Entertainment

Finding fame, and the right words, on the right social medium

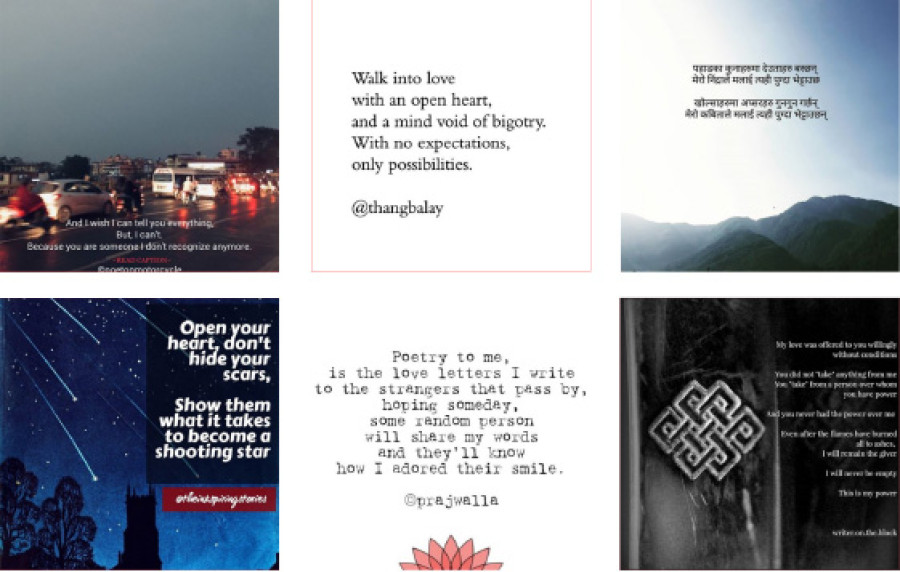

After a global takeover by Instagram poets, Nepali poets are now making their way to the social media platform.

Sweksha Karna

Over a plain white background, subtly outlined with a spade, a few lines in the centre read, “We feed the dead artist while the living one dies.” The photo is posted from Ashim Sharma’s Instagram account @wolves.of.words, where he posts similarly-styled posted with poetry. Although his prose is typically short, akin to quotes, this particular post has garnered more than 430 likes, and has comments like “Brilliant” and “I don’t know how I found you on IG but I’m glad I did.”

The trend of posting poetry on Instagram gained traction after Cambodian-Australian poet Lang Leav, who mostly posted poetry on Instagram, sold more than 150,000 copies of her book Love & Misadventure in 2013. Additionally, with Canadian poet Rupi Kaur’s Milk & Honey listed as a #1 New York Times bestseller in 2017 and Atticus’ The Dark Between Stars nominated for Goodread Choice Awards for Best Poetry in 2018, both Instagram poets having more than a million followers on Instagram, ‘Instapoetry’ has cemented its place in the social media platform worldwide. In Nepal too, Instagram poetry has started to attract a large audience, with more than a dozen poetry accounts catering to poetry lovers.

Sharma, who has almost 8,000 followers on his Instagram account, has also published a poetry collection, Poetry in Denim. While his 2018 work didn’t gain as much attention in mainstream media as his international counterparts, he has not been deterred.

“I started posting in 2015, right after the earthquake. It just started out as an outlet to express the emotional turmoil I was going through,” Sharma says. “But now, I realise that I can be a voice. People started commenting that they related to my writing, and it has become a platform that pushes me to sharpen my skills.”

Instagram, which was primarily designed to be a platform for sharing photos and videos, has become a portal for creative people to show-off their aesthetic sensibility. Like sharing photos of food, travel and everyday photography, Instagram poetry started to thrive in the same course, birthing a whole new genre, now popularly known as Instapoetry—and it’s especially popular among young people.

“I have neither the time, nor a very good sense of literature, to read long, metaphorical poetry,” says Priyanshu Rai, a 21-year-old MBBS student. “Instagram poetry is short, relatable and appealing, which is why I prefer it.”

For decades, poetry was thought of as a slow and dusty artform. But many consider the advent of Instagram poetry to have a larger democratic effect on the entire genre. The young audience, especially millennials, seem to have connected with this form, which shirks the usage of convoluted or complicated language. However, the trend may have transcended its seemingly young audience base, with Nielsen BookScan, which gathers data for the book publishing sector, pointing out poetry book sales jumped 66 percent between 2012 and 2017. Many have taken this as proof that Instagram has helped poetry come back into favour.

