National

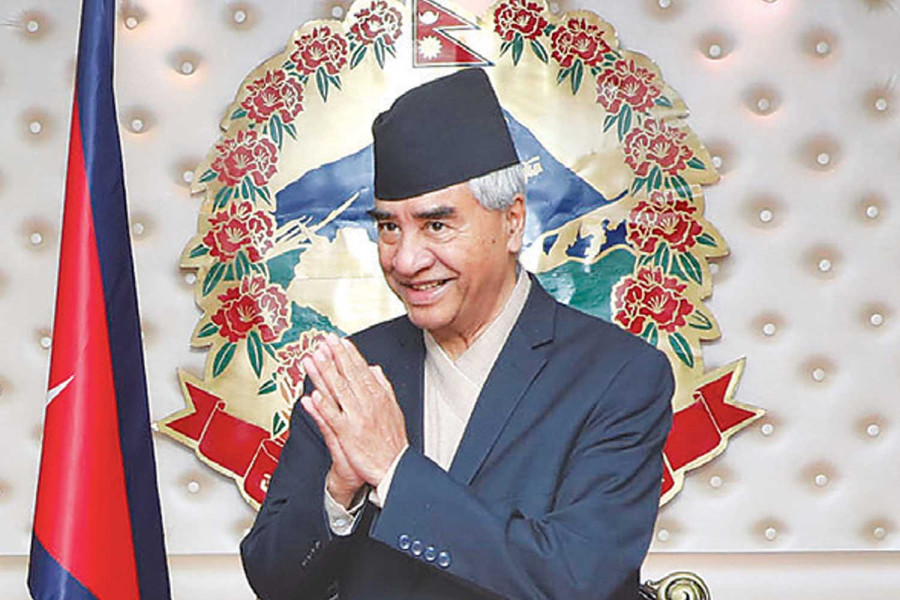

Is Deuba leading a caretaker Cabinet? Depends on who you ask

Ruling party leaders say the government is not caretaker; opposition says otherwise. Experts are equally divided.

Tika R Pradhan

After the announcement on August 4 of the federal and provincial polls for November 20, a debate is raging if the current Sher Bahadur Deuba government has become a caretaker or not.

The answer depends on who you ask.

Ruling parties call it a fully functioning government, but opposition leaders are terming it a caretaker one. Experts are equally divided.

To add to the confusion, parties, including the opposition, have agreed to keep the House of Representatives at least until September 17, as the Election Commission has worked on a schedule as per which the closed list of the candidates for proportional representation needs to be submitted by on September 18-19.

Some say the government will turn into a caretaker one when the election code of conduct comes into force while others say it will become caretaker only after the House term ends.

“This confusion has arisen because we are in a transitional phase as elections are happening after the full term of Parliament,” said Daman Nath Dhungana, a former Speaker. “But we all need to interpret things objectively, without being guided by partisan interests.”

But partisan interests are already in full display ever since the elections were announced.

Pradeep Gyawali, a lawmaker from the main opposition CPN-UML, said on Sunday while speaking in Parliament that the government cannot give business to the House as elections have been announced, implying that such a move could have long-term implications.

One basic principle a caretaker government usually follows in democracies is policy decisions should not be made once elections are announced as they can have long-term implications.

But Nepali Congress leaders say the government turns into a caretaker one only when the prime minister resigns, loses confidence in the House or the House is dissolved.

Min Bishwakarma, the whip of the Congress, told reporters that the government is not a caretaker one as the prime minister has not resigned, has not lost confidence of Parliament and has not dissolved Parliament.

Many, including Congress leaders, say the erstwhile KP Sharma Oli government had rather turned into a caretaker one after he dissolved the House—twice—and declared snap polls.

In the case when the prime minister dissolves the House, election dates have to be simultaneously declared.

Those arguing that the Deuba government is not a caretaker one say this time the elections that have been announced are periodic ones.

The UML, which refused to accept the Oli government had turned into a caretaker one after the House was dissolved, is now saying the Deuba government became a caretaker as soon as elections were announced.

Deputy leader of the UML Parliamentary Party Subas Chandra Nembang, who had told the Post after Oli dissolved the Parliament last year that unless the Election Commission issued the code of conduct the government could take necessary decisions, said on Sunday once the government declares polls, it automatically turns into a caretaker and cannot take crucial decisions.

The Deuba government, however, has continued to take a slew of decisions even after declaring polls.

While it prepares to push some old bills through the House and present new ones, it has transferred some police officials and intends to transfer more. On Monday, the Investment Board Nepal, whose meeting is chaired by the prime minister, took decisions on various hydropower projects. The ruling coalition is also considering bringing the Loktantrik Samajbadi Party in the government, and questions are also being raised whether a Cabinet reshuffle is possible after the declaration of polls.

Experts say since an election is about shoring up democracy and its outcome could send the current rulers to the opposition and vice versa, parties should rise above partisan interests and objectively decide about matters like the term of Parliament and when a government becomes caretaker.

“The parties in the government now could be sent to the other side of the aisle and the opposition party may lead the government after the elections, so all the parties should make an informed decision on such matters,” said Dhungana. “Politicians should speak objectively rather than thinking of serving their current and temporary interests.”

According to Dhungana, in principle, once the government declares the polls, it automatically turns into a caretaker, but the House has continued and this has created more confusion.

Dhungana, however, stressed that it would be better for the government not to take any decisions that could affect the upcoming polls.

“Maybe the government itself should clarify about its status,” said Dhungana.

Some of the decisions taken by the Oli government after the dissolution of the House and declaration of polls were annulled by the Supreme Court.

On June 22 last year, the top court quashed the Oli government’s decision to appoint a number of ministers, saying a caretaker government cannot induct new ministers.

The apex court had also annulled an ordinance brought by the government to amend the Citizenship Act. The decision was taken in response to petitions claiming that a caretaker government cannot take decisions that can have long-term implications.

Chandra Kanta Gyawali, a senior advocate who is also an expert on constitutional law, says the previous Oli led government had turned into caretaker because the House was dissolved.

But since this time the House, which is also an oversight mechanism, is still alive, the government has not turned into a caretaker.

And since it’s the Parliament where a government is born, some say as long as it remains functional, questions will also remain if the current government can be changed. What if the CPN (Maoist Centre), the key coalition partner with 49 seats, pulls out of the government, forcing Deuba to seek a vote of confidence. What will happen in the event of Deuba’s failure to win the vote of confidence?

Radheshyam Adhikari, a senior advocate and former member of the National Assembly, said the problem is a lack of proper conventions in Nepal’s parliamentary system.

According to Adhikari, developed countries and mature democracies function based on conventions rather than laws.

“We have a long ‘election period’... there is a gap of four months between the declaration of the date and the poll day. And it takes about a month to count the votes and install a new Parliament,” Adhikari told the Post.

Section 2(i) of the Election Commission Act 2017 states that "Election Period" means the time period between one hundred and twenty days prior to the election until the day when the election results are made public. But in cases where the date of the election has been declared in a manner in which the time period would be less than one hundred and twenty days, the time period between the date of such declaration and the day in which the final results are made public, shall be considered the election period.

“For how long can the state function with a caretaker government? It's a peculiar situation in our country. In other countries that have practised the parliamentary system for decades, elections are held within a month,” said Adhikari.

According to Adhikari, a government could be considered a caretaker after the closed list of candidates for proportional representation is filed.

“Until then, the government should function as usual, and it would be better if it does so in consultation with the main opposition,” Adhikari told the Post.

Experts say since the constitution has given the authority to conduct free and fair polls to the Election Commission, it can also tell the government when it turns into a caretaker.

“A democracy is also about good practices. Parties should also focus on parliamentary conventions,” said Bipin Adhikari, a professor and a former dean at Kathmandu University School of Law. “The Election Commission should tell the government that it should ensure an equal playing field for all to ensure free and fair polls.”

23.88°C Kathmandu

23.88°C Kathmandu