Arts

Bringing unnoticed stories to life on paper

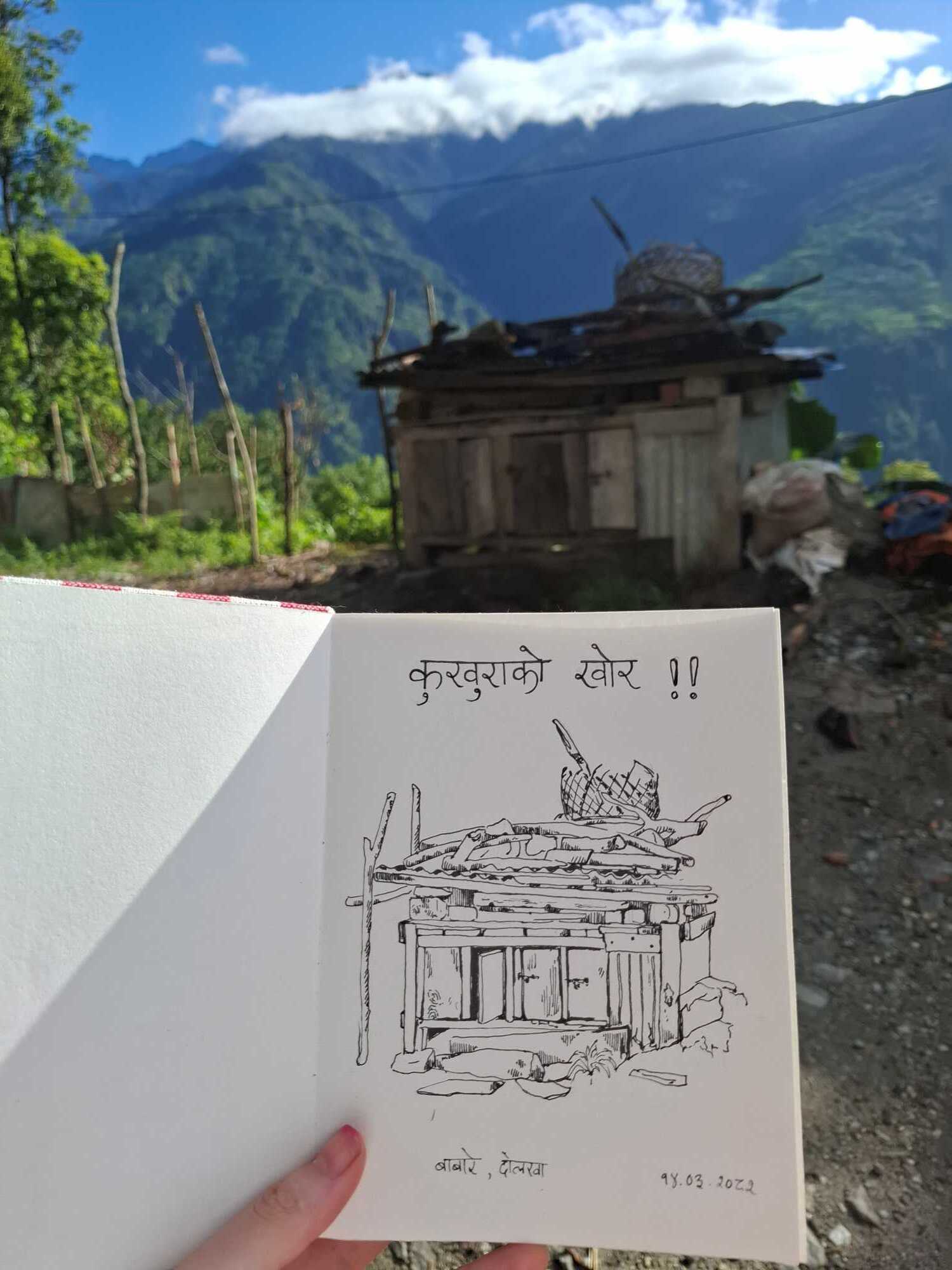

From chicken coops to old Patan houses, Pragya Mainali’s live sketches open a window to the beauty of everyday life.

