National

Student visa interviews resume but changes in US visa policy add challenges

Pending interview requests and new requirements set to make visa applications harder.

Ellie Davis

This spring, Bishwo Jeet Bista was accepted into Harvard University’s class of 2029, but unpredictable changes in US policy on student visas have left him unsure whether he will be able to attend school in the fall.

For students accepted to US universities who are hoping to study in the country in the fall, changes in US policy on student visas have made the visa process harder.

Student visa interview appointments opened again for scheduling Tuesday at 8 am, but after more than a month-long pause in interview scheduling, a backlog in interview demand and new requirements directing visa applicants to make their social media accounts public will make the visa application more cumbersome.

The US Embassy would not comment on whether they expect further disruptions in visa interview scheduling.

The Trump administration put a hold on the scheduling of visa appointments on May 27, and although the hold officially ended on June 18, students in Nepal anxiously waited for nearly an extra two weeks with no word from the US Embassy in Kathmandu on when scheduling of visa appointments would resume. The US Embassy did not comment on the reason for the delay.

Bista scheduled his visa interview ahead of the scheduling ban, but US visa policy changes have gotten in his way. Two days before his June 6 interview, Donald Trump issued an executive order barring Harvard from admitting international students. After his interview, his visa was categorised under the US State Department policy 221(g), a status of “administrative processing,” during which the embassy gathers more information or documentation before it accepts or rejects the visa application.

On June 6—the same day as Bista’s interview—a US District Court Judge blocked Trump’s ban on Harvard international students with a temporary restraining order. Despite the judge’s orders, when Bista went back to the US Embassy about two weeks later, he learned that his visa had been denied because when he completed his interview, the court was yet to block Trump’s executive order.

A US Embassy official told Bista that the timing of his interview was bad luck, Bista said.

Bisa’s case is unique—his visa rejection is a direct result of action from Trump’s executive order, and, as far as he knows, he is the only undergraduate student from Nepal to be accepted to Harvard’s class of 2029. Had he known of the trouble he would face in getting a US visa, he would have also applied to higher education elsewhere, he said.

“If I was applying this year instead of last, I would not make the United States the only place I applied to,” he said.

If he can’t gain a visa before the start of his bachelor’s programme in September, Bista will have to defer his Harvard acceptance. “I’m in limbo right now,” he said. “I don’t know what to expect, so it’s difficult to imagine where I’ll be next month.”

