Valley

Bhutanese refugee issue resurfaces after provisions dry up

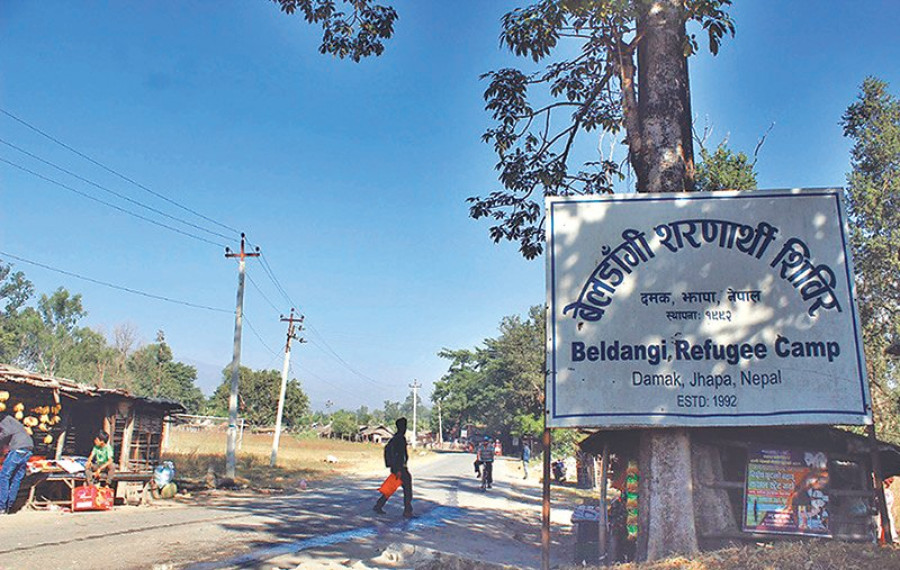

Nepal faces renewed diplomatic and internal challenges in coping with 6,500 Bhutanese refugees who remain in two camps in Jhapa as the World Food Programme suspends its 26-year-old support and the third country settlement scheme draws to its close.

Anil Giri

Nepal faces renewed diplomatic and internal challenges in coping with 6,500 Bhutanese refugees who remain in two camps in Jhapa as the World Food Programme suspends its 26-year-old support and the third country settlement scheme draws to its close.

Now the onus lies on the Nepal government to renew talks with the Bhutanese government for sending back the refugees after their last batch adopts third country resettlement soon. A total of 110,000 Bhutanese have been resettled in the United States and Canada, among other Western countries, so far.

When the WFP stops food aid from December-end as announced, Nepal will have to manage food and other supplies essential for them until the Bhutanese refugee issue is settled permanently.

The UN food agency is going to extend its cash-for-food scheme for all the refugees remaining in the camps by three months and some socio-economically vulnerable refugees numbering not more than 700 by six months.

The UN refugee agency and some Western countries are pressing for local integration of the refugees, an option Nepal has rejected outright. Citing a sizeable ageing population not interested in third country resettlement and those with local connections such as marriage, jobs, and education, the donor community has been pitching the idea of locally integrating the refugees. In fact, they are already laying some groundwork quietly.

“We’ve communicated our position clearly that there is no possibility of locally integrating the refugees,” Foreign Minister Pradeep Gyawali said.

“The refugee agency started third country resettlement after a one-and-a-half dozen failed ministerial-level talks with Bhutan. The UN agencies had promised to repatriate those left after third country resettlement,” Gyawali added. “Now they should push Bhutan for taking back its citizens because Nepal cannot shoulder their burden indefinitely as it is not a party to refugee convention but had hosted them on a purely humanitarian ground.”

In view of the immediate challenges facing the refugees, the Home Ministry has written to the Finance Ministry to suggest alternatives. “We have written to the Finance Ministry to meet their requirements for the short term. This is not a permanent solution and the Nepal government cannot sustain it for long. The only solution is repatriation of the refugees and we need to renew talks with Bhutan,” Home Ministry Spokesperson Ram Krishna Subedi told the Post.

In an email response to the Post, the WFP that oversees food supplies at the refugee camps, said: “According to our communications with MoHA/National Coordination Unit for Refugee Affairs [NUCRA], we believe that the Government of Nepal is committed to providing short-term and long-term solutions to the refugees’ problems.”

Government officials said that several Western countries and the UN agencies concerned with the Bhutanese refugees have been pushing for local integration as they are not much hopeful of successful talks with Bhutan on refugee repatriation.

Officials, however, are optimistic about the refugees going back home eventually since two Nepali-speaking politicians have been appointed Cabinet ministers in Bhutan recently.

Two government officials objected to some of the activities of by the UN agencies and donors at the refugee camps as preparation for local integration in the name of birth registration, income generation, livelihood support, health care and education.

An official at a UN agency clarified that these were alternative measures to ensure better living conditions in the camps—not a move to support local assimilation of the refugees. But there have been persistent calls from refugee hosting countries for Nepal to permanently settle the Bhutanese.

The UN food agency claims to have spent more than Rs10 billion in the last 25 years on the provisions.

The WFP told the Post that it has stopped food aid to the remaining refugees and communicated its decision to the Home Ministry citing that its priority has shifted to other countries. The WFP would transition out of its food assistance programme in Nepal for refugees from Bhutan starting in January 2019, the WFP stated. “From December, WFP will disburse the last remaining funds as a ‘close-out package’ ensuring that all refugees receive funds for three to six months, with priority given to the most vulnerable.”

After the transition, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees would continue to provide targeted cash assistance for the most socio-economically vulnerable refugees to meet some of their basic needs, the WFP said.

22.7°C Kathmandu

22.7°C Kathmandu