National

Will Kalapani residents fit into ‘my census, my participation’ motto?

Central Bureau of Statistics, the agency conducting the national census, is not sure whether it could count households and number of people in the region physically.

Prithvi Man Shrestha & Anil Giri

The national population census, which was halted due to the Covid-19 pandemic, is set to start from November. The Central Bureau of Statistics, the agency carrying out the gargantuan task, has made “my census, my participation” its motto. Questions, however, remain whether the people of the Kalapani area fit into this motto.

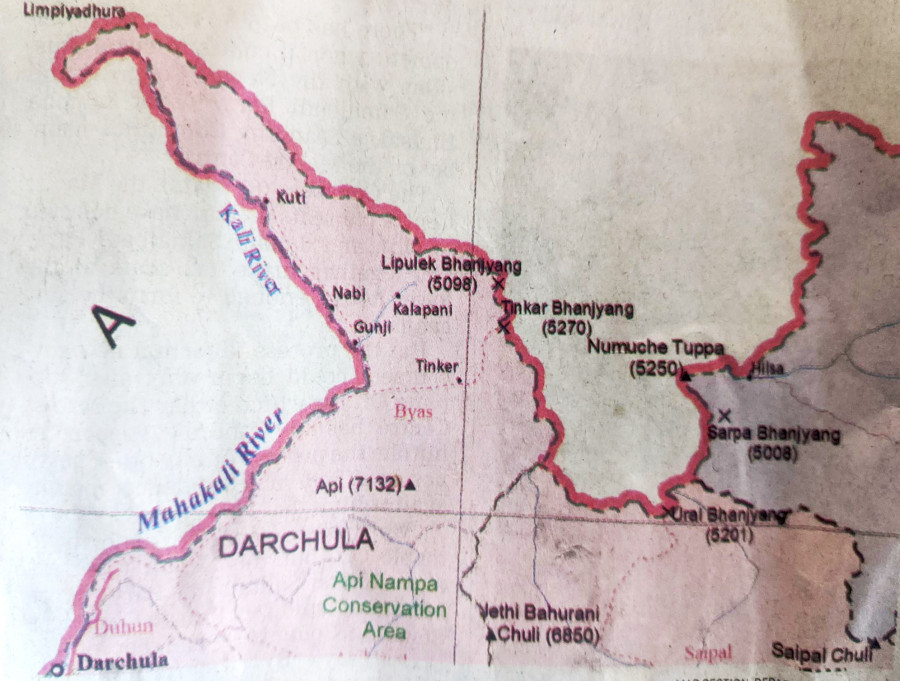

The census this year, 12th since it was started in 1911, is first since Nepal published a new map in May last year incorporating Kalapani, Limpiyadhura and Lipulekh within the Nepali territory, in an assertion that the regions belong to Nepal, not India, which claims them to be its own. This emerged last year as a major irritant in Nepal-India relations, with Delhi calling Kathamndu’s decision to publish the new map a cartographic assertion.

When the census was planned earlier for June, government officials had talked about some options to include the people in the region in the national head and household count. But no final decision has been taken yet.

“Our preparations [for census] are limited to the areas where we have our administrative control and where the local administration has promised security to our supervisors and enumerators,” Padam Pandey, district census officer in Darchula, told the Post over the phone. “We have already mobilised the supervisors to make a list of households before conducting the census.”

There are households in Gunji, Navi and Kuti areas beside the barracks of the Indian Army. There are no local inhabitants in Tilisi, which is currently Kalapani, and Nabhidang. There, however, are people in Chhangru, Tallo Kawa and Garbyang areas. Since these areas were not included during the 11th census conducted in 2011, there is no data on the number of households and people there.

Nebin Lal Shrestha, director general at the Central Bureau of Statistics, said that it is not that the bureau didn’t have any plan to conduct the census in the Kalapani region.

“It, however, is not easier to conduct a census in a region where it is even difficult to reach,” he said.

Nepali people still have to travel via India to reach the villages in the Kalapani region in Darchula. Jaya Singh Dhami went missing on July 30 when he fell into the Mahakali while trying to cross the river using tuin, an improvised cable crossing. He was on his way to Kathmandu, but for him to reach the district headquarters to catch a bus, he had no option than to cross Mahakali and get to the Indian side.

Shrestha said that one option to conduct the census in the Kalapani area is mobilisation of people “informally” as cross-border movement is not easy.

According to Shrestha, discussions are underway on ways to conduct the census in the Kalapani region at the National Planning Commission, the parent body of the bureau, and with the district census office in Darchula, but no decision has been taken yet.

“We are also planning to approach the Prime Minister’s Office and the Home Ministry regarding the matter,” he said.

In the case of failure to conduct a census by mobilising supervisors and enumerators physically, the bureau has also been discussing two other options.

One option is conducting an “indirect census”, which means counting the number of households using satellite imagery and estimating the number of people based on that. Another option under consideration is estimating the current population—based on India’s census report of 2011.

