National

Amid no progress, pandemic could become an excuse to delay justice to the conflict-era victims

There has not been a single investigation in the five years since transitional justice commissions were formed and its term is expiring again in nine months.

Binod Ghimire

Hardly had the new set of commissioners started their work at the two commissions set up to investigate the murders, tortures, rapes, disappearances and other cases of gross human rights violations during the 10 year civil conflict than the country went into a four-month lockdown and then in August came the prohibitory orders.

Appointed on January 18, the new teams at the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had just spent over a month learning the ropes of the commissions’ work and another month visiting their seven provincial offices.

“The Covid-19 pandemic hasn’t allowed the commission function as per its expectation,” Dipak Ghimire, an information officer at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, told the Post.

If the past performance of the five-year old commissions are anything to go by the pandemic is an opportune excuse for them not to perform.

Suman Adhikari, the former chairperson of the Conflict Victims Common Platform, one of many associations of the victims of the Maoist insurgency, said in informal meetings he has asked about the visions and strategies of the commissions.

“However, they don’t have any convincing plans to deliver justice. Even if there was no Covid-19 there would not have been any progress,” he told the Post. “It was clear from the very day of their appointment.”

The Comprehensive Peace Agreement signed between the government and Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) in November 2006 envisaged the formation of transitional justice mechanisms to look into and punish the perpetrators of the conflict-era atrocities including human rights violations.

But it took eight years for the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Act to be promulgated in 2014 and the two commissions were formed in February 2015 with a mandate of finishing their work in two years.

But soon after the parliament enacted the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Act, there was controversy.

In February 2015 the Supreme Court ordered the government to amend the Act. It said that the Act did not adhere to international principles of transitional justice.

The existing law gives the transitional justice commissions room for amnesty even in serious cases of human rights violations. The 2015 verdict says convicts in cases related to rape, extrajudicial killing, enforced disappearance and torture cannot be granted amnesty.

Different clauses of the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Act allow the transitional justice commissions to recommend amnesty even for heinous crimes.

For example, Clause 26 of the Act says if it is found reasonable to grant amnesty to any perpetrator [on the basis of the criteria set forth in other clauses] while conducting investigation pursuant to this Act, the Commission may make recommendation to the Government of Nepal.

The government has so far ignored the court order while the two toothless commissions formed on the basis of the Act have continued to collect complaints and have recorded statements of the complainants.

Since the Act was valid for only two years, it was amended in January 2017 to extend the terms of the commissions and the ten commissioners by another two years.

During the four years, the Surya Kiran Gurung-led Truth and Reconciliation Commission received 63,718 complaints and completed a preliminary investigation that involved recording statements from only 3,787 of the complainants.

Similarly between 2015 and 2019, the Lokendra Mallick-led Commission for the Investigation of Enforced Disappearance of Persons received 3,223 complaints from family members saying their loved ones had disappeared during the decade long conflict. Of these, the commission is investigating only 2,506 complaints from 66 districts saying other cases did not fall within its jurisdiction.

The Act was revised for a second time in February last year extending the tenure of the two commissions by two more years, but the tenure of the commissioners were not extended saying new commissioners would expedite the process.

New chief commissioners and commissioners were only appointed in January this year, nine months after the term of the previous commissioners ended in April last year.

