Entertainment

For the love of art

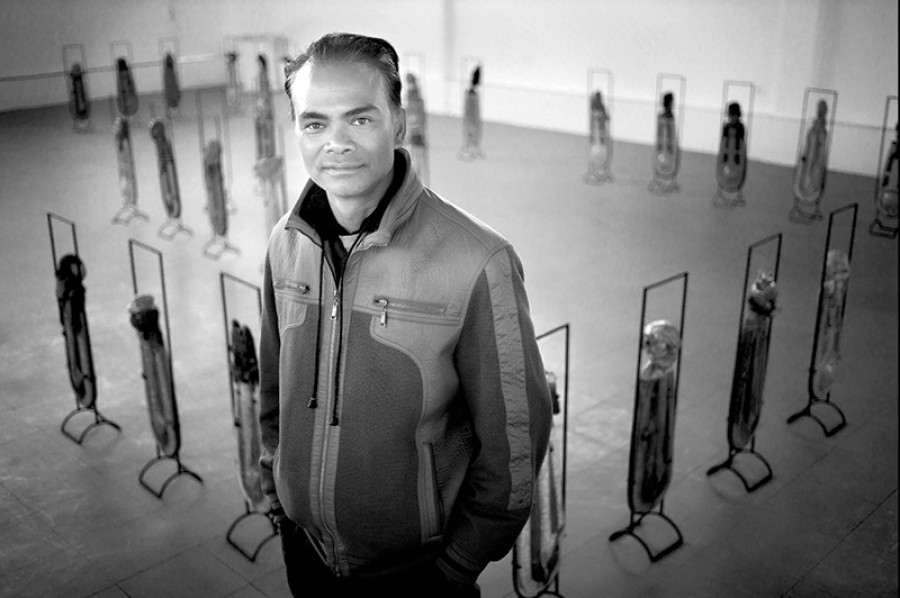

The stories of the greatest artists are often those of adversity and speaking to Gopal Shrestha, the “Kalapremi”, or Art Lover, an epithet the artist uses himself to signify his life’s passion, is a rare experience for an art historian.

Sophia L Pandé

The stories of the greatest artists are often those of adversity and speaking to Gopal Shrestha, the “Kalapremi”, or Art Lover, an epithet the artist uses himself to signify his life’s passion, is a rare experience for an art historian. The artist’s eloquence, gravitas, and extreme erudition do not bar him from speaking in layman’s terms, explaining his journey and life’s work in a manner straight out of a scholarly journal. In these days of internal conflict for contemporary artists, particularly in Nepal, it is not easy to extract the obstacles, inspirations, motivations, and explanations of artistic choices from the practitioners, but Gopal is an exception.

Born in 1965, with an artistic bent that began at an early age, Gopal Shrestha is largely self-taught. His childhood was spent going to school in the mornings, working in restaurants afterwards for pocket money, and playing in the mud, creating art. As he grew older and delved deeper into the arts, his focus on sculpture shifted to a keenness in the form of ceramics, a happy accident that came about when Gopal was asked to train Nepali potters in Bhaktapur and Thimi in an attempt to add market value to their existing lovely, but quotidian pots.

As he trained, he had to show, and so Gopal learnt all the technical aspects of what it means to make pottery. And when combined with his artistic senses of enrichment, he was able to help people elevate an earthen pot into a work of art, in the process he was himself transformed from artist to a ceramist—one of the highest order.

In his twenties, Gopal would repair homes as an electrician, plumber, and painter, working through the 1980s in Kathmandu landmarks such as the Ambassador Hotel and the now demolished Hotel Kathmandu. For about 13 years, Gopal made his living as a handyman, all the while gaining the technical skills he would use later on in life to bring the works in his mind’s eye to life.

Trained formally only at Kathmandu’s Lalit Kala Campus, Gopal soon went on his own way, learning more from books, environments, and colleagues than from his teachers at a time when these art schools did not really have bonafide teachers. With his experience of training potters, he had already realised that Nepal could not compete with manufacturing, next to our gigantic neighbours, India and China; instead, our country could provide its very own, very unique handicraft for export.

Over the next decade, Gopal then trained and ran a workshop of over 26 workers who produced handmade, intricate pottery. But running around making receipts, paying bills, and managing people and things was the worst part of that job, he says, explaining that he could only do his artwork in passionate stretches at the time. When Gopal gave up the workshop, he left it to his students who still run it successfully in Thimi.

Being self-taught means that Gopal Shrestha, the art lover, is a renaissance man, of a kind, when it comes to the arts. He is able to speak about the origins of chess, the semantics of Newar, Sanskrit, Urdu, Hindi, and Nepali words. This ability, to range from subject to subject, deeply and not as a dilettante, is what makes his art so very rich.

In the landscape of Gopal’s mind, a few exhibitions stand out for him. His first exhibition in 1998 was shown by the architect Sarosh Pradhan in the Kathmandu Art Gallery. Titled ‘Love from Peace’ the show consisted of freestanding ceramic sculptures made from black ware ceramic (known as “haku thala kuma”, the black (haku) pot (thala) made by a kuma, or potter). Here, Gopal’s involvement with the feminine form, and feminism was apparent, with each of the sculptures exploring different kind of love between various aspects of the feminine, from mother to son or between men and women.

Since his first show, Gopal has had 13 solo exhibitions in various places, but it is the show titled ‘The Darker Days of My Country’ in 2005, that is most important to him. Already a master with his hands by then, Gopal was struggling internally, depressed by the state of the country. Medicated (his world had become black and white and he could no longer see things in colour), he would break the ceramic plates he was making, joining them again in remorse and in hope. That exhibition in the NAFA Art Gallery was an experience and a life lesson also: He could not sell any pieces, a few were bought but never picked up—a stark reminder of how difficult life as an artist continues to be in Nepal.

Today, Gopal’s shows have become almost mythical in their importance. His works of the Raku glazing technique that he mastered after a workshop in India, and then taught to himself via books he would get from abroad from helpful friends, are on a scale that nobody else in the world really works in today.

For ‘Pakdai, Bikdai Manchhe’ 44 of his epic figures (out of a planned 108) were fired in public in Bhrikuti Mandap by Gopal and his students who wanted to show the average person the technology behind ceramics, and in particular the distinctive webbed Raku technique that requires firing these 24 inch high figures at a temperature of 1100 degrees Celsius. With the mould of the body made out of the stock shape of a bicycle cover (which covers the inner workings of a bike) so do the bodies of these ceramic figures, each representing a tradition, person, or mythology, hide the real person behind the ceramic façade. ‘Pakdai Bikdai Manchhe’, or ‘People being Bought and Sold’, is a metaphor of how we, as people, are made, and sell ourselves or are sold over the course of our lives, even while we may remain unaware of these transactions.

With Gopal’s epic show ‘Masculism’, the master ceramist made 48 bulls to turn the idea of a deified masculinity on its head. While the work can be interpreted in many ways, some controversially, these realisations of the sacred bull, tattooed against his will (only women are tattooed in various tribal Nepali cultures) in white and blue sold out within a few weeks.

Today, at the Siddhartha Art Gallery, there is an opportunity to see ‘Nari Satranj’, Gopal’s new show that is the feminine analogue (though conceived ten years before the bull series) to ‘Masculism’, showing a fictitious world where women play the game of politics, and of life. The entire chess board (or satranj) is made up of 32 female players even as 18 other women wait in line for their chance to play. This is your opportunity to see a superlative body of work, one that took Gopal over three years to make. If you are a kalapremi, you must not miss it.

15.12°C Kathmandu

15.12°C Kathmandu