Entertainment

The Man Who Knew So Much

When I first approached Sukra Sagar Shrestha for an interview regarding the Char Narayan Temple earlier this year, he initially declined the request, thinking I was a journalist. He did not want any such attention.

Sophia L Pandé

When I first approached Sukra Sagar Shrestha for an interview regarding the Char Narayan Temple earlier this year, he initially declined the request, thinking I was a journalist. He did not want any such attention. The Resident Archeologist at the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT), Shrestha, I’d been recommended, would be the best person to speak at length about the vast, complex iconography that defines the Newar arts of the Kathmandu Valley.

Only after he realised that I wasn’t working for any media, did he open up and become radiantly willing to share his vast experience. But scheduling a recorded audio interview with him took time—he was not well, diabetic, and always watchful of his weight. He baked and carried his own bread, walked everywhere, and looked a bit frail, despite the brightness in his eyes.

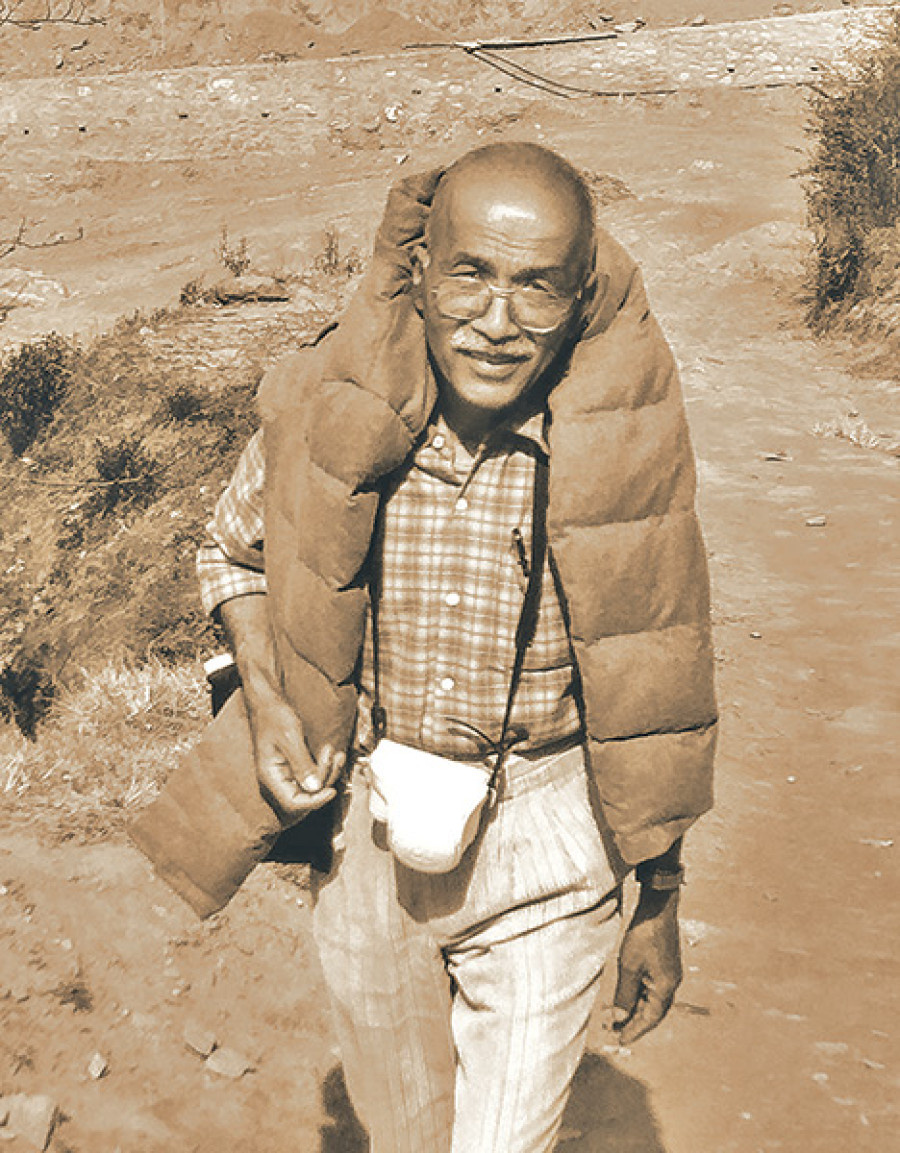

Finally, a few weeks later we managed to sit down to speak, and the conversation initially began with my inquiries into how the cult of worshipping Narayan came about in the Kathmandu Valley. He was a wealth of information regarding this and so many other subjects that our interview ran very long, touching on so many fascinating subjects. At the time, I reluctantly came to a stop thinking I would have time in the future to pick his protean brain. I never took a photo of him either, though I meant to. A few weeks later, Shrestha passed away in the hospital at the age of 64.

The outpouring of grief was expected; the man was incredibly well respected but also beloved by those who worked with him. Raju Roka at the KVPT office remembers fondly his gentle, generous approach while imparting knowledge, Rohit Ranjitkar, KVPT Nepal Program Director tells of how Sukra Sagar Sir would frankly correct any thing he thought inaccurate in a straightforward manner that is so unusual to the Nepali modus operandi.

In his long interview with me, when he was conversing on various subjects, he mentioned how his career was a series of him walking out on institutions which had somehow frustrated him. In his youth, he was asked to make the first Himalayan Profile of the mountains at the Department of Tourism. At the time, tourists would come to Nepal but there was no documentation on the names, distances, and other aspects of the Himalayas to give to them. Shrestha travelled for nine years compiling the information. When it was done, he handed it over and left—he was at odds with the then Minister of Tourism; it was his habit to not hold his tongue. He then spoke of his subsequent eighteen years at the Department of Archaeology. He worked there till he was a hundred and four days away from becoming the Director General, the highest office in the Department. He resigned because again, things did not suit his frank personality, which saw right and wrong very clearly.

Sirish Bhatt, KVPT architect, who worked with him on a National Geographic documentary that was filming the cave culture of Mustang, reminisces about his incredible memory, his wide interests, his attentiveness while imparting knowledge, his humbleness despite his vast learning, and his apolitical attitude that guided his moral compass and caused him to leave both government departments despite his swift rise and clearly promising prospects.

Towards the end of his life, which no one saw coming, Shrestha was working on two very promising projects, a book, soon to be published, on erotic carvings (people are always thinking the wrong things on the subject, he said) that he worked on with Wolfgang Korn, and another work that was to document all of the idols across the Valley; a sort of counterpart to Lain Singh Bangdel’s seminal book from 1989 The Stolen Idols of Nepal, but inclusive of every made image—an invaluable contribution for future scholars to trace what might be lost.

Today, all those whose path crossed Sukra Sagar Shrestha’s shake their heads at the loss that is yet to hit us, even as we realise, day to day, that his gentleness, humour, and sharp observant eyes are no longer accessible to us. A true scholar with a hunger for learning and an aptitude for teaching, he never stopped researching the Valley that he loved so much, and was so proud of as a Newar of Kirtipur. In one of the last words in my interview with him he said, “Who will come to Kathmandu Valley if all we see is a concrete jungle? We have to rebuild, it is the priceless heritage of the Newars that bring people here”. I hope that we can abide by his wishes.

16.92°C Kathmandu

16.92°C Kathmandu