World

A Russian graveyard reveals Wagner’s prisoner army

A rapidly expanding cemetery in a southern Russian village offers insight into the convicts who are fighting - and dying - for the secretive mercenary army of Wagner Group.

Reuters

Late last summer, a plot of land on the edge of a small farming community in southern Russia began to fill with scores of newly dug graves of fighters killed in Ukraine. The resting places were adorned with simple wooden crosses and brightly coloured wreaths that bore the insignia of Russia’s Wagner Group - a feared and secretive private army.

There were around 200 graves at the site on the outskirts of Bakinskaya village in Krasnodar region when Reuters visited in late January. The news agency matched the names of at least 39 of the dead here and at three other nearby cemeteries to Russian court records, publicly available databases and social media accounts. Reuters also spoke to family, friends and lawyers of some of the dead.

Many of the men buried at Bakinskaya were convicts who were recruited by Wagner last year after its founder, Yevgeny Prigozhin, promised a pardon if prisoners survived six months at the front, this reporting showed. They included a contract killer, murderers, career criminals and people with alcohol problems.

For months, Wagner has been locked in a bloody battle of attrition to take the towns of Bakhmut and Soledar in Ukraine’s eastern Donetsk region. Western and Ukrainian officials have said it is using convicts as cannon fodder to overwhelm Ukraine’s defences. Toughening sanctions on Wagner this month, White House national security spokesman John Kirby branded the group “a criminal organisation that is committing widespread atrocities and human rights abuses.” In a short open reply to the U.S. government, Prigozhin asked Kirby to “please clarify what crime was committed” by Wagner.

Videos and photographs of the graves first appeared on social media channels in the Krasnodar region in December. Reuters geolocated these images to the Bakinskaya cemetery and reviewed satellite imagery of the site from Maxar Technologies and Capella Space. Satellite pictures show that the Wagner plot was empty in the summer, had three rows of graves by the end of November and was three-quarters full by early January. Virtually the entire plot was used by Jan. 24.

Local activist Vitaly Votanovsky, who took the first pictures and has documented soldiers killed in Ukraine and buried in Krasnodar region graveyards, told Reuters he observed a truck delivering bodies to the cemetery. He said gravediggers told him the bodies had come from the Russian city of Rostov-on-Don, close to Russia’s border with Donetsk region. When Reuters visited the cemetery in January, fences and security cameras were being installed around the plot and another burial was underway.

Russian state-owned news agency RIA Novosti published footage in early January of Prigozhin visiting the cemetery, crossing himself and laying flowers on one grave. He told local media that the men buried there had expressed a wish to be laid to rest at a Wagner chapel outside the nearby town of Goryachiy Klyuch, rather than having their bodies returned to relatives. The Bakinskaya plot was provided by the local authorities, he said, after the chapel ran out of space. In 2019, Reuters reported on the existence of a Wagner training camp in the village of Molkino, around 5 miles (9 km) from Bakinskaya.

Of the 39 convicts Reuters identified, 10 had been imprisoned for murder or manslaughter, 24 for robbery and two for grievous bodily harm. Other crimes included manufacturing or dealing in drugs and blackmail. Among the convicts were citizens of Ukraine, Moldova, and the Russian-backed breakaway Georgian region of Abkhazia. Wooden markers on their graves at Bakinskaya and three nearby cemeteries show the men perished between July and December 2022, at the height of the battle for Bakhmut.