But not all share the similar sentiment. Some disagree with the legitimacy of Instagram poetry in its entirety. Teacher Menka Adhikari says Instagram hosts nothing but random assortments of words, assembled without thought. “If you ask me, Instagram poetry is pretentious. It’s for kids who think that going through some trouble in life automatically makes them a poet.”

Texas-based poet Thom Young even made a parody account for instapoets and Andrew Lloyd made a fake instapoetry account to mock poets on Instagram and prove the work is redundant. Both wanted to prove that Instagram poetry accounts were only aimed at gaining followers and rarely put any thought into poetry.

But it isn’t just the followers or the audiences that question the relevance of Instagram poetry. Astha Bhandari (@infinity.poetry) who is one of the first Nepalis to post poetry on Instagram agrees that when she first started posting, it wasn’t necessarily poems. “If I’m being very honest, I posted what I felt like posting. They were just quotes and ideas,” she says.

Some are still not deterred, with many Nepali Instapoets like @themayushrestha with over 2,200 followers and @thangbalay, with 201,000, who are still very active and have considerable audience engagement.

“My question for people who question Instagram poetry would be, what is real poetry?” says Ashim Sharma. “Poetry is way up there among the undefinables.”

According to him, Instagram has contributed to reviving a love of poetry among people. “Poetry has become reachable and accessible due to these platforms. They serve as a mediator, even an amplifier in a way, they are reviving love for poetry.”

Sharma’s belief has been supported by the global wave that has come to accept Instagram poetry. The UK’s National Poetry Library even held its first-ever exhibition devoted to the social media poetry last year.

Instapoetry found popularity because of the shortened length of the verses that work well on a phone, and because they’re easy to share. This not only gives poets a platform to share their work but also to build their brands on their own volition. Rather than relying on publishers, the poets can control their aesthetic, content and audience, where ever they are.

But this can be a double-edged sword, some poets say. With the fast-paced nature of social media, sometimes creators’ hunger to build their following can not only compromise the quality of their content but build unhealthy amounts of pressure on them to stay relevant.

“I posted every thought that crossed my mind. At one point, it got really exhausting because I couldn’t stop myself from chasing numbers,” says Bhandari, who goes by @infinity.poetry. “Then I decided to take a two week break. But when I came back, I had lost a considerable amount of followers. I guess I could never recover from that.”

Her current follower count doesn’t even reach 50, but it used to be more than 1,200 in 2016.

Sharma, who strongly believes Instagram had been a great launching pad for poets, also agrees there are some drawbacks.

“Artists need to change their style and voice to suit their audiences, so much so that they lose their identity,” he says. “It can also affect their sense of self-worth, if they are too focused on numbers, negative comments, and the algorithm. Then there’s the frustration of not being able to grow the page.”

With this pressure of constantly feeding the audience, many instances of plagiarism have come to light. In July 2017, Rupi Kaur was accused of plagiarism by another Instagram and tumbler poet, Nayyirah Waheed. Waheed went on to write about how she was upset as the issue wasn’t addressed, despite reaching out to Kaur personally. Kaur remained silent and did not talk about the incident at all.

“It’s not that difficult to plagiarise on Instagram. I’ve seen people copying poems from bigger accounts and sharing them shamelessly,” says Bhandari. “Smaller accounts do this to gain more attention and more followers, and big accounts do it when they’re running out of things to post.”

Like in Rupi Kaur’s case, sometimes these issues have no consequences at all. But both Sharma and Bhandari say the best way to keep an audience engaged and build a brand is to focus on the content, rather than advertising, collaborations or aesthetics.

“It’s ultimately our poems they are following us for,” says Bhandari, who admits she has no intention of returning to Instagram poetry.

The growing global phenomenon has promoted discourse surrounding the validity of Instagram poetry, compared to the artform’s ink-and-paper predecessors. Although Nepal hasn’t seen the same amount of debate yet, Sharma says it is even more useful as hardly any publishers are encouraging young poets or publishing their work.

“Hopefully we will have more poets on Instagram in the future and we can grow as a community,” says Sharma. “But with the fast-paced nature of the world and technology, anything is almost impossible to predict.”

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu