Books

Ramite: Who is the fairgoer?

By using multiple narrators, the author, who is also the leader of the musical band, Night, anchors us to his fictional world with the sumptuous use of deictic expressions.

Bal Bahadur Thapa

I go across Dhuljeng, mother, don't sit back to cry

Does it matter even if I don't return? I have gone to touch the star in the west

Steel your heart, sisters, save your tears

A time will come to cry and laugh together (89, Ramite)

The first thing that struck me while reading Jason Kunwar's debut novel 'Ramite' was its language. It sounds raw, rustic and fresh. Since Jason does not anchor his creative universe to any actual place from Nepal, it certainly takes a little patience on the part of the readers to get the hang of the novel. On top of that, you will not find any Godlike narrator to guide you. For a while, you will wonder: Where am I? Where are Khile and his friends wandering? Soon, however, you will come across Uga, where Khile and his friends are from. You know that there is no place called Uga or Laku, but you won't find it queasy, mythical or artificial like 'Kalpanapur' or 'Dukhapur'.

Through his multiple narrators, Kunwar, who is also the leader of the musical band, Night, anchors us to his fictional world with the sumptuous use of deictic expressions. He peoples his fictional world with the villagers, who, by no standards, sound fictional at all. If you are from a village or if you have observed any Nepali village, you will quickly identify Khile, Khural Kaka, Nili, Tuhuri, Dumre, Ilakha and Beli with the villagers you have known. Furthermore, most places have mythical histories (e.g. the myth of Yogini and the king Trichapilla concerning Trichathat) sustained by oral tradition the way every Nepali village has. This is the nature of the history of the places on the margins. No official history!

In such a startlingly realistic universe under the garb of fictionality, the characters live their life with all sorts of problems the people do in the villages and small towns across Nepal: famine, migration, nationalism, natural calamity, violence against women, psychology of dependence and its devastating consequences, generational conflicts between and among villages and whatnot. Though the novel seems to grapple with more social issues than it can chew, they will never hinder the narrative flow. Those issues are embodied by characters and events, not presented through long and tiresome commentaries of the omniscient narrator or any holier than thou sort of character.

The important characters take their turns to tell their stories. This sort of narrative technique lets the female characters have their voices without any mediation. Tuhuri, Beli, and Pabu's mother, who are victims of patriarchy, take their turns to tell us their stories. Like many women from our society, these female characters undergo the sufferings at the hands of their male counterparts under one or another excuse. As two young girls die of the sexual violence inflicted on them by Dumre and his friends, Tuhuri asks, "What does a man need? How much does he need?" Sounds familiar, right?

Nevertheless, the women have not been portrayed as hapless characters or the romanticised subalterns who can't be wrong. Instead, they, with their share of weaknesses, make decisions about their life and they struggle hard against violence and oppression in their own ways. They are the backbone of the villages, which have suffered from the loss of adult males because of migration. Khile describes his beloved Nili's mother in these words: "Her mother's body had carried the whole suffering of the house. . . . She would single-handedly dig and plough the terraced paddy field of Tirman Kaka." Such representation of women sounds ethical on the part of the novelist. To foreground the plights of women, Jason does not deprive them of their subjectivity.

The ethical representation is not limited to women. It is equally applicable to the antagonistic characters like Dumre. Nothing is black and white in 'Ramite' indeed. It does not let us have a complacent pleasure of witnessing the victory of good over evil. Instead, it encourages us to see things from multiple perspectives. It appeals to us to live grappling with questions for solving our problem rather than savouring the smugness of illusory closure or resolution. Characters are as complex as we are. Even the seemingly villainous character like Dumre can be as captivating and endearing as his nemesis Tuhuri. One can't help but feel like embracing Dumre out of empathy as we learn about his quest for his mother, who, failing to put up with her husband's violence, hangs herself to death on a tree called Umrek. At the death of his mother, Umrek itself becomes his mother.

In addition, 'Ramite' forces us to think of the international migration of our sisters and brothers from all parts of Nepal. Poverty, famine, natural calamities, inter-village conflicts and superstitious practices force the characters to cross the dangerous cliff of Dhuljeng to go beyond Birasar. We can also see the seasonal migration of the characters to other villages in search of work. Even a noble practice of 'Dash parma' seems to be a veiled portrayal of migration. Indeed, Khural Kaka, in his conversation with Khile, hints at famine as a reason behind 'Dash parma'. Highlighting the reasons behind the migration of males from Laku, Tuhuri says, "Neither can they protect the honour of their women nor can they feed their family properly. To a husband, to a father, no defeat is bigger than this. No wound is deeper than this." They decide to cross Birasar to bring happiness back to Laku. The place beyond Birasar has been portrayed as 'the bright world' the way America, Australia, Europe and Gulf countries appear to most Nepalis desperate to escape their villages and towns in search of a better life now.