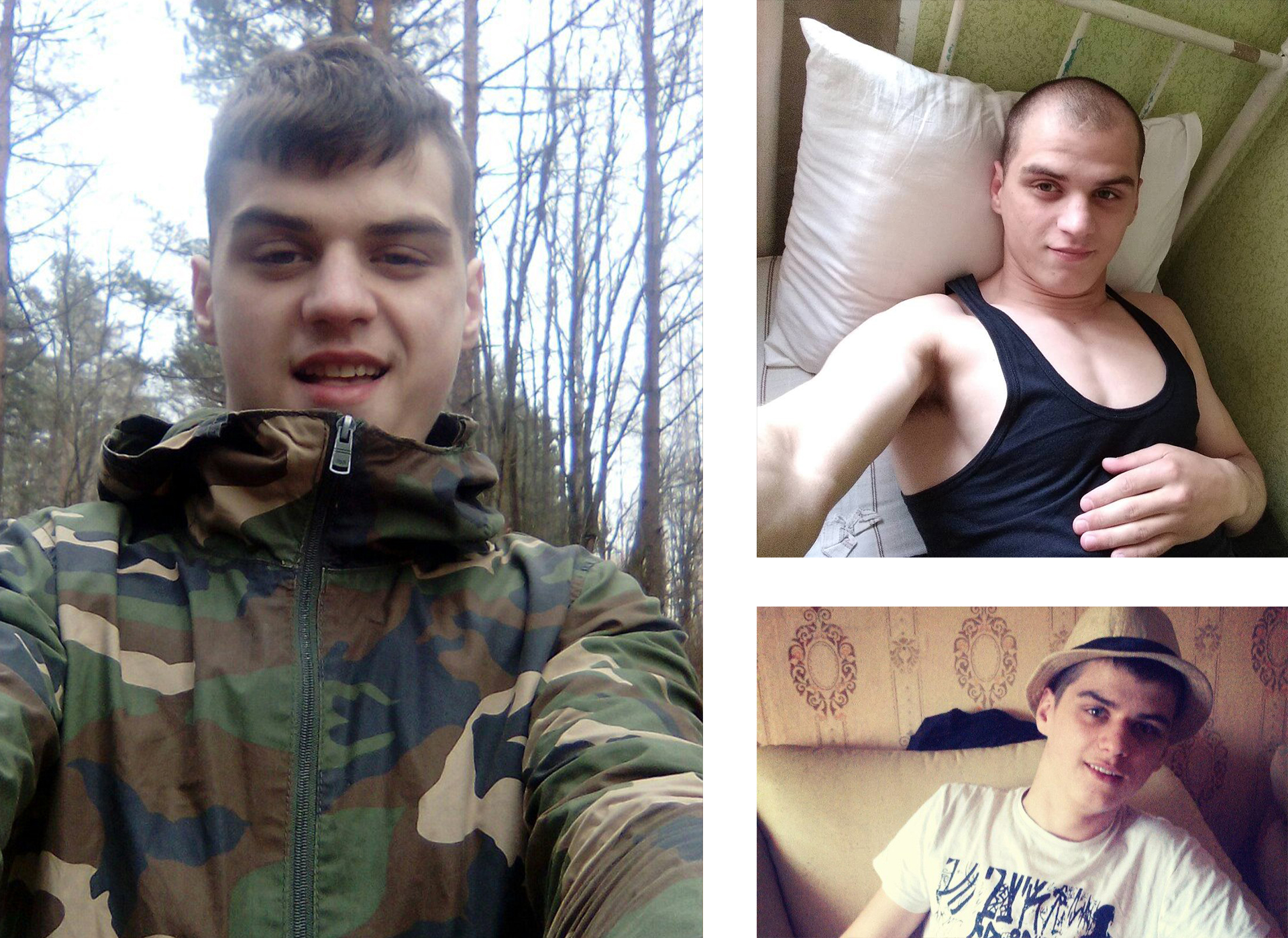

One of the youngest, buried at the nearby Martanskaya cemetery, is Vadim Pushnya. He was just 25 years old when he died on Nov. 19. Pushnya was imprisoned in 2020 for burgling garages, a beer shop and a cement factory in his hometown of Goryachiy Klyuch, close to the Wagner chapel. The birthdate on Pushnya’s grave matches the date given on his social media accounts and in court records.

The oldest, Fail Nabiev, was serving one-and-a-half years for burglary in Ivanovo region’s Penal Colony No. 2, 200 miles northeast of Moscow, at least his second such prison spell. He had been convicted in May 2022 by a court in the picturesque tourist town of Suzdal of stealing a string trimmer and a sanding machine valued at a total of 5,500 roubles ($80) from a garage. According to his simple wooden grave marker, emblazoned with an Islamic crescent moon, Nabiev died in October, less than five months after being sentenced. He was 60.

Nabiev’s common-law wife, Olga Viktorova, confirmed to Reuters that Nabiev had been killed while serving with Wagner in the military campaign in Ukraine. She said that her husband had been nearing the end of his prison term, and that he had substantial credit card debts that she was now left to pay. She said she did not know that her husband had joined Wagner until after his death. Russian independent news site iStories has reported that Prigozhin visited Penal Colony No. 2 to recruit fighters in August. Reuters couldn’t independently verify the report.