Anish Ghimire

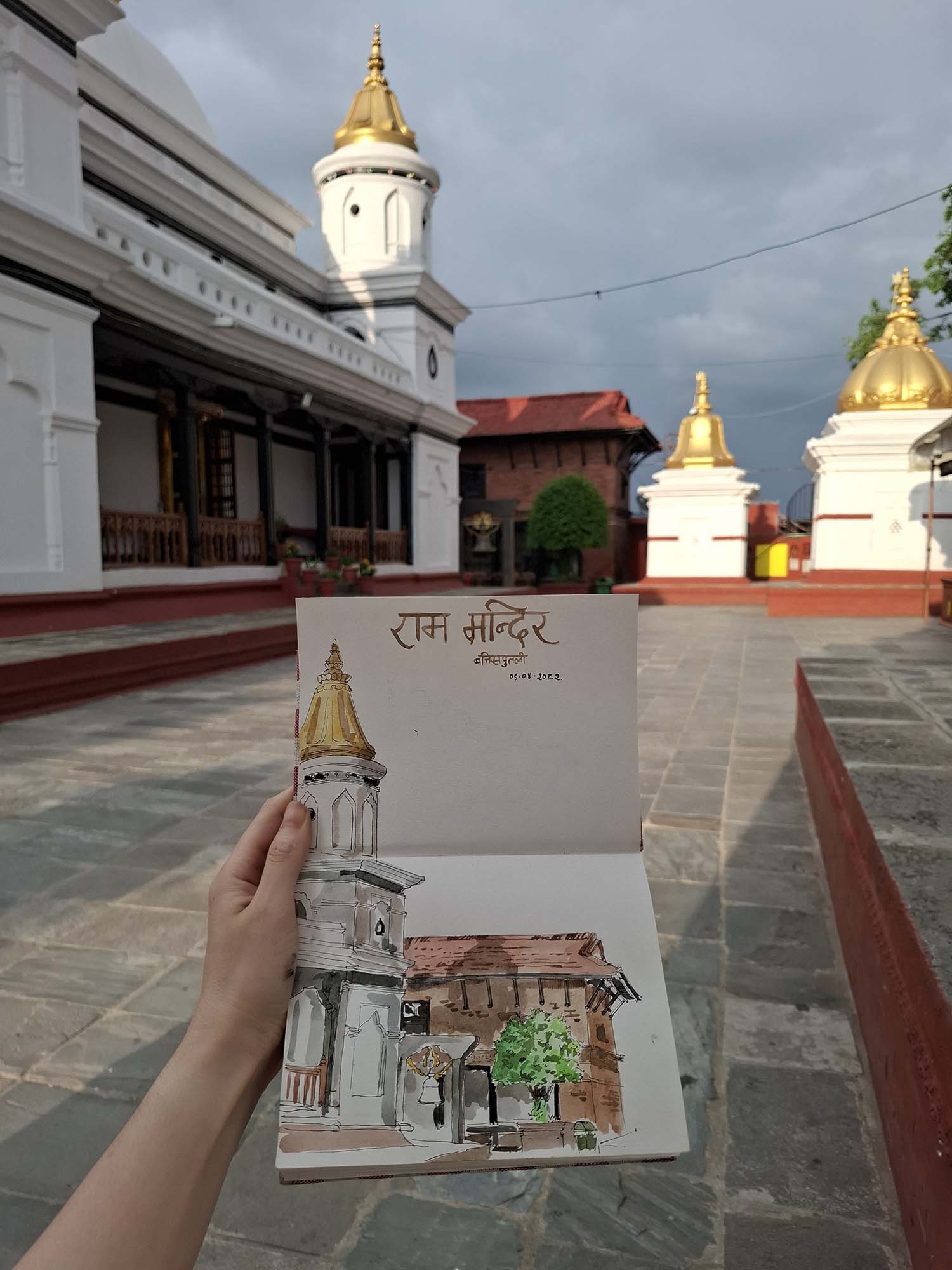

For Pragya Mainali, everyday life carries stories that aren’t so ordinary as we make them out to be. The everyday grocer, a chicken coop, a rusted tap outside a village home, and a century-old building in a crammed settlement in Patan—she captures them with her hand, forever immortalising them in her sketchbook.

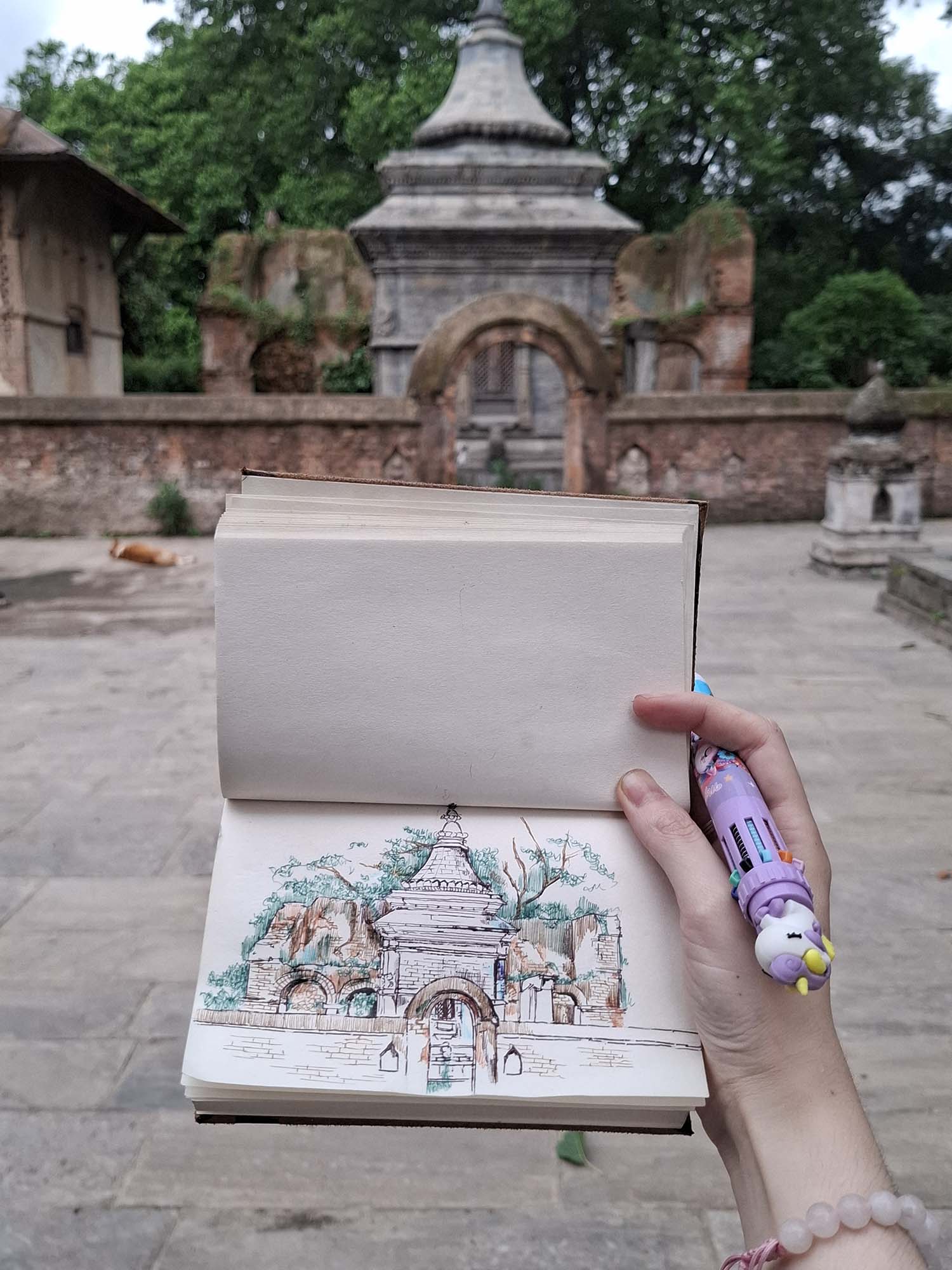

For many of us, there is little time to pause and notice the small details that make up our world. We walk past the intricately carved pillars of a pati (rest house) in an old Newa settlement. We do not look twice at classical windows that demand attention, and we pseudo-look at towering architecture, sitting grandly, through our phone’s camera. But Mainali wants to jot down these missed details. She finds a spot, sits down and begins to sketch as curious onlookers surround her.

Fresh out of architecture school, Mainali has been drawing since she was a little girl. But it was no “this is what I want to do with my life,” kind of whim. She started casually, and her inspiration was just doing it for the sake of it. Later, in school, ambushed by textbooks, she had to stay away from artistry. When she finished A-levels, she wanted to study economics abroad, but the stars got in her way. (That’s correct)

After studying Mainali’s birth chart, an astrologer advised against it, warning that moving abroad could put her life at risk. So, encouraged by her father, she stayed back in the city of temples and studied architecture instead.

During the course, she and her classmates were required to enrol in a building conservation studio. This allowed her to visit the old settlements of Patan, where she began sketching historic houses, capturing their rich cultural and architectural grandeur.

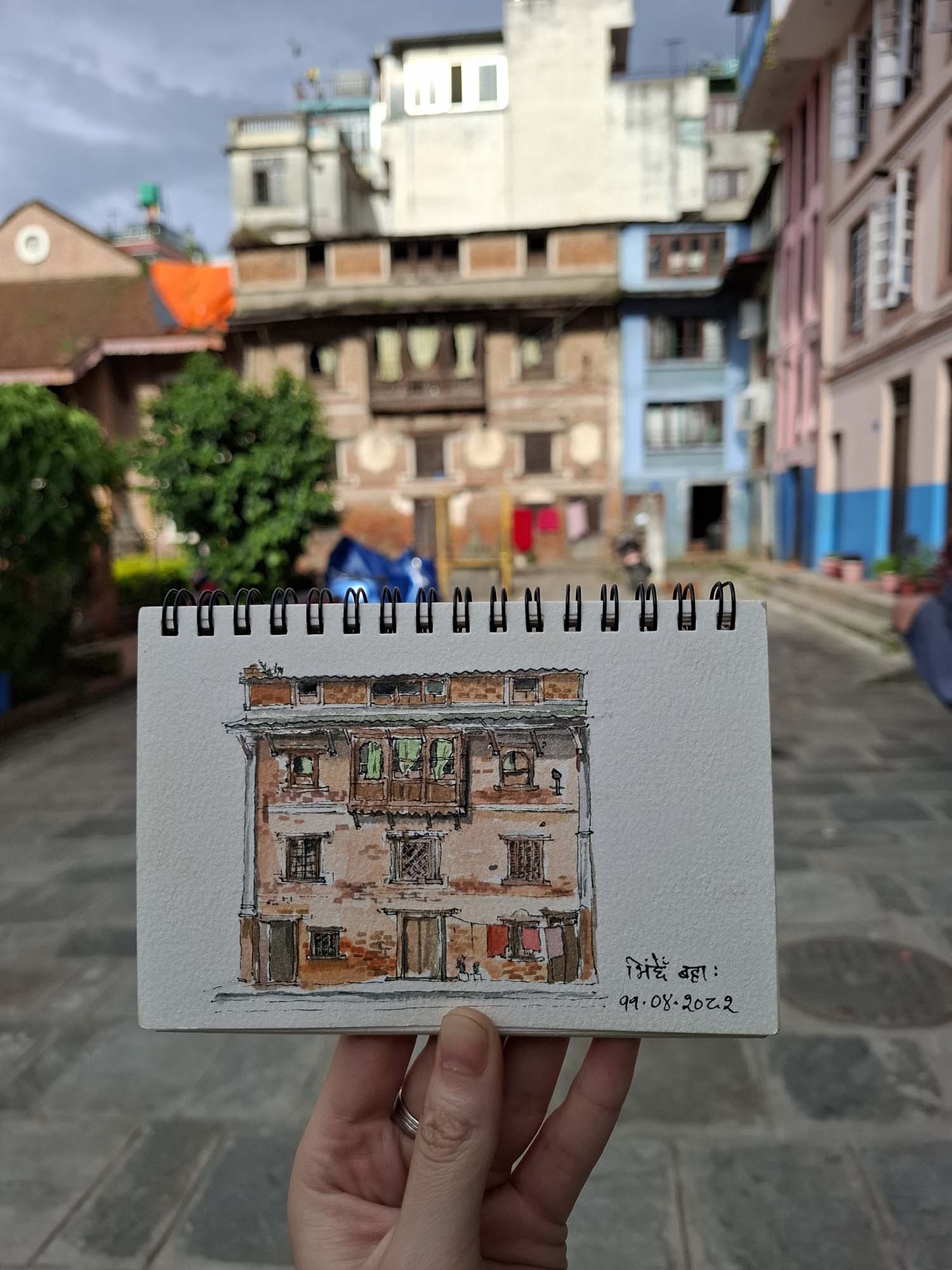

Watching Mainali sketch, it’s clear that drawing houses takes a hand as steady as a rock, so the lines come out straight as arrows. “I learned to draw straight lines in architecture school,” she tells me as we sit at one of the public benches in the square of Bhinchhebahal, Patan. In the afternoon, the square, surrounded by colourful houses built by architects of many styles—remains quiet. But in the evening, just after school lets out, children fill the space, enjoying a rare open area in a city that grows more crowded with each passing night.

Much like in Test cricket, where coaches tell batsmen to keep their hands soft, artists warm up by drawing random lines to loosen their hands and make their sketches more free-flowing. This helps Mainali capture the ebbs and flows of rusted jasta pata (corrugated metal sheets) on old buildings. Having soft and steady hands allows many artists like her to draw fine details with ease.

In many of her sketches, Mainali treats buildings not as mere monuments but as structures that breathe. In ‘Bhinchhe Bahal’, an old house comes alive—curtains sway in the wind, windows sit slightly ajar, clothes dry in the sun, and well-tended plants grow on the roof.

To capture such details, an artist must sit in one spot for hours, observing how light falls, how walls weather, and how curtains sway. The drawing doesn’t just capture a scene or a subject—it captures a moment in time. “There are stories everywhere—even in the cracks of old houses and the rusted metal in old jeeps,” she says. To find such stories, she often sketches in public, setting up in busy squares or quiet alleys. Unlike sketching in solitude, public sketching can feel like a performance in itself. As the artist draws, locals gather, observe, and sometimes share stories.

While visiting Dolakha for a project, Mainali noticed a chicken coop and decided to sketch it. As she sat down to draw, an intrigued stranger approached and struck up a conversation. Soon, he was sharing stories about his working days in Dubai. Now, every time she looks at that sketch, she’s reminded of that conversation. “This is what I mean when I say I want to sketch stories, not just objects,” she says.

During the same time, while sketching houses in Dolakha, homeowners often invited her for tea and shared life stories. In this way, sketching becomes an act of community engagement, not just a solitary process.

Mainali describes herself as an ambivert, yet feels no awkwardness when doing public sketches. She owes much of her confidence to Urban Sketchers Kathmandu. USK Kathmandu is the official Nepal chapter of the global Urban Sketchers (USK) community—a non-profit that brings together people who love to draw from life, on location.

The USK Kathmandu organises regular sketch meetups across the Kathmandu Valley, from temples and tea shops to busy streets and quiet courtyards, where the participants draw what they see, feel, and experience in the moment. So far, they’ve held 37 meetups, bringing together a growing community of more than 200 sketchers from all walks of life. “I’ve met such amazing and like-minded people through this community,” she says.

Alongside Urban Sketchers Kathmandu, Mainali has built a strong online community. She has over 13,000 followers on X (@Lorem Ipsum), where she shares her artwork, favourite art supplies, and everyday inspirations. Her active online presence has also brought financial support, with buyers, particularly from abroad—reaching out through social media to purchase her work or request commissions.

Whether she’s sketching the nooks and crannies of Kathmandu, drawing random inspiration from Pinterest, or sketching live with like-minded people, Mainali plans to keep sketching and keep capturing the world in her sketchbook.

12.12°C Kathmandu

12.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=200&height=120)