The bureau had floated these options earlier this year as well.

Hem Raj Regmi, deputy director general at the bureau, said these options are still alive if it is not possible to visit the Kalapani region for the census.

According to officials at the bureau, informal discussions have been taking place on these options at the planning body.

“Even to go for these options, a political decision is necessary,” said Shrestha.

Officials say such “indirect” methods have been used in the past too.

When the national population census was conducted in 2001, it could not be conducted with the physical presence of enumerators in several districts due to the Maoist insurgency.

According to the bureau, census work was affected in 957 wards (including 2 urban wards) of local governments (Village Development Committees and Municipalities) due to the Maoist insurgency.

Works in 83 Village Development Committees of 12 districts could not be carried out. Census was completely affected in as many as 747 wards of many local governments. Census was partially affected in at least two wards of two municipalities and some wards of 37 Village Development Committees.

In Salyan and Kalikot, even the listing process, which includes counting households and family members before the census through enumerators begins, was disturbed in some areas.

“In these districts, the population was estimated on the basis of a listing sheet and based on other estimation procedures,” the bureau said in its census report.

Shrestha said that they had confirmed the population of 23.1 million during the listing process, when the supervisors counted households and family members before the actual census. Details of 22.7 million could be accumulated during the actual census.

“So we could only provide characteristics (ethnicity, sex, profession, among others) of the 22.7 million population in our final report,” he said.

According to Shrestha, the bureau may not bring the characteristics of the households in the Kalapani region if the population is estimated based on the satellite imagery or India’s last census, like in the case of the 2001 census.

Officials say the bureau has already collected the data on the population in the region based on India’s 2011 census, according to which, there are 363 people in Kuti, 78 in Nabi and 335 in Gunji, the three villages in the region.

Buddhi Narayan Shrestha, a former director general of the Department of Survey, said that the government should conduct the survey in the Kalapani area. Otherwise there is no meaning of publishing the new Nepal map incorporating it within the Nepali territory.

During the general elections of 1959, people from two villages, Navi and Gunji, participated in the elections and voted overwhelmingly.

Later, the government conducted the census in 1961, and Nepali enumerators had reached the three villages.

Shrestha offered three different ways of conducting census in the Kalapani area.

“One is asking the people living in Chharung village of Nepal who have their relatives in those three villages—Gunji, Navi and Kuti. We can go to Chaharung and ask them whatever information they have,” said Shrestha. “The second way is to get satellite images of the households in these three villages and estimate the number of people in each household. But we will miss other details in this case.”

According to Shrestha, the third way is to analyse the data from the Indian survey of 2011 something the Central Bureau of Statistics too is considering.

“No matter whether we have a full or partial picture… full or partial census… we have to conduct the survey in the [Kalapani] region,” said Shrestha.

The Kalapani region, on the far west ridge of Nepal, has been disputed for decades, and has become a constant irritant in Nepal-India relations. The last time the issue emerged was in November 2019 when New Delhi published a new map to update its political map after detailing the boundaries of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh. The new map was unveiled after the Indian government on August 5 rescinded the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, paving the way for the creation of the Union Territories of Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh.

In the updated map, India showed the Kalapani area within the Indian territory, creating uproar in Nepal. Nepal’s attempts to hold diplomatic dialogue to resolve the issue went unanswered by India.

But in May last year, India announced that it was building a road link to Kailash Manasarovar in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, thereby forcing the Nepal government to make its own move of unveiling a new map, which was adopted by Parliament.

Experts say it’s incumbent upon the government to ensure that the census is conducted in the region so as to assert that the territory belongs to Nepal.

“Conducting the census is one of the best ways to assert that the territory belongs to us,” said Shrestha, the former director general at the Department of Survey who is known as an authority on border issues.

There, however, seems to be a lack of coordination among the state agencies regarding conducting the census in the region in question.

A senior official at the National Planning Commission said there has been no serious and in-depth discussion among the state agencies yet about conducting the census in the Kalapani region.

“We have to coordinate with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Home Affairs and security agencies, among others if we are indeed serious about conducting the census in the region,” said the official who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Phanindra Mani Pokharel, spokesperson for the Home Ministry, admitted that there has not been any discussion regarding the census in the region.

“Our primary duty is to make arrangements for security purposes,” Pokharel told the Post. “No line ministries have written to us as of now.”

Now that the census is set to start in November, concerns have grown, just as India continues to maintain its claim over the Kalapani area.

Officials at the Central Bureau of Statistics say they are ready to cover the area but they are worried if they can send enumerators as the move might cause further tensions.

“Indian authorities have prohibited Nepalis from going to the Kalapani area for the last several decades,” Dilip Budhathoki, chair of Byas Rural Municipality in which the Kalapani area falls, told the Post in April, two months before the census was to start earlier this year. “We are not sure if the census can take place in the region.”

9.41°C Kathmandu

9.41°C Kathmandu