“He always had crazy ideas. An incorrigible optimist,” Viktorova said. Nabiev probably “thought that he’d take a quick trip to Ukraine and earn some money.”

The Kremlin, Russia’s Defence Ministry and Russian prison authorities did not reply to questions for this article. The Russian government has in the past praised the “courageous and selfless actions” of Wagner fighters. Wagner’s founder Prigozhin, who also didn’t comment, has said previously he is giving convicts “a second chance at life.”

Though Reuters was unable to confirm where exactly the men died, the mother of one said that her son was killed in the Donetsk region. The social media accounts of several others also indicate that they were in Ukraine prior to their deaths.

Since the beginning of Russia’s war in Ukraine, the previously secretive Wagner and founder Prigozhin have assumed an increasingly public profile. In the past, Wagner fighters have deployed to Syria, Libya and the Central African Republic in support of Russia’s allies. Prigozhin, known in Russia as “Putin’s chef” because of his Kremlin catering contracts, consistently denied any links to Wagner. Then, last September, he confirmed he founded the private army, which he described as a “group of patriots.”

Since then, Prigozhin has repeatedly visited the frontlines in eastern Ukraine, while also criticising Russia’s military leadership and some senior officials, and personally spearheading a drive to recruit fighters from Russia’s sprawling penal system.

According to a regular report published by the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service, Russia’s penal colony population decreased by about 8% from 353,210 in August to 324,906 in early November, the largest drop in more than a decade. The report gave no reasons for the sudden, sharp decline, which coincided with the beginning of Wagner’s prison recruitment push. The Federal Penitentiary Service did not reply to detailed questions for this article.

Last month, Reuters reported that the U.S. intelligence community believes that Wagner had approximately 40,000 prisoner recruits deployed in Ukraine as of December, accounting for the vast majority of Wagner personnel in the country. Wagner has not commented on the figure or provided any information on fighter numbers. In a Jan. 14 video message, Prigozhin described Wagner as a fully independent force with its own aircraft, tanks, rockets and artillery. It is “probably the most experienced army that exists in the world today," he said.

Violent offenders and alcohol abusers

Some of the convicts identified by Reuters were violent offenders who had spent much of their adult life in prison or were facing long sentences. Court papers reviewed by Reuters also portray men who had struggled with alcohol problems. The names of some others are on banking black lists, suggesting personal financial troubles.

Their lives bring into bleak focus the realities of Russia’s criminal underclass. Wagner founder Prigozhin in December told Russian news site RBC that he is giving convicts an opportunity “to redeem themselves.” In January, he appeared alongside the first group of fighters to be pardoned, having survived their stints in Ukraine. A few weeks later, he wrote an open letter to the speaker of Russia’s parliament, Vyacheslav Volodin, asking him to criminalise any actions or publications that discredit Wagner fighters and to outlaw public disclosure of their criminal pasts. He wrote that those “who are risking their lives every day and dying for the Motherland are being portrayed as second-class people, stripping them of the right to atone for their guilt.” Volodin did not reply to Reuters’ request for comment.

