Money

Shrinkflation: You’re getting less for same price as packages become smaller

Firms are making product packets smaller instead of raising prices as high production costs bite.

Krishana Prasain & Pawan Pandey

Anishma Tuladhar of Bangemuda, Kathmandu is fond of momos, the most popular food in Nepal. Of late, she has noticed that the momos being served at her favourite momo joint have become smaller.

“I regularly eat buff momos at the Banglamukhi Mahabharat Momo Centre at Patan Dhoka. The owner has reduced the size from the last few weeks, but not raised the price,” said the bachelor-level student. “But it’s going to be costlier soon. The momo centre has informed us that the price will rise from next month to Rs140 per plate from the current Rs120.”

Banglamukhi momo is just one example.

Consumers are getting less of various fast food products for the same price.

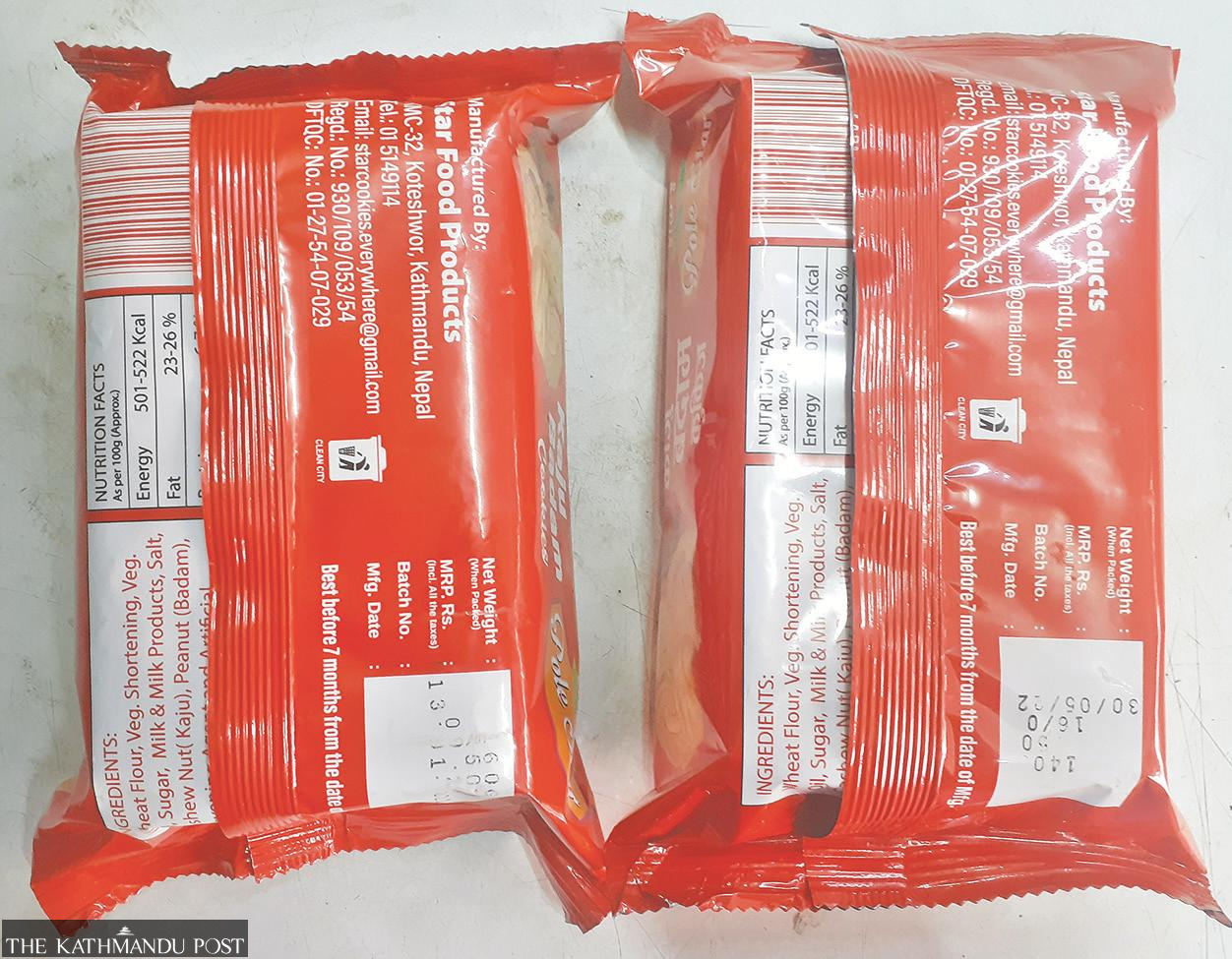

A packet of Kaju Badam Cookies manufactured by Star Food Products of Koteshwor has become thinner. Until a month ago, a packet of the cookies weighed 160 gm and cost Rs50. It still costs Rs50, but the weight has now decreased to 140 grams.

A 75 gm packet of Preeti noodles has become lighter by 15 gm but its price remains the same at Rs20.

A bar of Vim dish soap, imported from India, has shrunk from 155 gm to 135 gm.

A Wai Wai jumbo pack weighing 90 gm costs Rs25 as before, but the quantity has gone down by 5 gm.

Prices of leafy vegetables have shot up, and retailers are selling them by weight instead of by the bunch as before.

From makers of toilet paper to chips, and from toffee to juice, manufacturers are quietly making the packets lighter instead of jacking up prices.

The trend is accelerating worldwide, and it has been named "shrinkflation".

In economics, shrinkflation is known as downsizing the package to reduce quantity, which people hardly notice, without changing the price of the product.

