Madhesh Province

Some see cultural shift in vanishing clay tile roofs

Rising incomes from foreign jobs are tempting people to adopt modern housing, putting ‘Madhesh heritage’ at risk.

Santosh Singh

Ham Na Rahab Saiya Mati ke ghar me,

Paka Pitwaida balamuwa…

(I don’t want to live in a mud house, husband

Please build a concrete house for me)

The song by Bhojpuri singers Nisha Dubey and Arvind Akela tells a story of a woman who is asking her husband in a foreign land to send her money to build a concrete house. She no longer wants to live in a house with clay tile roofing.

The song topped the charts in Madhesh when it was released some two decades ago. A majority of the listeners related to the song since it depicted the condition of the settlements and homes of Madhesh at that time.

Bhojpuri songs are popular in Mithila-Madhesh due to linguistic similarities.

During the time of the release of the song, the trend of replacing mud houses with khapada (cylindrical interlocking clay tiles) roofing, with concrete houses had swept the region.

The decade-long Maoist insurgency from 1996 crippled the economy of the country; the political situation was unstable and unemployment at its peak. This was when Madhesh, and the rest of the country, saw a mass exodus of young men leaving for foreign shores for employment. The steady flow of men from villages to Gulf nations in search of employment was directly proportional to the number of new concrete houses mushrooming in the villages.

The trickle of remittance increased the income of almost every household. In Madhesh, those who went on foreign employment and earned money did two things—they replaced their tile-roofed mud houses with concrete houses and sent their children to private schools in cities.

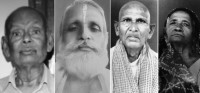

The increase in income courtesy of foreign employment and the association of tile-roofed houses with poverty attributed to the erasure of the built heritage that encompassed the architectural, cultural and social history of Madhesh, says Sahadev Pandit, a 70-year-old potter of Parwaha village in Kumhal Tole settlement in Aurahi Rural Municipality-2.

“It also meant that the craft of making and installing roof tiles got lost,” said Pandit. “It is a special skill but these days it’s a skill that doesn’t pay.”

Pandit spent his younger years baking roof tiles and clay utensils. “But now all my tools have been set aside, so has my skill. It no longer serves any purpose.”

Being a potter installing clay tiles roofing meant travelling far and wide. Pandit recalls the time when he would be living out of a suitcase for weeks and only visit his home once or twice a month.

“I started pottery when I was 10 years old. I used to travel, earn decent money, and meet new people. I have installed roofs in so many houses during my active years,” said Pandit. “But now my skills have no worth in this day and age.”

Most of the new houses in Madhesh are built partially or fully with concrete with either concrete or zinc roofing—a sign of modernisation that has worked several craftsmen out of their jobs, says Hridaya Kant Mandal, a 70-year-old potter of Parwaha village. “My skillset went out of fashion a long time ago, but who am I to complain? I myself have been living in a concrete house for more than a decade now.”

Phenhara village in Bishnu Rural Municipality of Sarlahi district near the Indian border was famous for its skilled pottery craft.

Sogarath Pandit, a 60-year-old potter of Phenhara, says the village has the dominant population of communities such as Yadav, Kumhal, Sah and Brahmin. Until two decades ago, most of the houses had tile roofing, but now only one or two houses carry the traditional feature.

One of the few structures with a tile roof is the Navaranga Hotel in Janakpur, the capital of Madhesh Province.

It is also one of the oldest hotels in the city, but it too is soon letting go of the heritage it has carried for so long. The hotel will now be housed in a concrete building from mid-April, informs Prakash Bhagat, the owner.

Bhagat, 35, says the maintenance cost of the tiles is costly these days and adds to the overhead burden of the business. “The repair and maintenance of clay roof tiles have to be done annually and the cost is high,” said Bhagat. “But the more pressing problem is finding skilled potters to make the tiles or replace them when needed. That’s why we plan to demolish the old structure and construct a concrete building.”