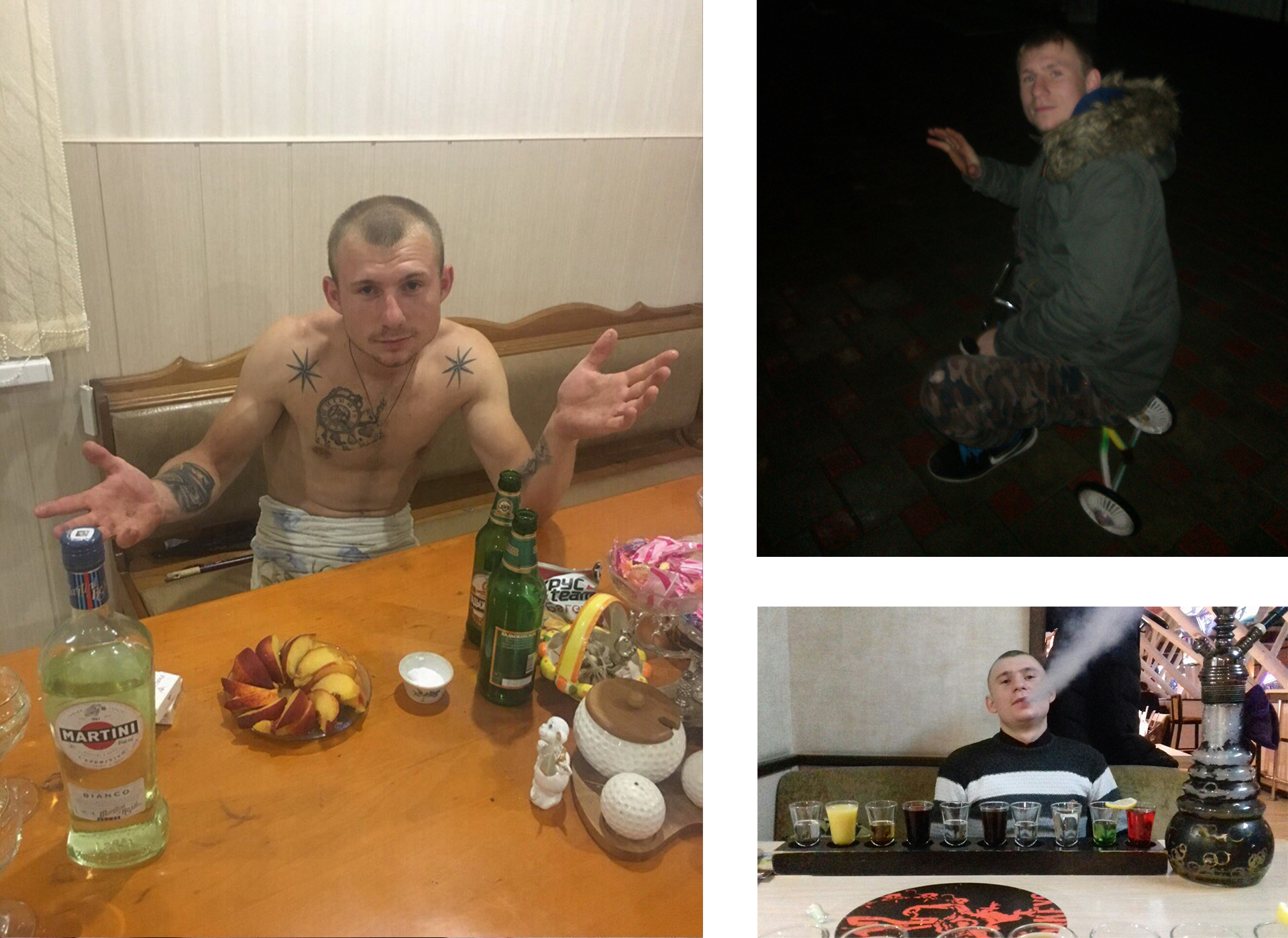

Among the prisoners identified by Reuters was 43-year-old Anatoly Bodenkov. He was serving a 16-year sentence after his conviction as a contract killer, court papers show. According to a local news report on the case, in 2016 Bodenkov murdered a local real estate agent in the northern city of Kirovo-Chepetsk with a sawn-off shotgun for 400,000 roubles ($5,720). The grave marker says Bodenkov died on Nov. 27, 2022. It doesn't say where.

A second prisoner, Viktor Deshko, 40, was sentenced to 10 years for a murder in 2021, according to court documents and local media reports. He cut a woman’s throat during a drunken argument over money in the forests near the mining town of Shakhty, close to the border with the Russian-controlled Donbas. Court documents describe Deshko as “an aggressive person, given to abusing alcohol.” He was on probation at the time of the killing, having previously served three and a half years for assault with a deadly weapon.

For Bodenkov and Deshko, the full names and dates of birth on the grave markers matched their social media and court records. Reuters was not able to contact friends or family of the two men, and their lawyers did not reply to requests for comment.

A third man, Vyacheslav Kochas, was sentenced to 18 years in prison by a St. Petersburg court for murder and armed robbery in 2020, when he was 23. According to Russian court documents, Kochas and another man burst into the apartment of an acquaintance while drunk in an attempted robbery. He beat the acquaintance and a female victim unconscious, using an iron and a metal clothes horse. Kochas then set fire to an item of clothing and threw it at the unconscious man. Much of the apartment was gutted by the fire, and the man succumbed to his wounds two days later.

