Arts

Examining human-nature ties

The group exhibit ‘Interdependence’ gathers Nepali women artists to reflect on our fragile relationship with nature’s five elements—earth, water, fire, air, and space.

Aarya Chand

Stepping into ‘Interdependence’, curator Michelle Lama presents a meditative exhibition on humanity’s relationship with the five elements—fire, water, earth, air, and space. This gathering of Nepali women artists bridges rural and urban worldviews, their works forming a collective inquiry into how contemporary existence has disrupted the delicate equilibrium of our natural world.

From the clay of traditional pots to the natural dyes of handwoven textiles, the materials whisper of connection. Each piece is doubly anchored: in the enduring wisdom of nature and a quiet awareness of its fragility. The exhibition compels viewers to pause—not just to observe, but to reckon with the deeper work of conservation. What does it mean to preserve the environment, heritage, or community when all are inextricably linked? How do we honour the threads that bind us to the elements and to one another?

Through diverse creative lenses, ‘Interdependence’ challenges us to reconsider what we’ve lost—and what we might yet restore—in our fundamental kinship with the forces that sustain life.

Sushma Shakya’s ‘Pancha‑Tattva’ installation takes its name from a Sanskrit phrase meaning ‘five elements’. She highlights how the harmonious interplay of earth, water, fire, air and space underpins Nepal’s ecosystems and, by extension, our very existence. The polished wooden panels, etched with subtle elemental motifs, show growth in the crevices as if the materials themselves breathe the ecosystem’s pulse.

At moments, the work explicitly confronts urban life’s disconnect: stylised masks hang beside smog‑shrouded cityscapes, plastic bottles float into a stylised riverbed; an air‑conditioner vapour looped into a cloud. It urges us to consider more than quick fixes—efforts to mask environmental ills rather than address their root causes. Alongside scenes of woodland and hillside fertility, the work strikes a balance between critique and suggestion, speaking of hopeful transformation even as it acknowledges loss.

In the same room we can see Sushila Singh’s ‘Mana Pathi’ which is a homage to traditional Nepali measurement vessels—the mana and pathi, a sculptural poetry. The pots, cast in clay and glazed in deep black, are punctuated by delicate gold highlights around their rims. The effect is tactile yet intimate, as though one might lift these objects, feel their weight and recall ritual uses: measuring grain for offerings, calling the community to gather.

The black-on-black palette conveys mystery and time’s passage; the gold signifies the preciousness of heritage. By adding two more vessels—golpa, for ritual grain, and taukhola, for communal feasting—Singh reminds us that these elements carry shared values as much as they hold grain or water. The pots stand as quiet testaments to lives once built around seasons and sustenance, asking how we preserve such traditions when convenience prevails over connection.

Then comes Tenzin Sangmo’s installation of ‘Weaving Elements’ of fifteen textiles, including a traditional Dolpo keti apron, which reads as a quiet memoir of Himalayan life. Each piece mirrors an element: earthen browns, river blues, flame reds, pasture greens, sky whites. Patterns echo agrarian cycles and mountain seasons; the cloth holds stories of planting, harvesting and winter’s retreat.

The keti, with its geometric embroidery, becomes a ceremonial focal point. It resonates as cloth, both protective and symbolic, full of ancestral meaning. These are not overly polished weavings, but work that reflects human touch and imperfection—gentle reminders that nature itself is never uniform.

Sangmo speaks of hope that her daughter may learn this craft—which feels like a hopeful whisper amid global change. Yet there is a steady melancholy in the fading whites and browns: an elegy for melting ice, shifting climate, and intangible traditions edging towards memory.

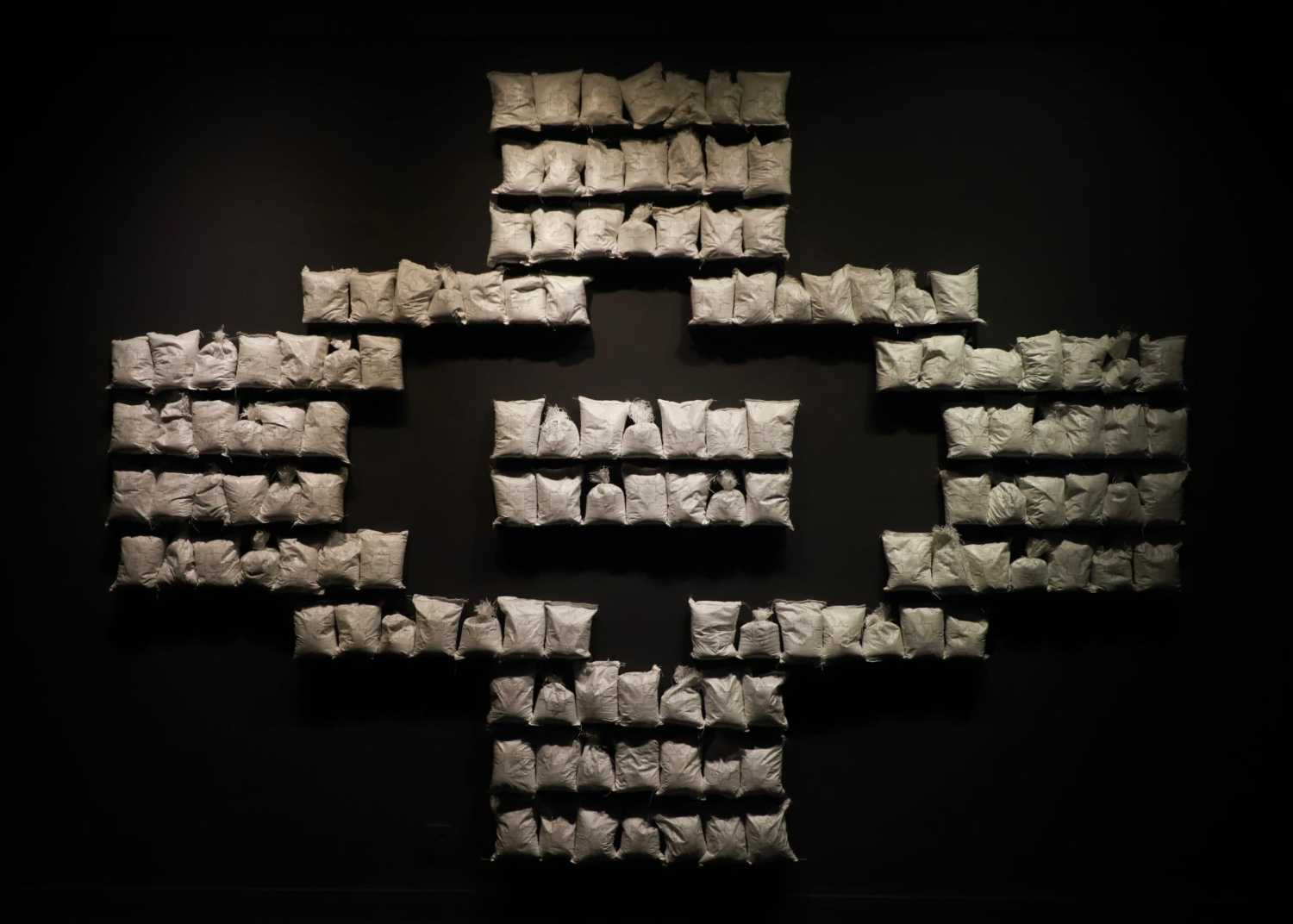

I found Bidhata KC’s ‘Silent Dependencies’ unique. At first sight, it appears to be an ordinary cement sack hung slightly askew. But its material—concrete—speaks of earth and water, lime kilns heated by fire, air trapped in the mix, the space it defines when shaped. The work becomes a meditation on human construction and elemental origins: how all industrial creation begins with forces of nature, yet becomes divorced from them once enclosed within walls.