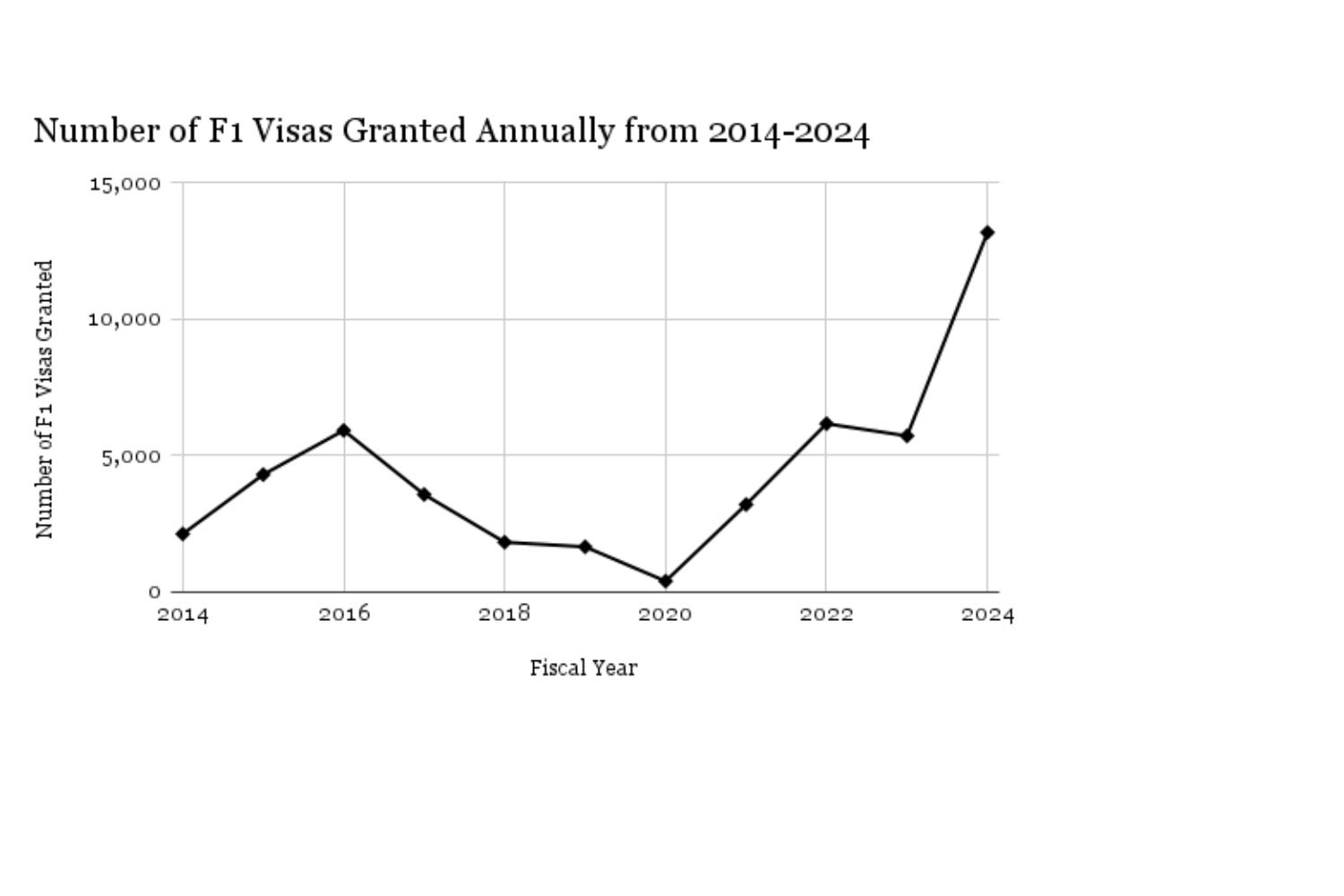

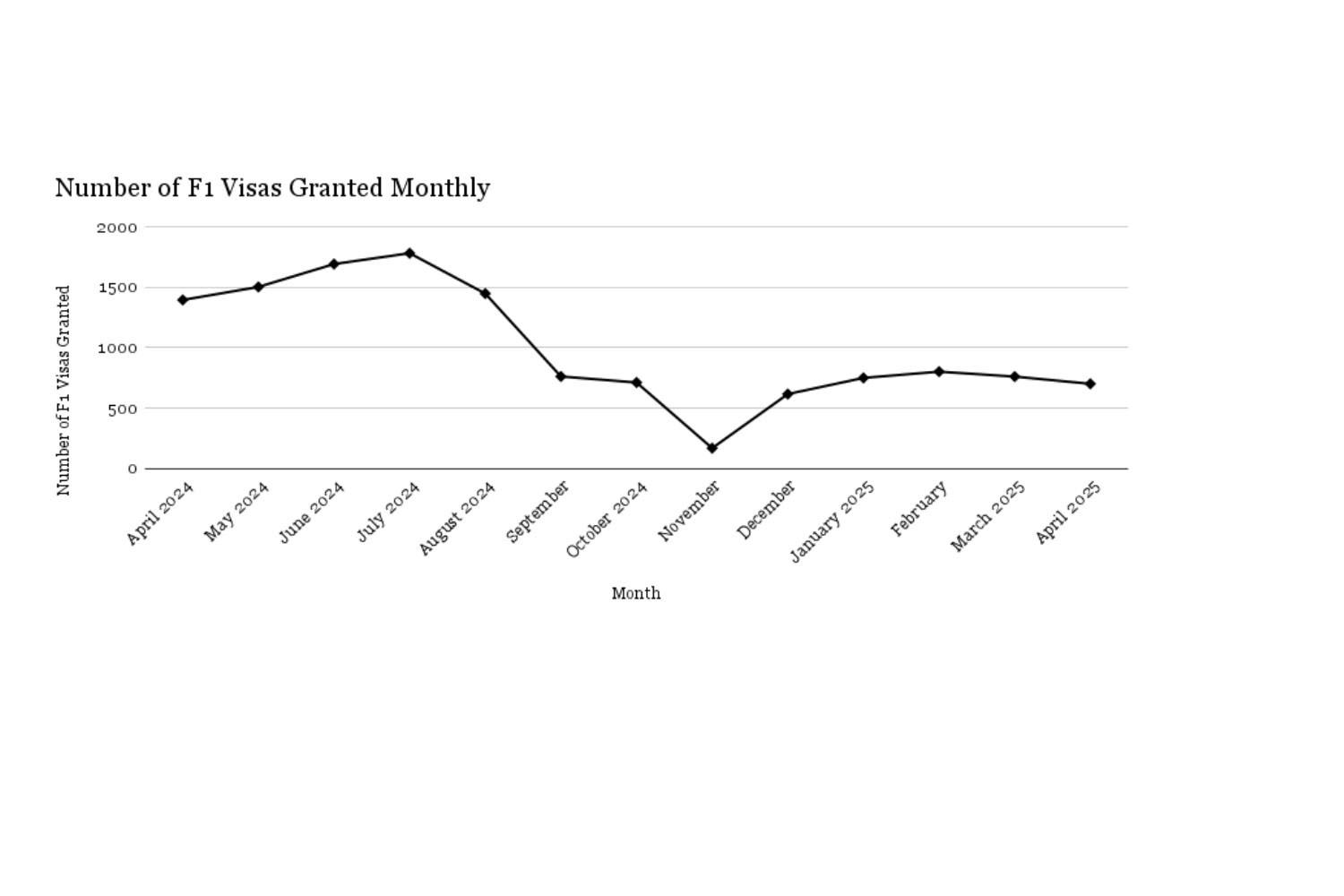

Bista’s visa troubles coincide with a recent downward trend in the number of F1 student visas granted by the US Embassy in Kathmandu. In April, the embassy granted 701 F1 student visas, according to the most recent data from the US State Department. As of April this year, the embassy had granted 4,509 visas—compared to 5,990 visas in the same period last fiscal year.

The fiscal year 2024 saw a new record for F1 visas in Nepal, with the embassy granting 13,187 F1 visas, more than double the previous year.

After a month without any visa interview appointments being scheduled, other students accepted to US universities worry they won’t be able to secure an interview slot due to the backlog in demand. Bikram, who the Post is identifying with a pseudonym, has been accepted to study at the University of San Diego in California, but for the past few weeks, he has been waiting for the US Embassy to resume visa interview scheduling.

“I would have probably already given my interview if [the interviews] weren’t paused,” he said. “It’s beyond our control, but it’s frustrating, to say the least.”

Bikram is not paying an education consultancy to help him navigate the visa process, and he worries that on his own he won’t be able to get an appointment. He’s waiting for paperwork from his university to apply, but based on his older sister’s experience trying to book a visa interview, he worries that he won’t be able to get an interview time.

He plans on being at his computer for hours each day to try and book a slot. “It’s gonna be really hard as the consultancies book all the days,” he said.

Other students have encountered challenges with the new instructions from the US Embassy to make their social media accounts public to “facilitate vetting necessary to establish their identity and admissibility to the United States,” the Embassy said in a statement made Thursday.

“Omitting social media information on your application could lead to visa denial and ineligibility for future US Visas.”

Sunamika Karki, an aspiring master’s student, hopes to begin her programme in data science at the University of Missouri in September. She had her already scheduled student visa interview on June 24, but her visa was placed under administrative processing, and the embassy told her to make sure all her social media accounts were public.