Photographs of Kochas on social media show a baby-faced man. In some he is embracing an unidentified young woman. Kochas’ profile on VKontakte, Russia’s Facebook equivalent, now reads: “Killed in the Donbas.” Kochas’ grave marker at Bakinskaya gives his date of death as July 21, shortly after his 25th birthday and in the earliest days of Russia’s push towards Bakhmut.

Kochas’ lawyer, Stepan Akimov, described his former client as “a really ordinary guy” whom he said had been unfairly convicted. The last he heard from Kochas was a text message after his appeal failed, thanking Akimov for his help. Akimov learned from Reuters that his ex-client had joined Wagner.

“I can imagine, given the length of his sentence, and how young he was, it seemed to him a way to go free,” said Akimov. “When a prisoner has a double digit sentence, here they’re offering release in six months. Apparently, Vyacheslav thought this offer was a way out.”

Reuters was unable to reach Kochas’ surviving relatives.

Russia has one of the world’s largest prison populations per capita. Mark Galeotti, author of The Vory: Russia’s super mafia, a book on Russia’s criminal and prison cultures, says the potential appeal of Wagner to inmates is wider than just a bid for clemency. Service with Wagner, he said, offers pride and a sense of purpose to convicts with few prospects after release, people who have spent time in a prison culture suffused with “a very strong Russian nationalist tinge.”

“Yes, this will give you the chance to get out of prison, but also it gives you the chance to actually be someone,” said Galeotti. “This is a way in which actually Wagner can appeal to people who definitely are, or believe themselves to be, marginalised, outsiders, losers in some way in the system, and gives them the chance to think of themselves as becoming winners.”

At least one of the men buried at Bakinskaya concealed their criminal record and prison time from loved ones.