KC intends the sack to represent both a material object and a concept. It speaks of the unseen system—the soil, humidity, heat and void—that binds it to existence. In stillness, the form seems to breathe: a subtle invitation to recall our roots, the elemental cycles we weave into daily life, often without noticing. An important piece because it questions what we commonly overlook.

This framing of interdependence becomes visual and symbolic in the collaborative work of Rashmi Karn and Vaishali Chhetri, who revive Mithila art’s traditional patterns in their series focused on the five elements. In Mithila tradition, space and form exist together—there is no background or foreground. Everything matters equally, and this is where their exploration of interdependence becomes philosophical and material. Each element is rendered through motifs and colour, not as singular entities but in relationship with one another. Fire feeds on air, water nourishes the earth, and space holds them all. The artists do not try to modernise Mithila style; instead, they allow its original grammar of union and ritual to highlight the fragility of ecological and social balance today.

Before the final works on the top floor, the exhibit also gives context to a recent trip by artists to Ghandruk. Even though their mediums vary, the trip’s influence binds them thematically: remembering stone, water, plants, textiles and humans in elemental dialogue.

Shreenidhi Khadka’s mixed-media series ‘Here, There, Everywhere’ is grounded in black—perhaps a nod to stone paths or memory itself. Her colours build slowly: blue, pink, brown, then white. These aren’t landscape paintings, but recollections layered over time. They appear structured at first, then increasingly unbound, like a gradual letting go of form. It’s not difficult to imagine these as visual diary entries—daily impressions, caught in transition.

The personal tone continues in Shreya Bajracharya’s ‘Looms of Affection’, where a garland offered by a schoolboy in Ghandruk becomes the starting point. Her response is subtle but textured: a woven impression of the moment that feels both specific and anonymous. In a show that dwells heavily on environmental shifts and cultural loss, her work reminds us that interdependence includes emotion and care—between people as much as between elements.

Anu Maharjan in ‘Arranged for You’, adds another layer by highlighting the artificiality that often masks natural beauty. When she finds herself unable to pick a flower from the ground, she instead creates a print of it—flattened, framed, preserved. Her work raises a question that feels urgent in urban life: when access to nature is curated, what do we actually experience? The flower becomes not an object of admiration but of absence.

Samip Limbu’s paintings draw attention to stone—not as passive infrastructure, but as something that holds stories. His paintings show window sills, stone ledges, drying laundry. These aren’t grand scenes, but everyday arrangements. Stone, here, is not background—it’s a medium, shaped by and shaping the human body. Like KC’s cement sack, it asks us to reconsider what we think of as inert.

But this isn’t where the exhibit ends. Beyond these works, several others continue the conversation—each offering distinct ways of seeing the elements not in isolation, but in quiet, constant relation. Together, they form a steady rhythm of inquiry—less like a conclusion, more like an ongoing cycle.

