Culture & Lifestyle

‘Photography and research are essential for public discourse’

Gérard Toffin and Prasant Shrestha have been working together since 2010 to document the changes ancient town of Panauti has witnessed over the years. The duo is now back with a photography book, ‘Panauti: Past-Present [1976-2020]’.

Srizu Bajracharya

Located 32 km east of Kathmandu, Panauti, for many, might seem like a town frozen in time. Unlike most Newa towns in neighbouring Kathmandu Valley, Panauti still retains its old-world charm.

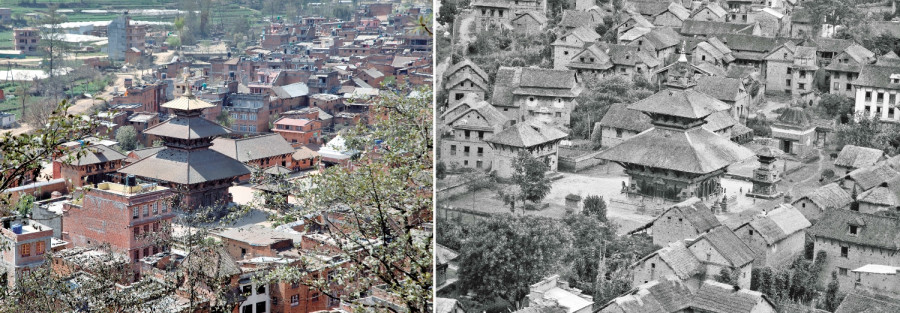

But a new photography book by social anthropologist Gérard Toffin and Panauti-based photographer Prasant Shrestha, ‘Panauti: Past-Present [1976-20]’, shows how this historical town has changed over the years.

Toffin’s photographs of the town from the late 1970s juxtaposed against Shrestha’s pictures of recent years portray drastic social and ecological changes the city has gone through.

Toffin, who first came to Panauti in 1976, spent years researching the town’s social and cultural heritage for the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS). In 2010, when Toffin was visiting Panauti, he met Prasant Shrestha, who was at the time interested in learning about his town's history and culture. In Toffin, Shrestha found a mentor, and since then, the two have worked closely to document the changes the town, they both love dearly, has seen.

In this conversation with the Post’s Srizu Bajracharya, Shrestha and Toffin detail the work they have put into the book and talk about Panauti’s past, present, and the importance of striking a balance between development and cultural preservation. Excerpts.

Gérard, what made you want to study Newa culture and towns?

I arrived in Kathmandu in 1970 and worked as a cultural attaché for the French Embassy in Nepal. Having studied anthropology, I was, at the time, thinking of pursuing my PhD studies and was interested in carrying out social anthropology research in Iran. But during my time in the French Embassy, I got interested in the social life surrounding me and learned Nepalbhasa to navigate the city.

Then one day, I came across Gopal Singh Nepali’s book about the Newa people. I was fascinated by his findings of the Newa people and their religious ceremonies and socio-cultural life. And I think that was what drew me towards studying Newa people. Before Nepali’s book, many foreign researchers focused more on places outside Kathmandu and other indigenous communities. And I was fortunate to have found the book just at the right time. It allowed me to focus my research on the Newa people, which few had done at the time.

So after my time in the French Embassy, I went to live in Pyangaun, Lalitpur, a small Jyapoo village. I spent eight months in the community and wrote my PhD research about their social and cultural life. Then when I came back again for CNRS’s research work, John Sanday (a British architect) introduced me to Panauti. And after that, I have always felt close to Nepal. I used to keep coming back to the country every year.

Prasant, growing up, were you always aware of Panauti’s rich cultural history?

I think, yes. Growing up, my grandparents used to tell me stories about our festivals, and we have festivals throughout the year in Panauti. This is why I have always had a high sensitivity to the importance of our culture.

And when I started collecting information about Panauti's culture and history, I kept coming back to Gérard's research about Panauti. I came to learn about my hometown’s history and people through his work. He was the researcher that helped place Panauti in the international arena. So, I had always wanted to meet him, and when he came to Nepal in 2010, I got to meet him and we got along well. Eventually, I became a resource person for his research work. He would ask me to find information and take photos of people and places. But while digging for information for him, I found myself becoming more appreciative of our town’s history and culture.

What do you think are some of the significant changes that Panauti has seen over the years?

Gérard: Panauti has changed a lot in these years, especially its traditional Newa architecture and inhabitants' lifestyle. When I first came to the town in 1976, the town's Newa architecture was very distinct and the people's traditional way of living was very much intact. The local marketplace was located in the heart of the city, but now it has been relocated to the city's entrance. In those days, the majority of the town's residents were Newa people, but today, there are diverse communities. A lot of modern houses have cropped up in the area. While economic development indeed has arrived, there are a lot of aspects that have been overlooked in the process. Today, the agricultural fields are barren. However, it’s not all negative. I see the Newa people, the natives of the place, more concerned about their culture and heritage as more development ensues. So, both good and bad changes have come to Panauti.

Prasant: Over the years, culturally and in terms of the place’s identity, Panauti has become more and more prominent as a historical town. When it comes to preserving culture and heritage, the local government is quite involved as well.

Over the years, the town has seen a lot of changes. Our rivers are more polluted than ever. Since prices of lands have reached sky-high, many farmers have sold their agricultural lands, and big buildings have cropped up on these lands. I fear that these changes will undermine our communal and cultural ways of living.

So, how did this book happen?

Prasant: This book was not originally in our plan. In 2019, to show the changes Panauti has seen over the years, Gérard and my photos of the town were exhibited at Alliance Française de Kathmandu. The then French Ambassador to Nepal François-Xavier Léger, having been to our exhibition, asked if our work could be brought out in a book format. I was overwhelmed by his admiration for our work. Over the years, the French Embassy in Nepal has been part of many restoration projects in Panauti.

Gérard and I soon started discussing how to go about the book, and he made it clear from the get-go that the book cannot just be about the before and after photographs but should also be able to give comprehensive information about Panauti and insight into urbanisation’s impact on the town's cultural heritage.

How do you think such books and research help preserve cultures and traditions?

Prasant: The more we discuss and bring to people’s attention what our culture means for our society, the more people will realise their importance. Such books are not just for people who are interested in culture but also to make general people aware of one's culture and the need to preserve them. These kinds of books encourage people to pause and rethink what development means. Once you read the book, you will be unable to unsee development's impact on Panauti's environment, culture, and tradition. The revival of traditions like Devi Pyankhan and the Kumari tradition is, in some ways, contributed by the awareness emphasised through the cultural discourse of research studies.

Gérard: I think it is essential that we learn about the diversity in the world, and books like these help in that knowledge-sharing. My interest in anthropology was ignited by my interest in learning more about the world's diverse social and cultural life, and I think studies like these help see how the world has changed and what we need to focus on. I decided to study and research Panauti’s culture and traditions because I was intrigued by how people’s cultural life is still connected to their communal living and social life; society here is more interconnected, which is not the case in Europe.

What do you hope for the photography book to do?

Prasant: For me, this book shows how photography and research are essential for public discourse. Gérard’s photos of Panauti from 1976/77 and my pictures of the town in recent years show what we have lost in these years. Many people will be bound to think of the positive and negative aspects of the changes that have swept the town and what that means for us as a society.

Gérard: I hope this book will urge people and the authorities to consider preserving what needs saving and rethinking the development Panauti has seen over the years. I see our book as a step forward to that thinking.

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)