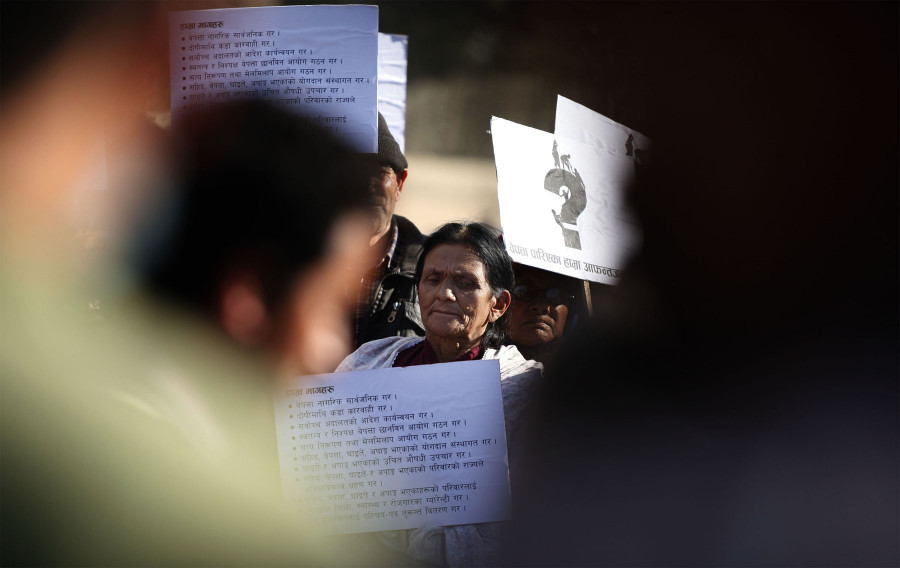

But victims’ groups and different human rights organisations opposed the appointment of the new chief commissioners and other commissioners in both commissions, saying they were picked based on their proximity to leaders of the ruling Nepal Commiunist Party rather than their expertise. They have been refusing to cooperate with those commissions.

Nepal Communist Party was formed in 2018 after the merger of the CPN (UML) and CPN (Maoist Centre), the main faction of the party that fought the ten-year insurgency.

“The parties didn’t bring them to conclude the transitional justice process but to prolong it,” Gopal Shah, chairperson of the Conflict Victims National Network, told the Post.

A member of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission agreed that appointment in the commission is based on political affiliation and is one of the reasons why they have not been able to work as expected.

“The actions of some of our members during our meetings show that they were appointed to sabotage the transitional justice process rather than to conclude it,” he said on condition of anonymity.

Even if the victims did cooperate, there is little hope that the commissions will be able to do much since their two-year tenure will expire in February 2021.

In the last seven months since its appointment in January, the team led by Ganesh Datta Bhatta at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is still verifying the 3,787 complaints the preceding team studied.

According to spokesman Ghimire, it has been going through all the complaints since January this year to see all of them fall under its jurisdiction. It has so far found around 2,000 cases that do not fall under its jurisdiction, since they are either from the time of the People’s Movement 2006 or from Madhes protests from different periods.

The commission plans to verify already studied cases and conduct detailed investigation, if necessary, or recommend for reparation and issue the identity card to the victims with which they will be able to get subsidies, Ghimire added.

“There could have been something at the commission’s hand by now to show its progress if it had got to work smoothly,” Ghimire claims.

Meanwhile, the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons since January has partially completed preliminary investigation of the complaints from one additional district of Rolpa, according Sunil Ranjan Singh a member of the commission.

“We will start inquiring about the perpetrators once the threat of the Covid-19 pandemic subsides,” said Singh.“The Covid-19 has definitely affected our output.”

However, there isn’t any certainty as to when the threat subsides.

But even if investigations were to be completed it is unclear what purpose it would serve since the government even six years after the Supreme Court order is yet to table a motion on the amendment of the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Act 2014 so that punishment for perpetrators are guaranteed.

A member of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission said the government has tied its hands by delaying an amendment to the Act as directed by the Supreme Court.

“The government had assured us of revising the existing Act as per Supreme Court’s verdict by the time we start our office but that never happened,” he said on the condition of anonymity. “Neither is there a proper law nor do we have necessary resources.”

The victims, meanwhile, are losing hope.

“Our hope that the transitional justice commissions would give justice has faded now,” said Bikash Gautam, whose father was forcibly disappeared by the state security forces from Sunsari district in 2002. “In last five years since their formation, the transitional justice commissions have only disappointed us”

Chiranjivi Gautam, a local leader of the then CPN-Maoist was arrested from Sunsari in May 2002. His family looked for him at the local police station and the Nepal Army barracks. But they denied they had arrested him.

Eighteen years have passed but the family does not know whether he is dead or alive.

“We want to know what exactly happened to my father,” said his son Bikash.

31.26°C Kathmandu

31.26°C Kathmandu