National

Despite quotas, gender stereotypes are still preventing men from becoming nurses

As gender stereotypes continue to see women as natural caregivers and nursing as distinctly feminine, men are often reluctant to pursue the profession.

Elisha Shrestha

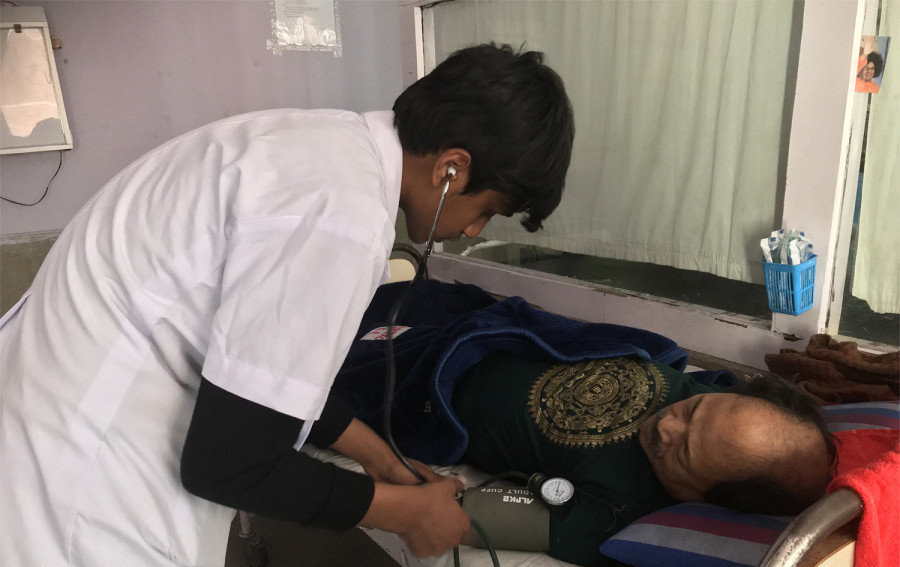

Clad in a white lab coat, Sagar Ranabhat stands attentively at Bir Hospital’s nurses’ station where the chief nurse is holding a team huddle before the start of the daily shift. In a room full of female nurses and students, Ranabhat is the only male present in the room.

Once the meeting is over, Ranabhat rushes towards the ward to which he is assigned with his sphygmomanometer, a device used to measure blood pressure, and a stethoscope to start his patient rounds.

Seventeen-year-old Ranabhat is a first-year student nurse, one of just a handful of males in the profession.

In his 40-member proficiency certificate level nursing class at the National Academy of Medical Sciences, there are just six men.

“I know that nursing is seen as a primarily feminine occupation,” said Ranabhat. “People are surprised when I tell them that I am studying to be a nurse, and I don’t blame them. Every hospital you go to and on every TV programme or film you see, nurses are always female.”

Unlike in other occupations, where women are usually in the minority, nursing is one of the few professions where women outnumber men greatly. Since nursing is perceived as an occupation that requires caring and nurturing qualities, women dominate the profession due to gender stereotypes that see them as natural caregivers.

According to data from the Nepal Nursing Council, out of 13,465 registered nurses, only 125 are male. This is largely because nursing continues to be associated with women and femininity, which has reflected in structural barriers to men pursuing the profession.

Before 1986, males were not permitted to study nursing, according to Goma Devi Niraula, president of the Nepal Nursing Council, the government body that oversees nursing in Nepal. In 1986, the government allocated 10 percent of seats for males in nursing programmes, but reinstated the restriction after just four years due to persistent stereotypes among both students and patients, said Niraula. But those four batches produced 80 male nurses.

Om Prakash Shrivastav was one of those nurses. As he had always wanted to work in the medical field, when the male quota was announced in 1986, he duly signed up.

“Nursing shouldn’t be stereotyped as a female profession,” said Shrivastav, who is one of three male nurses at the BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences. “Nursing is not only about providing care to patients; it is a highly specialised profession that requires nurses to work in a team where they are responsible for writing prescriptions, running surgeries and even conducting research.”

It was only in 2018 that the quota was instituted once again, one of the few professions where there is a reservation for men. The Nepal Nursing Council requires the country’s colleges to reserve 15 percent of available seats for men under the Council for Technical Education and Vocational Training (CTEVT) and Bachelor of Science in Nursing courses.

Although the council has made an attempt to address gender-based stereotypes, data from the CTEVT Examination Controller’s Office shows that a majority of colleges are struggling to fill their 15 percent male quota seats.

According to a CTEVT report on nursing enrollment, in 2018, at 110 nursing institutions that offer certificate-level nursing programmes, out of 4,067 students enrolled, only 58 were males. In 2019, there were only 59 males enrolled out of 4,049 students.

At the Alka Institute of Medical Sciences, there were just 2 male students who sat for the 2019 nursing programme entrance exams, said administrative officer Indira Baruwal.

“Neither of them enrolled in the programme and as a result, we gave the quota seats to female candidates instead,” said Baruwal.

At the National Academy of Medical Sciences, there are currently just eight male students enrolled in the nursing programme.

Although the quota system is a positive initiative to encourage males, Niraula believes that until society stops stereotyping nursing as exclusive for females, 15 percent male representation in nursing will remain a far cry.

Since Nepal’s constitution guarantees the fundamental right to employment, including no gender discrimination in regards to any job opportunities, decision to allow males to do nursing courses was made because preventing men from entering the field was against the law, said Niraula.

“The constitution guarantees 33 percent representation of women in areas where they are underrepresented. So the council started with 15 percent male representation in nursing,” said Niraula. “However, it seems like it will take time to change people's gendered perceptions of the profession.”

While the persistent socio-cultural perception of males as unsuitable to provide care can limit the presence of men in nursing programmes, Roshini Tuitui, director at the Nursing and Social Security Division under the Department of Health Services, believes that absence of male role models to look up to or offer advice about nursing can also influence the underrepresentation of men in nursing.

And Ranabhat agrees. Without adequate male nurses to look up to, he sometimes feels lost and even has doubts about career choice.

“It is too early to make any judgements regarding the profession, but sometimes, I wonder why there aren’t many male nurses and if I have made the right decision by choosing this profession,” said Ranabhat.

There is not a single male nurse at Bir Hospital.

But Tuitui is hopeful that the 15 percent quota will help rebrand nursing as a gender-neutral profession and encourage more men to take up nursing.

“It has been just two years since we allowed men to enrol in nursing so it will take time to break down stereotypes attached to this profession,” she said. “Nursing should be a diverse, inclusive, genderless profession. I passionately believe that by stereotyping nursing as a female occupation, we are not only preventing men from becoming nurses but are also promoting gendered expectations.”

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu (1).jpg)