engaging, the dialogue between contemporary philosophy and the timeless depth of Sanskrit thought. Whatever energy and attention I have, I dedicate it either to reading philosophy or to my own writing.

You founded the Department of Tantric Studies at Nepal Sanskrit University in the early 90s. What inspired that move?

Looking back after so many decades, I would say founding the Department of Tantric Studies was both exciting and challenging. It gave me immense satisfaction.

The inspiration came from my Guruji, Prem Chetan Bramhochari, who was a sadhaka (individual on a spiritual path). I had the privilege of receiving training from him when I was sixteen. He often told me that tantric sadhana had traditionally been practiced either within families or through the guru—disciple relationship. Most tantric practices were passed secretly, often from father to son. But he also pointed out that this model could not survive in the modern generation.

In fact, it was already in decline. At one time, there were more than fifty vidyapeethas across India and Nepal where students could receive training directly from yogis and yoginis. That is no longer the case. Yet, looking around, you see that so much of our culture is rooted in tantra. The statues, temple structures, and even texts like Mayamata are based on tantric knowledge. Everything from temple renovation, daily puja, and the process of pran pratistha in idols comes from tantra. If you travel across Nepal, the abundance of Shiva and Vishnu temples you see are also products of tantric traditions.

My Guruji told me that this knowledge should not remain confined to secrecy or dismissed as mere occult practice. It needed to be institutionalised, made into a discipline that could be studied in a secular and scholarly way within a university setting. Founding the department was, in a way, my guru dakshina to the teachers I was fortunate to have, both in Nepal and in Varanasi.

When you moved to the West, how did you approach presenting Tantra in an academic setting where there were misconceptions about it?

When I first came to the West, the challenge was very different from what I had faced in Nepal. It was not about orthodoxy but about misconception. For most people, Tantra simply meant sex. That was the popular assumption, and I had to work hard to shift the conversation toward its deeper philosophical and artistic dimensions.

Since my goal was to reach the educated masses rather than establish myself as a public guru, I realised that the most important task was to theorise. The Western academic world is deeply rooted in theory, and without it, the discussion would not carry weight. My first serious attempt at theorising was in my work ‘Time and Space in Tantric Art’. From there, I continued to think more deeply and expand my arguments.

You’ve taught in both Eastern and Western institutions. How do students’ engagements with Indian philosophy differ between the two contexts?

This is, of course, a broad generalisation, since every classroom has both bright and not-so-bright students. But there are noticeable differences. In Nepal, many students come from a background of faith. Their engagement with Indian philosophy is often shaped by belief, which means they may not ask many questions. For example, they would rarely question someone like Shankaracharya, because tradition and reverence guide their approach.

In the West, it is quite different. Students usually study these subjects out of curiosity, not faith. They don’t necessarily believe in what I teach, but they are intrigued and amused by it. Because philosophy demands questioning, they challenge ideas more freely. They can question anything, since they are not bound by the authority of the tradition.

At the same time, this openness comes with its own challenges. Western students can sometimes be overly skeptical. Their questioning does not always lead to deep engagement, and often their interest remains shallow. They may switch from one subject to another each semester without committing to any particular field.

So, in both contexts, there are advantages and limitations. As teachers, it becomes our responsibility to meet students where they are and guide them into a deeper understanding of the subject.

If someone unfamiliar with Indian philosophy wanted to start exploring, what books would you recommend?

For anyone beginning to explore Indian philosophy, I would recommend starting with the ‘Bhagavad Gita’.

Sthaneshwar Timalsina’s five book recommendations

Yoga Vasishtha

Author: N/A

Publisher: Bharatiya Publishing House (new edition)

Year: 1976

I keep coming back to this book because it contains captivating stories and is simple to read.

Spanda Kairikas

Author: Jaideva Singh

Publisher: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (new edition)

Year: 2020

Singh presents a synthesis of Shaiva philosophy, portraying metaphysics as a dynamic rather than static reality.

Ka

Author: Roberto Calasso

Publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Year: 1999

This book includes teachings from classical Indian philosophy, and uses beautiful language for modern-day readers.

Vakyapadiya

Author: Bhartṛhari

Publisher: Sampurnanand Sanskrit University (new edition)

Year: 2015

Many see ‘Vakyapadiya’ as a Sanskrit philosophy book, but it is about how reality is connected to language.

Being and Time

Author: Martin Heidegger

Publisher: Harper Perennial Modern Thought (new edition)

Year: 2008

The book by Heidegger had a notable impact on subsequent philosophy, literary theory and many other fields.

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu