Valley

[Constitution special] How we arrive at a compromise?

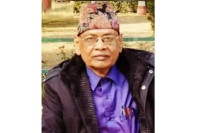

The CPN-UML’s Chief Whip reflects on the milestones that led to the creation of the statute![[Constitution special] How we arrive at a compromise?](https://assets-api.kathmandupost.com/thumb.php?src=https://assets-cdn.kathmandupost.com/uploads/source/news/2015/miscellaneous/20092015100103agni.jpg&w=900&height=601)

- Agni Kharel

After the first CA elections in 2008, all political parties took the rigid stance that they would stick to their election manifestos. No one was the least bit interested in reaching a compromise. This was one of the major reasons behind the previous CA’s failure to come up with a new constitution within the given timeframe. Over time, however, the parties realised that it was not possible to complete the constitution-writing process without recalibrating their positions. Beset by the legacy of the first failed CA, the parties began to discuss the possible solutions for and reasons that each party had adopted different positions regarding the contentious issues. We were careful not to repeat the mistakes of the first CA.

For example, the Maoists pushed for a directly elected president as head of government. We stood for having a directly elected prime minister, while the Nepali Congress insisted on a prime minister elected by the Parliament. We wanted to opt for a directly elected prime minister because we wanted to ensure a stable form of government. So we engaged in discussions on how to ensure stability within the parliamentary system. For this, we proposed the creation of a provision whereby a vote of no confidence could not be introduced within two years of a prime minister’s being elected and the requirement that an alternative candidate be proposed if such a motion were to be introduced. Also, it was proposed that a second vote of no confidence motion be not allowed at least within one year from the tabling of the first vote of no confidence motion. We all agreed on this issue, but the UPCN (Maoist)s continued to oppose the provision. Despite having disagreements on forms of government, the Maoist party agreed to push the constitution-writing process by registering a note of dissent.

The differences among the major political parties over federalism pushed the first CA towards failure. Although we managed to define the basis of federalism—capability and identity—there was not enough deliberation over federalism. The Maoists, the former rebels, who had emerged as the largest party in the first CA, failed to recognise that their fate was inextricably linked with the success or failure of the first CA. The party didn’t seem to be worried about the implication on its standing if the CA failed to deliver.

The parties had reached an agreement just days before the dissolution of first CA. But the Maoists party was not able to stick to the agreement.

The constitution we have now is a very progressive document. Of course any constitution will not be accepted by everyone. There are aspects of the constitution that I too don’t fully agree with. But since this constitution is a product of compromise, I think it will be durable.

To be sure, some of the political parties who had initially participated in the constitution-writing process walked out when the CA started voting on the constitution. But in terms of numerical strength, their presence in the Constituent Assembly was nominal in comparison to the number of CA members supporting the constitution. And if you look at all the constitutions that have been written by a constituent assembly, we have done fairly well.

We are ready to sit down and discuss with the parties that remain dissatisfied. Our political culture is such that any political party can easily sit down with other parties to hammer out the differences. We will start on a new course once the constitution is promulgated, and we are ready to hold discussions on genuine demands with all disgruntled parties and make the required changes to the constitution.

We must remember that the constitution can be revised. Except for provisions concerning Nepal’s territorial integrity and national interest, all other aspects of the constitution can be amended. We have incorporated republicanism and federalism too as amendable provisions of the constitution despite some skepticism in some quarters about whether these issues should be treated thus. The logic behind placing these issues in the amendable section is to enable it to be a durable document that can stand the test of time. Despite having so many good provisions, the constitution of 1990, for example, was not able to

meet that test. A constitution that can be amended is not necessarily a weak constitution; rather, such flexibility is a sign of strength. I believe this constitution is a dynamic document that will evolve in accordance with time and changing contexts.

(As told to Bhadra Sharma)

16.24°C Kathmandu

16.24°C Kathmandu