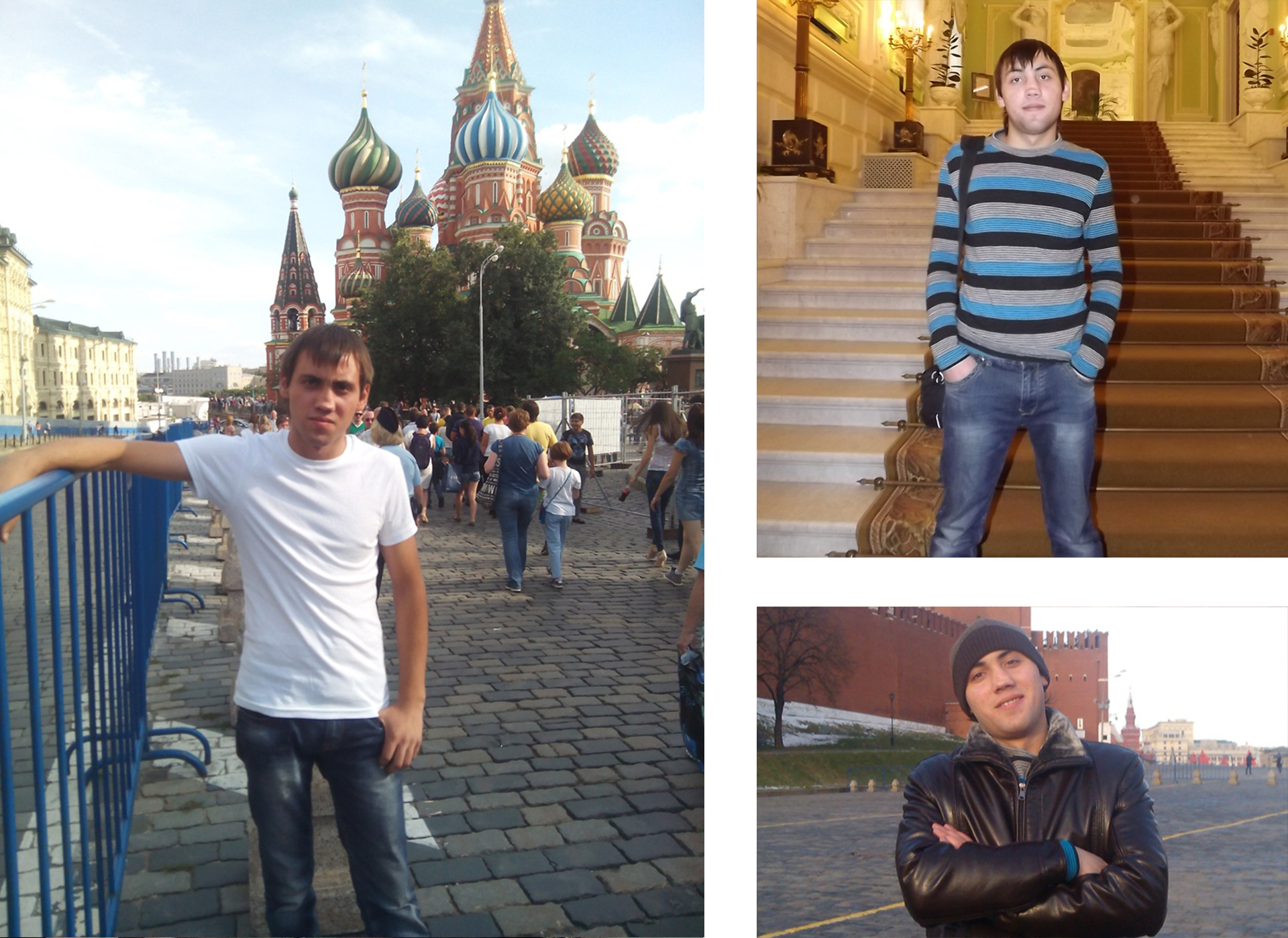

For over half a decade after she got married and left her hometown of Luhansk in eastern Ukraine, Svitlana Holyk believed that her brother Yury Danilyuk was working somewhere in the far north of Russia. The two Ukrainian-born siblings had few living relatives and rarely spoke after Russian-backed proxies seized their home city in 2014, she said. Svitlana knew only that her brother travelled regularly for work to the Russian border city of Bryansk, 500 miles (800 km) away.

But while Svitlana was building a new life in the Ukrainian city of Dnipro, Yury was using social media to subscribe to pro-Russian groups supporting the Donbas separatist insurgency, his online activity shows. In 2016, having been out of touch for a year and a half, Yury told his sister that he had moved to Russia’s Arctic north. She said his messages were short, and he said little about his life.

“I suspected then that something had happened, that he might have some troubles that he did not want to or could not talk about for some reason,” she told Reuters, speaking Ukrainian, in a telephone call from Dnipro. The city is now a major logistics hub for the Ukrainian army fighting in the Donbas, and a constant target of Russian missiles.

A close friend of Yury Danilyuk spoke to Reuters on condition of anonymity. The friend said that Yury lied to his sister, whom he deeply loved, to avoid upsetting her with news of his imprisonment. In reality, he had been sentenced in 2016 to nine years and eight months in prison on drugs charges. The two men were incarcerated together in Krasnodar region’s Penal Colony No. 6.

The friend said he last spoke to Yury in September 2022 and heard later that month from other inmates that Yury had joined Wagner. Olga Romanova, a prisoners-rights activist with the Russia Behind Bars watchdog group, told Reuters that Yevgeny Prigozhin has visited Penal Colony No. 6 to recruit inmates on two separate occasions. Reuters couldn’t independently verify these visits.

The friend said that during his time in jail, Yury fell in with a faction of prisoners who refuse to cooperate with prison authorities on principle – a common phenomenon in Russia’s penitentiary system. That meant Yury forfeited the chance of early release for good behaviour. He said Yury’s decision to join Wagner was motivated by the knowledge that he would likely otherwise serve his long sentence in full.

According to his grave, Yury Danilyuk died on Nov. 30, 2022. He was 28.

Danilyuk’s sister, Svitlana, said she had known nothing of her brother’s prison sentence, service with Wagner, and eventual death during Russia’s war against the country of their birth until contacted by Reuters journalists. Holyk said: “The fact that Yury died I learned from you. I re-read your message several times when you wrote to me. Somehow I couldn't believe it.”

The inmate friend recalled Yury as a fierce patriot of his native Donbas, with a passion for cars. “I blame it all on him not wanting to cooperate with the prison authorities,” the friend said. “If he had agreed, he’d be alive. But he refused, so he’s a fool.”

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu