Culture & Lifestyle

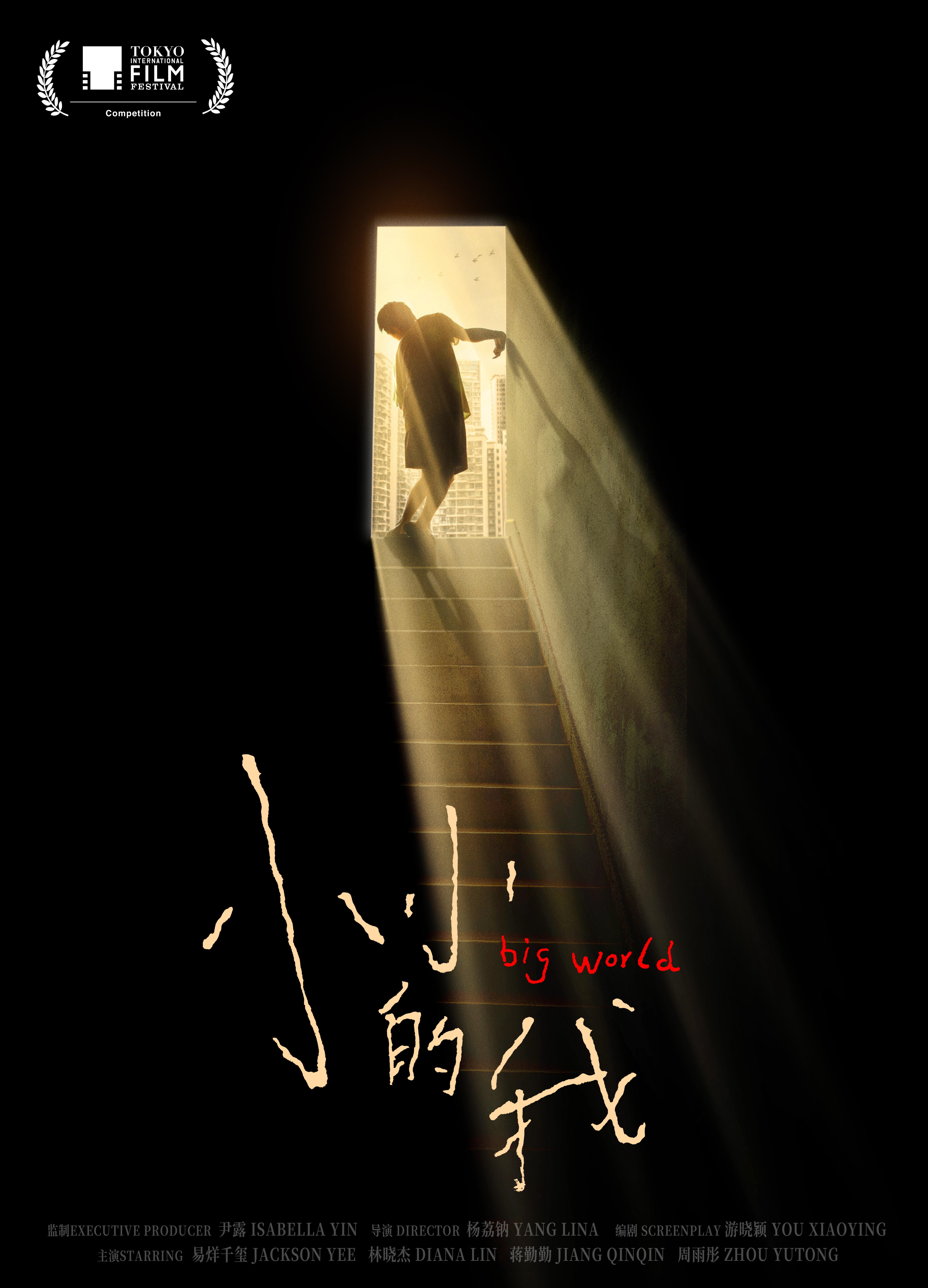

‘Big World’ is not perfect, but important

The touching movie explores dignity, love and the complexity of human bonds.

Aarya Chand

In ‘Big World’, director Yang Lina delivers a quietly devastating coming-of-age tale of Liu Chunhe, a teenager with cerebral palsy who dares to live on his terms. What might have easily been a sentimental story is instead presented with grounded realism, subtlety, and a commendable refusal to pity or glorify its subject. As a psychology and literature student and, more importantly, a young adult witnessing peers around me still relying on parental support, Chunhe’s story left a lasting impression on how we define independence, love, and acceptance in a world that often chooses convenience over compassion.