According to BM Khadka, CEO of Edwise Foundation, two other students at the consultancy have their visas placed under administrative processing while they follow the embassy’s instructions to make their social media public. Khadka hopes Karki will get an answer within a week, and in the meantime, he instructed her to make sure that all of her social media accounts, including her LinkedIn, are public.

For some students, the added hurdles associated with the US visa process make the allure of studying in the US not worth it. “Some of them have started to reconsider the United States, which hasn’t been the case in the past,” Khadka said.

Director of Leaf Education Consultancy Prakash Lamichhane said that since US President Trump’s second term in office began, interest in studying in the United States among the students he sees has plummeted. He used to work with between 50 and 100 students every year hoping to study in the US. Now, that number is in the single digits, he said.

“With the new administration, they are not comfortable with how immigrants are being seen,” Lamichhane said. “Maybe things will change, but right now it is not looking good.”

Despite the added challenges, some students have remained steadfast in their desire to study in the United States.

Nineteen-year-old Bijesha Hyoju was accepted to start studying fashion design at Seattle Pacific University in Washington in September. Even though her visa was rejected after her interview on June 18, Hyoju doesn’t plan on giving up.

“I got so sad at first, but I won’t stop,” she said. “I will go to the US because it is my dream.”

Moving forward, students and education consultancies are unsure how US policy will impact students’ ability to study in the US. Country Manager Sailesh Kuman Jha at AECC Study Abroad Consultants, one of Nepal’s largest education consultancies, hopes that eventually political circumstances in the US will evolve to minimise barriers for international students.

“We all know the Trump regime has changed the policy,” he said. “But the US will come with a new policy sooner or later.”

16.92°C Kathmandu

16.92°C Kathmandu