No writing is perfect, and 'Ramite' is no exception either. Sometimes, you might find it too dark and dismal. You might wonder what the awkward-sounding words like 'lodyaunu' and 'mantha' stand for. The author could have resorted to ordinary Nepali words. Likewise, the inclusion of the story of Tutu and Bantu, though an interesting one, seems unneeded. It does not have a direct connection to the narrative thread Jason weaves through the voices of multiple characters. Sometimes you might feel that the novel has no conventional resolution. Several narrative threads are left hanging. For example, you may wonder if Khile and his friends get back to their village Uga from the arduous journey of 'Dash parma'. But this is also the beauty of this novel. It is not about individuals. It's about our life. Life goes on regardless of death, failure or success of an individual.

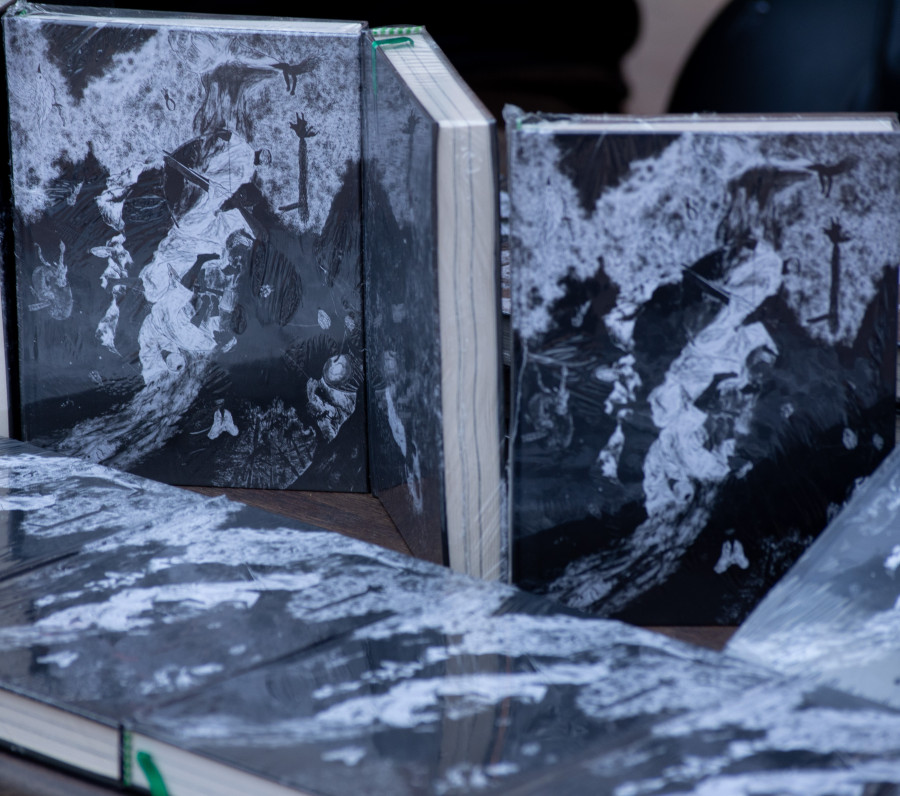

Due to very few glitches, the novel's language flows like a river. The cover design looks bold, evocative and innovative. 'Ramite' is free of sloppiness, which marks even the remarkable works of Nepali literature in terms of language and design.

'Ramite' makes an impossible attempt to portray the rural Nepali society in its totality. The non-linear and fragmented narrative, punctuated and carried forward by maps, meaningful songs, paintings, and mysterious codes, poses an intriguing puzzle. One does not need to be a rocket scientist to figure out that the society portrayed is fair. But as you finish reading it, you will be left wondering: Who is the fairgoer? You? The author? Khile and his friends? Who? It is not a novel that you read and put away for good. It's a novel, which tickles and challenges you to get back to it again and again. Even after reading twice or thrice, you wonder if you have been able to solve Jason's narrative jigsaw puzzle.

——————————————

Ramite

Author: Jason Kunwar

Publisher: Redpanda Books

Pages: 282

Price: Rs 850

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu