Arts

Reinforcing self-identity through graffiti art

Alejandro Poli Jr, aka Man One, is a first-generation Mexican-American who is following his passion and making a career out of graffiti art.

Bishesh Dhaubhadel & Tsering Ngodup Lama

What happens when a 16-year-old boy gets passed a marker to tag a bus out of the blue? If you ask Alejandro Poli Jr, aka Man One, a renowned graffiti artist, the answer is the boy discovers a passion to pursue and go on to make a career out of graffiti art, all the while making art as accessible to everyone as possible.

Born in 1971 in Los Angeles, USA, Poli Jr is a first-generation Mexican-American who grew up listening to hip-hop music. Before he got into tagging and dedicated himself to street art, he had his eyes set on becoming either a b-boy artist or a DJ. The former didn’t pan out when he found he wasn’t physically equipped to make the b-boy moves that were trending at the time, and he had to give up his DJ dreams because his parents couldn’t afford the equipment required.

As a huge hip-hop music fan, Poli Jr started tagging as Mantronix, a popular hip-hop band in the 80s, at 16. But he soon started tagging as Man One simply because Mantronix was too long, and he would often get spotted by people before he could finish his act.

“Tagging isn’t legal, and the thrill of doing it anyway and getting away with it was why I enjoyed it so much,” says the artist.

While tagging buses and public properties might’ve kept Poli Jr busy in his teens, self-admittedly, he eventually got tired of it and wanted to move on to doing bigger and more elaborate pieces of street art. One of the reasons that made him want to move away from tagging was his parent's concern.

“Back then, tagging and graffiti were instantly connected to gang culture in the eyes of viewers who weren’t familiar with the art forms. My parents thought the same, and they were worried I would become a gang member,” he says. “To convince them that I wasn’t in it for the gangs and that I was serious about becoming a legitimate artist, I decided to get a degree in fine arts.”

This proved to be a turning point in his artistic journey and how he saw and understood art. College was where Poli Jr learned art history, design, colour theory, and more.

“When I first began learning about colour theory, it completely changed how I look at colours and use them. Not everyone needs to go to college to become an artist, but it is essential to learn the rules. You have to learn the rules to break them,” he adds.

After getting his degree in fine arts, Poli Jr started making consistent progress and was beginning to get commissioned art projects. But perhaps the most significant event in his career might’ve been the 1992 Los Angeles Riots, a series of riots and civil disturbances that erupted in the city against police brutality. After the riots, the local government started to acknowledge graffiti as a powerful artistic medium to talk about socio-cultural issues.

“For years, LA’s graffiti artists had used street art to address and make people aware of social issues like racism and police brutality,” says Poli Jr. “We were very well aware of the medium as a force for social change, but it was only after the riots broke out that the city started seeing graffiti in the same light.”

After the riots, the city’s government even started commissioning graffiti artists to make murals and also allotted “open walls” to let the children practise graffiti without having to worry about being harassed by the cops, which helped popularise street art. In the early days of his career as a professional artist, Man One admits to having faced his share of harassment from law enforcement officials.

“This one time, I was working on a piece for the cable TV network VH1, and the police pulled up and held our group—including an eight-year-old—and me—at gunpoint. The director had to rush out and convince the police that I was an artist and wasn’t doing anything illegal. After the heat, one of the officers looked at the art and complimented, saying it was “a beautiful piece of art”. And I replied, “Yeah, you almost had us killed for that art.”

Quite clearly, there still exists a negative view around graffiti art, especially since it has long been a “protest art”. Artists often face harassment from the authorities and backlash from members of the society.

“Some artists think that if it’s not illegal, it’s not graffiti,” said Man One. But he thinks graffiti goes beyond that. According to the artist, graffiti doesn’t need to be illegal to have a meaning, and his objective is to make art accessible to everyone, without the repercussions for indulging in it.

During the initial days of Man One doing commissioned works, many from the artist community even labelled him a “sellout”. But the scenario has changed dramatically. “Today, artists are collaborating with all kinds of brands, and they take pride in that,” says Man One.

In the over two decades that Man One has operated as a professional artist, he has done commission work for brands like MTV, Vh1, Coca-Cola, and multinational companies. He has also worked with the US government on several art-related projects. It is this collaboration with his country’s government that brought him to Nepal in the final week of November for the Street Art Project 2022, an initiative that focused on the theme of social inclusion and equity. The project was organised by Artudio, a Kathmandu-based contemporary art collective/platform, in collaboration with the US Embassy in Nepal.

The key objectives of the Street Art Project 2022 were to showcase the creative potential of graffiti art to inspire social change and establish critical public dialogue on key issues of inclusion and equity and create a platform for underrepresented artists to reach new policymakers.

As part of the project, Man One worked with several Nepali artists and even travelled to Janakpur and conducted a graffiti lettering session at a local school and painted a graffiti piece for the establishment.