Navrang Hotel is just an example. Almost every house in Madhesh today is made of concrete. Mahabir Singh, a resident of Gaushala Municipality Ward 12, Mahottari, recently built a concrete house and converted his old mud house into a shed and store.

The difficulty in the maintenance of the clay tile roofing every year before the rainy season and the scarcity of skilled craftsmen to bake clay tiles prompted him to build a concrete house, he says.

“I decided to not demolish the old house because, during summer months, the mud house is much cooler,” said Singh. “I will live in the new house during the winter and the rainy season, but during the summers I will go back to my old house. I will try to maintain the old house, cost and skills permitting.”

Until 30 years ago, at the tail end of the rainy season and before the winter set in, potters would move around villages to make and repair tile roofs. The potters would move around in groups and spend months in one village making tiles because almost all the houses had tile roofing.

Clay tiles are traditionally formed by hand, then textured or coloured and fired in high-temperature kilns to set.

“Mudhouse with clay roof tiles, the walls covered in cow dung cakes, floors covered in a special mixture of water, cow dung, and mud was the identity of Madhesh. But the concrete houses have changed the face and identity of Tarai,” said Nitya Nanda Mandal, a writer from Janakpur.

According to Dr Revati Raman Lal of Janakpur, a cultural expert, special skills are required not only to make clay tiles but also to cover the roof. The installation of clay tile roofing is only possible in slope roof-style structures. Hay and yellow mud locally known as Piyari Mati is used as an adhesive to stick the tiles together and onto the frame of the roof.

The traditional mud houses with clay tile roofing not only hold cultural importance but also define the geography of Madhesh, says Lal. “The houses are made of simple materials such as mud, hay and wood which all are biodegradable and do not affect the environment like the way concrete structures do. There is no need to excavate rivers or dig mountains for stones. The materials needed in clay tile roofing last a lifetime and are reusable.”

Lal rues the vanishing of an important aspect of Madhesh with the disappearance of clay tile roofing. “Modernisation has had an adverse impact and has changed the intrinsic cultural values showcased through crafts by Madhesis. Mud houses did not need replacement in Tarai where the weather is mostly hot since mud houses and clay tiles act as coolants for the inhabitants.”

The nuclear family set-up; gentrification of rural villages and the declining practice of farming have also contributed to the disappearance of traditional houses in Madhesh, says Lal. “The disappearance of traditional houses has made way for the appearance of foreign folk culture, folklore, drama, patterns of worship and traditional games practised in Madhesh. Due to the changing structure of the house, the social connection between people and culture is also disappearing,” he said.

However, Engineer Mukesh Dubey of Mahottari disagrees and says that the physical structure of a house has nothing to do with the disappearance of culture and tradition.

“At a time when everyone is working very hard for a comfortable life, living in a mud house is a challenge. While the maintenance and upkeep is costly, finding a skilled potter, quality mud, and workers is a headache,” said Dubey. He argues that building a concrete house is a one-time investment and therefore a viable option for most people in Madhesh. “People don’t talk about the danger of snakes, leaking roofs and adverse weather conditions when talking about living in mud houses with clay tile roofing. Concrete houses are simply a safer option.”

Giving continuity to the craft is also a challenge in conserving the traditional housing system in Madhesh with the newer generation disinterested in taking up the craft.

Teji Pandit of Aurahi Municipality-2, a professional potter, died a couple of years ago. He left behind three sons, but none of them picked up the craft when their father was alive. The oldest son works at the Nepal Electricity Authority, the middle one runs a tea shop and the youngest is in Qatar for employment.

According to Jibchhi Pandit, a 70-year-old woman of Aurahi-2, the children of several renowned potters did not learn the traditional skill of pottery. The craft died with the older generation, she says.

“Now the children from traditional potter families also buy clay lamps for festivals because they don’t know how to make them,” said Jibchhi. “Everyone has chosen a different vocation from their fathers and forefathers. But you can’t really blame them, can you? The demand for clay tiles and clay products has decreased significantly, so a craftsman can’t survive on their skills anymore. Compared to the past, the earning from pottery work is very low.”

19.12°C Kathmandu

19.12°C Kathmandu