“Having a job is dignity,” this quote, said with unwavering sincerity by Chunhe, is more than a line. It is the emotional axis of the film. From the outset, Chunhe refuses to be reduced to a patient or a burden. Despite the difficulty of walking and speaking and being raised by a controlling mother who insists she knows what is best, Chunhe insists on applying for jobs, standing in queues, and earning his own money. He dreams of getting accepted into a regular university and becoming a teacher, not a special institution, not something curated for him, but the same path any other able-bodied student might take.

When his mother, Chen Lu, tries to use her savings to place him in a private university, Chunhe’s quiet but firm resistance brings one of the most tension-filled but realistic parent-child conflicts to the fore. In his refusal to accept charity from his mother, there is no trace of pride, only a longing to be treated as an equal. In moments like these, ‘Big World’ challenges our assumptions of care, reminding us that good intentions, when not paired with trust and respect, can also suffocate.

Chunhe’s mother, portrayed with nuance by Tan Zhuo, is a complex figure. She is fiercely protective, yet blinded by her fears. Though her actions stem from love, they often translate into control. Her belief that Chunhe would be better off in a sheltered university is less about his safety and more about her anxiety that he might fail or be rejected by a world that does not easily accommodate people like him.

It is Chunhe’s grandmother, however, who becomes the film’s emotional anchor. Played with understated strength by veteran actress Xi Meijuan, she is the only person in Chunhe’s life who sees him as a full human being, capable of pain, humour, desire, and anger. Their terrace conversation, where they exchange insecurities—Chunhe about his future, and the grandmother about her relationship with her daughter and her journey—is handled with such care that it lingers long after the scene ends. In her, Chunhe finds both safety and validation.

In one of the more frustrating but painfully believable subplots, Chunhe forms a tentative bond with a girl named Yaya. Their time together is brief but meaningful for Chunhe, who mistakes her kindness for romantic affection. The turning point arrives when she abruptly leaves, using the excuse of needing to use the washroom, only to wave him goodbye from a distance.

This scene was difficult to watch. It wasn’t the rejection itself that felt cruel, but the lack of honest communication. Her failure to clarify her boundaries earlier only added to the hurt. It left me wondering: If she had been more honest, would it have hurt more or less? And more importantly, why do we so often assume that people with disabilities do not understand or deserve transparency in emotional relationships?

The dream sequences in ‘Big World’ are not merely cinematic flourishes but psychological windows into Chunhe’s hopes. In the short scenes, we see him walking confidently, speaking fluently, and being embraced as one of the crowd. These dreamscapes aren’t loud or over-dramatic but effectively contrast with his lived experience. They make you ache not because Chunhe dreams of being someone else but because he dreams of a world where he is treated the same.

Jackson Yee’s performance as Liu Chunhe deserves all the attention. His portrayal is not mimicked, but lived. The physicality of his movements, the pauses in speech, the clenched jaw while trying to eat a piece of candy—these are not mere gestures. They are truths. The candy-eating scene in particular is as harrowing as it is ordinary. What for most people is a trivial moment becomes a symbolic battle of willpower for Chunhe.

The film also features a small but touching cameo from Gong Su, a man who has cerebral palsy in real life. He plays Chunhe’s friend, and it is revealed that the poem Chunhe gives to the girl (Yaya) is written by Gong himself. This casting decision adds layers of sincerity and avoids the common trap of able-bodied actors speaking for people with disabilities rather than with them.

One of the most powerful aspects of ‘Big World’ is that Chunhe does not get what he wants easily. There are no grand moments of victory. Everything he earns, he earns slowly, painstakingly, whether it’s the salary from a modest job or an acceptance letter from a regular university. That he chooses to work, to save, to apply on his own—despite his mother being against it—is what makes him inspiring.

In this era, where many students my age still rely on their families for financial, emotional, and academic support, Chunhe stands out not as a hero but as someone determined to live truthfully. That he does so with cerebral palsy only magnifies, not the hardship, but the commitment.

The film’s final scene, where Chunhe and his grandmother finally acknowledge each other’s truths and let go of their burdens, is both restrained and redemptive. There is no dramatic music, no tearful hugs. Just a quiet acceptance that they have both, in their own ways, done their best.

‘Big World’ is not a perfect film, but it is an important one. It doesn’t ask for pity, and it doesn’t glorify pain. What it does, instead, is challenge its audience to confront their own assumptions. It asks: when life is riddled with challenges, can love and kindness really make a difference?

The answer it offers is quiet but clear: yes, if we listen more and judge less.

At the end of the movie, I thought of all the caregivers, mothers, grandmothers, friends, and teachers who choose patience over panic, faith over fear. And I thought, too, of young people like Chunhe—those who want only what most of us take for granted: the chance to try.

Big World

Director: Yang Lina

Starring: Jackson Yee, Diana Lin, Jiang Qinqin

Duration: 131 minutes

Language: Mandarin

Available: Netflix

Year: 2024

10.83°C Kathmandu

10.83°C Kathmandu