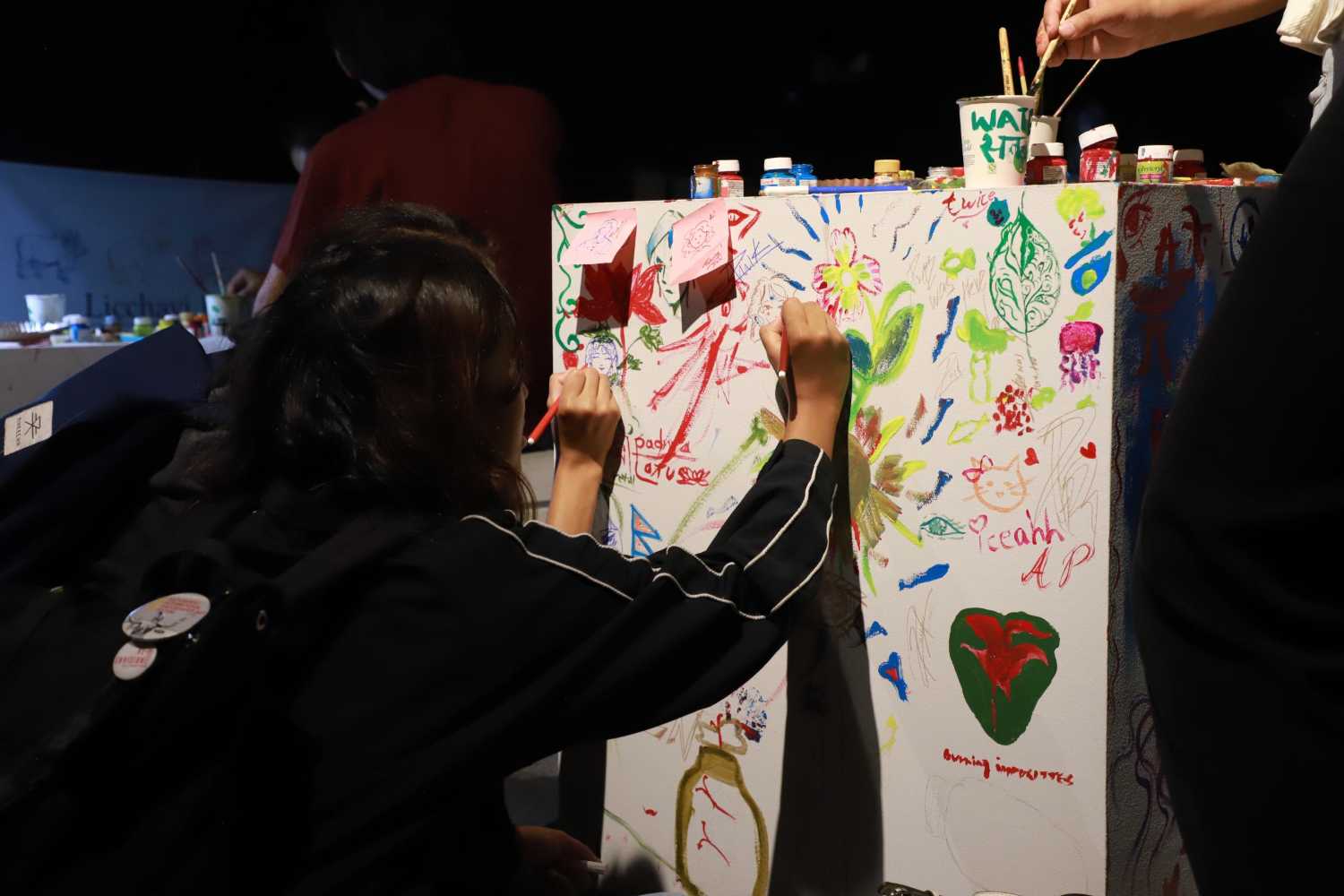

In the midst of all this, one part of the exhibition stood out to me not just for its content but for the experience it offered. An interactive space had been set up where visitors could sit, rest, and create. Paper, colours, stones, and leaves were available. I sat with my friends, and together, we painted, exchanging small pieces as mementoes. It felt less like an activity and more like a gentle invitation to participate in the flow of the exhibition—to respond, in our ways, to what we had seen. That moment of stillness, shared creativity, and reflection remains with me. It made the exhibition feel not only viewed, but lived.

Throughout ‘Interdependence,’ the artworks speak in relation—each pot, line, sack, thread, and colour exists in connection rather than isolation. More than a theme or visual device, the five elements become a way of thinking. This exhibit is about the conditions that hold them all, and the people trying to hold on to those conditions carefully, without romanticism. That care is what lingers as one leaves the space.

________

Interdependence

Where: Nepal Art Council, Baber Mahal, Kathmandu

When: Till 12 July

Time: 11:00 am to 5:00 pm

Entry: Free

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=200&height=120)