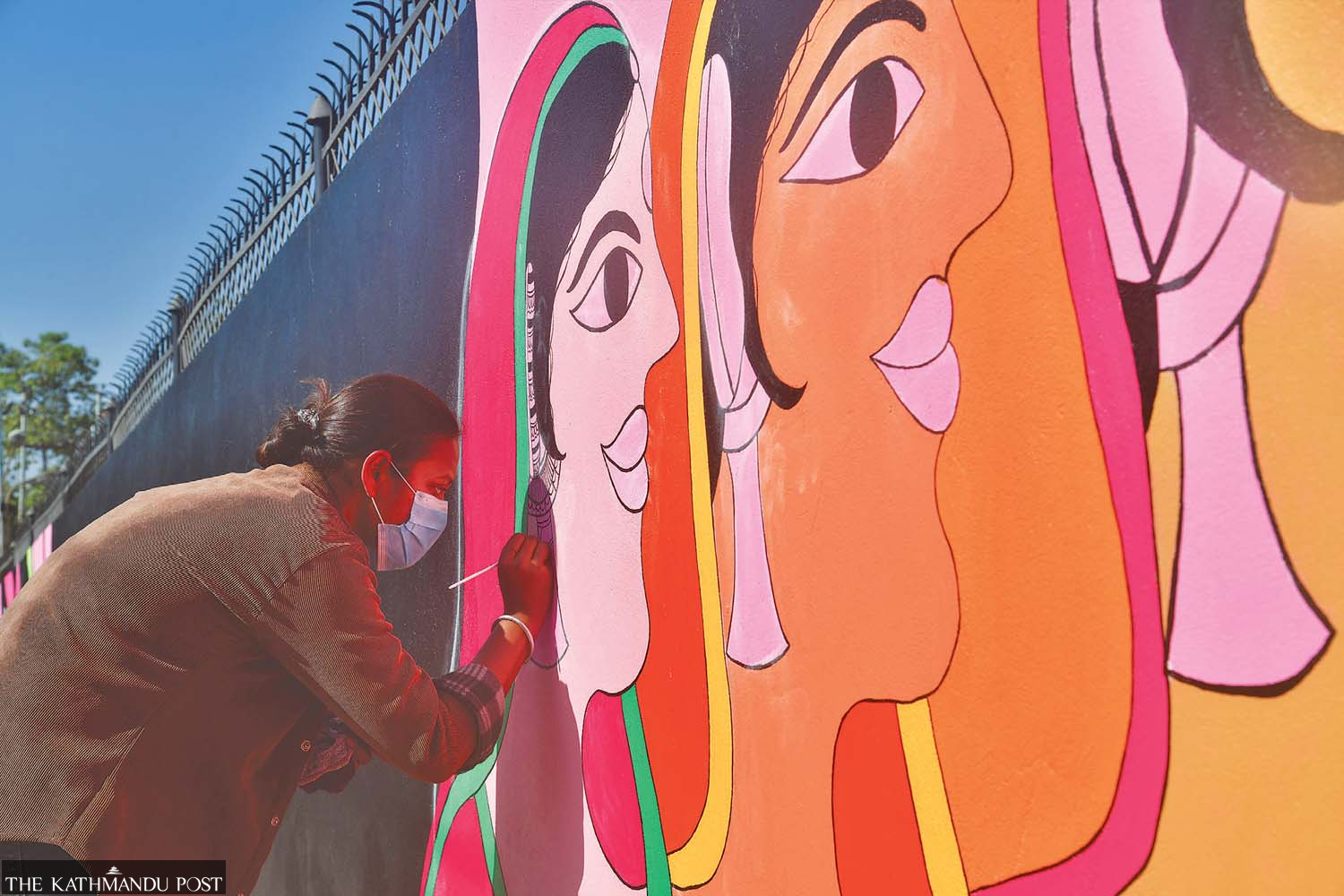

Poli’s general ethos around inclusivity in art and democratising it, ties into Artudio’s Street Art Project 2022 theme of social inclusion and equity. The project concluded with Man One collaborating with Nepali artists to make “a 120 feet long” mural dubbed, ‘Ekata’.

The project, says Man One, allowed him to work with countless artists he’s never heard of before and “learn about Mithila and Thangka art” that he might’ve never heard of in LA. And the Nepali participants found an opportunity to not just collaborate and learn with an internationally renowned artist but also to make connections with other Nepali artists with whom they are likely to partner in the future to further the graffiti art scene in Nepal.

As a first-generation Mexican-American kid growing up in a racially diverse community in LA, when Man One tagged his first bus, he had never imagined that it would lead him to embark on a long artistic journey.

“For me, art, be it in the form of hip-hop music or street art, has always served as a medium to express myself,” says Poli Jr. “The beauty of art is that its language is universal. It doesn’t matter whether you are from the US, Nepal, or Panama, we all speak the language of art, and we all interpret it in our way. That’s the power of art.”

20.78°C Kathmandu

20.78°C Kathmandu