National

A longing to return home, in safety and dignity

When the government of Bhutan expelled tens of thousands of its Nepali-speaking Lhotshampa population in 1991, branding them as “illegal settlers”, they fled to Nepal in hordes. Purna Bahadur Limbu was among those who crossed into Nepal via India with which Bhutan shared a poorly defined and largely unpatrolled border.

Dipesh Khatiwada & Arjun Rajbanshi

When the government of Bhutan expelled tens of thousands of its Nepali-speaking Lhotshampa population in 1991, branding them as “illegal settlers”, they fled to Nepal in hordes. Purna Bahadur Limbu was among those who crossed into Nepal via India with which Bhutan shared a poorly defined and largely unpatrolled border.

The expulsion was prompted by a census carried out in 1988, which identified around 113,000 Nepali-speaking people as “illegals”. It stoked tension between Nepal and Bhutan. Talks between then prime minister Girija Prasad Koirala and king Jigme Singye Wangchuck failed.

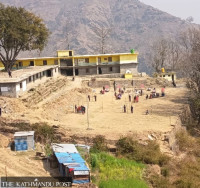

The migrants who then started living in seven crowded camps in two eastern districts of Nepal—Jhapa and Morang—got a new identity as refugees. They became “refugees from Bhutan”, or simply “Bhutanese refugees”.

Now, 87-year-old Limbu leads a tough life—he is asthmatic, blind in the left eye, and stoops due to old age. A hut in Beldangi, Jhapa has been his home for the last three decades but he is stateless.

Over the years, as part of the UNHCR’s resettlement programme, more than 100,000 refugees have resettled in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Denmark, Norway, Britain, the Netherlands, and Canada via Nepal but applications for the third-country settlement closed in December 2016.

Today, there are 6,500 registered refugees at two camps in Jhapa and Morang. Some 300 of them are elderlies who survive on aid provided by the World Food Programme. But June onwards, the UN agency will discontinue its support, for its “priority has now shifted from Nepal to other countries”.

“I really don’t know what will we eat after June?” Limbu told the Post on a lazy afternoon last month as he sat on a rickety bench in front of his hut numbered 108 Beldangi 3, sector “D”-2.

Limbu, whose health has been frail for some time now, cooks and cleans and does all the chores by himself. “There is no one to look after me,” he said.

His wife, Roharimaya, died when he was in Bhutan. When he fled to Nepal, he left his three daughters behind in Bhutan. His daughters were already married to Bhutanese men and were settled.

He then married Sukamaya in the camp in Jhapa, but she died 15 years ago. His third wife, Som Kumari, died two years ago.

For elders like Limbu, days are long and nights are longer.

“It’s tough to spend the whole day with nothing to do,” he said. “It’s hard to fall asleep at night; I think it’s because of my age.”

After free health services were also reduced in June last year, elderlies at the camps are bedridden with long-term diseases, and those who rely on daily medication for their health issues, have been left in a lurch.

Limbu, who needs regular medication for his asthma and joint pains, said, “In the past, we had free health services inside the camp. We did not have to seek medical treatment outside; I’m not sure how I’ll manage now.”

The Bhutanese refugee issue has been a tripartite matter since its start, involving Bhutan, India and Nepal, but India has for long recognised it as a bilateral problem between Nepal and Bhutan. Several pleas from the refugees to the Indian government to take initiatives for talks have fallen on deaf ears.

Ministerial-level talks between Nepal and Bhutan have also not been held since negotiations broke down after the 15th meeting in Thimphu in 2003.

In December last year, a Cabinet meeting decided to resume talks with Bhutan, but there has been no progress yet. With the third country settlement programme long over and the UN food agency halting its support, Nepal faces renewed diplomatic and internal challenges to seek a permanent solution to the refugee problem.

As per the UNHCR guidelines, there are three options for refugees: assimilation in Nepal, repatriation to Bhutan, or third-country resettlement.

Unfortunately, none of the options work for people like Limbu.

Nepal is not signatory to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol. Nor has it established a national legal framework concerning refugees and asylum seekers. As far as the third-country settlement is concerned, applications have been closed since 2016, and only those approved for family reunification can travel.

Three months ago, the UNHCR conducted a survey and collected data of the refugees who wanted to be repatriated to Bhutan. Only 944 families in Beldangi and 28 families in Pathari opted to return to Bhutan, among whom most are elderlies.

Repatriation of the Bhutanese refugees solely depends on the government of Bhutan. As Nepal has decided to resume talks with Bhutan to repatriate the remaining refugees, the issue will land in Thimphu only after Nepal’s Ambassador to India Nilamber Acharya, who is also accredited to Bhutan, presents his letter of credence to the Bhutanese king.

The Nepal government for now has agreed to provide primary health care and food supply to these two refugee camps.

“The Nepal government will provide food assistance and health services to the refugees after June 2019 and work on repatriation plans for them,” Ram Krishna Subedi, spokesperson for the Ministry of Home Affairs, told the Post.

Although the Nepal government has taken up the role of primary caregiver to Bhutanese refugees, a majority of senior citizens are worried about their future in Nepal.

Janga Bahadur Khadka, 80, who has been living in hut number-109 in Beldangi 3, “D”-2 with his wife Krishnamaya, 67, falls under the category “cannot make a living”; both have signed petitions for repatriation to Bhutan.

“I’m not in the best of my health; I’m in constant need of medical attention. But more than myself I’m worried about my wife, who suffers from mental illness. She developed this illness over the years and I don’t know how to take care of her,” said Khadka.

“There is nobody here to look after us; we don’t have children, we don’t have a family. Back in Bhutan, we have relatives who we hope will look after us.”

DB Subba, a leader of the repatriation campaign, said that most of the elderly hoped to return to Bhutan. “We have staged demonstrations for repatriation time and again but our pleas have fallen on deaf ears,” said Subba.

When the third country resettlement programme started in 2007, it gave hope to many of a better future, but some did not agree with the offer, saying it rather diminished all prospects of repatriation.

In May 2007, a group of Bhutanese refugees attempted what they called “long march to Bhutan” only to face resistance from Indian security forces. Nepal and Bhutan are separated by a strip of land which belongs to India. At least two persons died and 15 were injured in clashes with Indian police at the Miteri bridge which connects Nepal and India. No marches have been held since then.

Champa Singh Rai, a Bhutanese refugee rights activist who is also the secretary of the Sanischare Camp in Sanischare, Morang, said India has so far refused to acknowledge its role in the crisis.

“Since the Bhutanese refugees entered Nepal from the Indian soil, it becomes a tripartite problem. India looks at it as a bilateral problem between Nepal and Bhutan. All three governments must look into this matter seriously,” Rai told the Post.

With the issue of repatriation getting ensnared in bureaucratic and political quagmire, some refugees have also expressed their desire to assimilate in Nepal.

To this effect, they have submitted letters to the prime minister, home minister and minister of foreign affairs demanding local assimilation and recognition as Nepali citizens, given that they have spent more than 25 years in the country.

But the government has rejected local assimilation, saying Nepal hosted the refugees purely on the humanitarian ground as it is not a party to the UN refugee convention and protocol and that the country’s priority is its own people, not the refugees.

“I’m afraid we will be spending the rest of our life awaiting government decisions,” said Limbu. “Nothing in my life has been easy but this wait for things to change for the better is the hardest thing I’ve had to do.”

27.41°C Kathmandu

27.41°C Kathmandu