Economists say this is a business strategy. If the price is hiked, customers will notice and complain, but they normally won't complain about the weight. This will keep the business running and customers flowing.

But consumer rights activists say it is cheating.

“As people are price conscious, reducing the quantity without increasing the price helps manufacturers to meet rising production costs,” said Ram Prasad Pudasaini, proprietor of Star Food Products. “The prices of raw materials have jumped several times.”

All goods, from food to cosmetics and from construction materials to beverages, have become costlier.

Compounding the damage left behind by the Covid-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has magnified the slowdown in the global economy, which is entering what could become a protracted period of feeble growth and galloping inflation, according to the World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects report released on June 7.

This raises the risk of stagflation, with potentially harmful consequences for middle- and low-income economies alike.

The report says that higher energy prices will lower real incomes, raise production costs, tighten financial conditions, and constrain macroeconomic policy, especially in energy-importing countries.

Policymakers, moreover, should refrain from distortionary policies such as price controls, subsidies and export bans, which could worsen the recent increase in commodity prices.

Nepal has imposed import restrictions to control the depletion of its foreign exchange reserve.

The federal government has adopted a policy of reducing imports by 20 percent in the next fiscal year in contradiction to its aim to boost revenue by nearly 22 percent from the projected collection in the current fiscal year.

This has raised questions about how the government will meet its revenue target by slashing imports which generate more than 50 percent of the country’s total revenue.

“Many products have seen their quantity being downsized,” said Deepak Adhikari, a shopkeeper in Koteshwor. “Customers hardly notice the drop in quantity, but it’s against consumer rights.”

Inflation is haunting everyone.

According to Nepal Rastra Bank, the year-on-year consumer price inflation jumped to a staggering 7.87 percent in May, hitting a 69-month high. It was 3.65 percent in May last year.

Prices of oil, both edible and non-edible, are already at record levels. In Nepal, apart from imported goods that come with inflationary prices, domestic products have also seen a hefty rise fuelled by spiralling petroleum prices, says Nepal’s central bank.

According to Nepal Oil Corporation, the price of petrol has reached Rs178 per litre, a 42 percent jump within the past year. The price of diesel has reached Rs165 per litre, increasing by 53 percent over a year.

Shrinkflation is now a global phenomenon.

In the United Kingdom, Nestle slimmed down its Nescafe Azera Americano coffee tins from 100 gm to 90 gm, say media reports.

In Japan, snack maker Calbee Inc announced 10 percent weight reductions—and 10 percent price increases—for many of its products in May, including veggie chips and crispy edamame. The company blamed a sharp rise in the cost of raw materials.

Domino's Pizza announced in January it was shrinking the size of its 10-piece chicken wings to eight pieces for the same $7.99 carryout price. Domino's cited the rising cost of chicken.

Nepali traders seem to have taken a cue from this global tendency.

“This is a result of the cost of production, which has increased by more than 30 percent in the manufacturing sector in recent months,” said Dinesh Shrestha, vice-president of the Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry.

Manufacturers say that the Russia-Ukraine war has disrupted the supply chain and made it difficult to get raw materials. “The price will obviously rise,” said Shrestha.

The Russia-Ukraine war has been projected to increase commodity prices by more than 20 percent, and this factor may impact Nepal’s growth and inflation, said the World Bank.

Chaudhary Group, manufacturer of Wai Wai, did not respond immediately to the Post.

Tikendra Siwakoti, country sales manager of Asian Biscuit and Confectionery, one of the largest fast-moving consumer goods companies in Nepal, said they had to reduce the weight of biscuits and noodles to remain afloat in the market due to the increased cost of production.

“We have reduced the weight of biscuits and noodles by 20 percent in recent months,” said Siwakoti. The company produces Digestive and Goodlife biscuits; 2pm, Rum Pum and Preeti noodles; Imli Bomb and Choco Luv and Goodlife and fruit juice.

Siwakoti said the company was maintaining the same quality and price despite reducing the quantity.

“We have reduced the weight of a packet of Preeti noodles by 15 gm. Even then, we are still incurring losses,” Siwakoti said.

While some manufacturers have increased prices and some have downsized the package, there are those who have done both.

“We have not reduced the quantity, but increased the price by Rs2 to Rs5 per unit from last month,” said Shiva Shrestha, head of marketing at Mayur Herbal which produces soaps.

“Besides the cost of raw materials, transportation charges have increased steeply in recent months.”

Kashi Kumar Das, national sales manager of Jasmine Hygiene Products which produces diapers, sanitary napkins and face masks, among other products, said they were planning to either reduce the quantity or increase the price from the next fiscal year beginning mid-July.

Economist Bishwambhar Pyakurel said that shrinkflation had become a global phenomenon due to supply chain constraints following the Russia-Ukraine war.

“It’s obvious that manufacturers globally are decreasing the size of the packets without increasing the price. Nepali manufacturing companies too are doing this," he said.

“The quantity in a packet of most imported packaged food and non-food items like dried fruits, toilet paper, yoghurt, coffee and corn chips has become smaller,” Pyakurel said.

But shrinkflation is nothing new, he said. “Manufacturers often adjust the packaging. This is an illegal approach but it will keep them alive in the market.”

Consumer rights activists say it is cheating in broad daylight.

“This is fraud. Downsizing the packets in the name of inflation is cheating,” said Bishnu Prasad Timilsina, general secretary of the Forum for Protection of Consumer Rights-Nepal.

“We are getting a flood of complaints from consumers about downsizing these days,” he said.

13.2°C Kathmandu

13.2°C Kathmandu