Money

Economy in crisis but how grave is it?

Economic turbulence looms large with half of the country’s income going to import bills. But situation manageable if immediate mitigation measures are taken, economists say.

Sangam Prasain & Krishana Prasain

The government's decision to form a committee to probe the actions of Nepal Rastra Bank Governor Maha Prasad Adhikari, which led to his automatic suspension, has ratcheted up the debate on Nepal’s economic crisis besides intensifying the political blame game. The Post has been consistently reporting over the months that Nepal’s economy is heading towards a crisis. In September, the Post wrote that the country’s foreign exchange reserves were coming under stress. Then in December, a follow-up story talked about how Finance Minister Janardan Sharma was oblivious to the impending crisis and was making unsubstantiated statements that the country would achieve 7 percent growth, which economists said was impossible. External vulnerability then continued to put pressure on foreign currency reserves, but the authorities concerned turned a blind eye to it. As oil prices rose, Nepal Oil Corporation started to pile up losses. Inflation concerns grew just as Sri Lanka faced its worst economic crisis since independence. Nepali politicians have started making superficial statements that Nepal is following the path of Sri Lanka. Is that true? How bad is Nepal’s economic scenario?

Here’s all you need to know about Nepal’s economic status.

What’s the size of Nepal’s economy?

Nepal’s gross domestic product (GDP), which is the value of all goods and services produced in the country, was Rs4.26 trillion in the last fiscal year 2020-21 ended mid-July 2021. GDP tracks the health of a country's economy. In other words, it is an indicator of how an economy is performing.

Why is a ballooning import bill a cause for concern?

When a country imports goods, it means an outflow of money.

Nepal’s annual import bill crossed the trillion-rupee mark for the first time in fiscal 2017-18. This was due to the reconstruction drive following the earthquakes of 2015 and a rise in disposable income as remittance earnings soared.

Three years later, Nepal spent a trillion rupees in just six months to buy foreign goods. This was because of growing demand for foreign goods as the country recovered from the devastating impact of Covid-19.

A high level of imports indicates robust domestic demand and a growing economy. But imports should be of productive goods like machinery and equipment because it will improve the economy's productivity over the long run.

But in Nepal’s case, government statistics show that a hike in the prices of goods is one of the key reasons behind the ballooning value of imports.

Reports say price gains are shooting higher across many advanced economies as consumer demand, shortages and other pandemic-related factors combine to fuel a burst of inflation.

“The situation is alarming,” economist Bishwambher Pyakuryal told the Post in a recent interview.

Some economists have termed the current situation a short-term phenomenon driven mainly by global factors. But if it continues, the consequences could be more serious, they say.

“If we spend one-fourth of our earnings on importing goods in just six months, it will increase business activities to some extent. But the reality is that it hampers economic growth in the long run because of low investment in critical infrastructure projects,” said Pyakuryal.

Eight months into the fiscal year, Nepal has already spent Rs1.30 trillion to import goods and services, while export earnings reached a meagre Rs147.74 billion, which is the country's best performance till date. The trade deficit remained at a staggering Rs1.16 trillion. These are worrying figures.

When exports do not perform well, a growth in imports will hit the country’s gross foreign exchange reserves, the source to pay for goods from overseas markets.

Nepal's gross foreign exchange reserves decreased by 16.2 percent to Rs1.17 trillion in mid-February 2022 from Rs1.39 trillion in mid-July 2021.

The country’s balance of payments remained at a deficit of Rs247.03 billion in the first seven months of the current fiscal year against a surplus of Rs97.36 billion in the same period of the previous year.

The current account recorded a deficit of Rs413.86 billion in the review period, up from a Rs104.39 billion deficit in the same period of the previous year.

How do imports affect the country’s foreign currency reserves and economic performance?

Foreign exchange reserves are a nation’s money saved for a rainy day.

The economic turmoil that Sri Lanka is witnessing today is due to a shortage of foreign currency or a balance of payments crisis.

In Sri Lanka, the outflow of money is more than the inflow, which, over the years, has led to the foreign currency crunch.

The island country relies heavily on imports. It imports petroleum, food, paper, sugar, lentils, medicines and transportation equipment, among other essential items.

But when Sri Lanka’s foreign currency reserves dried up, it led to a massive reduction in imports of essential items causing shortages on a wide level. Tourism, one of the key sources of foreign currency, too disappeared during the prolonged Covid-19 pandemic.

The extent to which Sri Lanka relies on imports is shown by the fact that the government even had to cancel examinations for millions of school students because it ran out of printing paper.

Sri Lanka is going through an economic meltdown of a scale unseen since its 1948 financial crisis, right after securing independence from Britain.

On March 22, the government ordered troops to prevent violence from breaking out at petrol stations as spontaneous protests erupted among motorists lined up for fuel.

Nepal too relies heavily on imports. It imports petroleum, food, sugar, lentils, medicines and transportation equipment, among other essential items.

If the country fails to maintain its foreign currency reserve, there could be a liquidity crisis which often leads to economic crisis.

“The country is already in a ‘first level’ crisis,” said economist Min Bahadur Shrestha. “If the government fails to manage things properly, the economic crisis could deepen.”

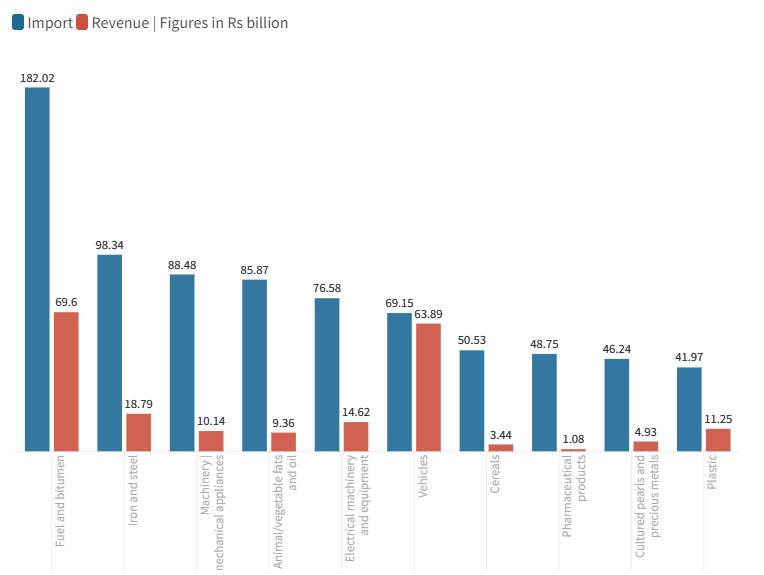

What are Nepal’s largest imports?

Nepal's largest import is petroleum products. As of the first eight months of the current fiscal year, imports of petroleum, iron and steel, and machinery and parts had crossed the Rs100 billion mark. Many other products may follow suit.

According to the Department of Customs, the petroleum import bill reached Rs184.98 billion in the first eight months of the current fiscal year, followed by iron and steel imports worth Rs127.75 billion and machinery and parts imports worth Rs100.37 billion.

Imports of transport vehicles and parts amounted to Rs75.95 billion in the first eight months; and Nepal, an agrarian country, imported cereals worth Rs56.93 billion, followed by crude soybean oil worth Rs43.74 billion, pharmaceutical products worth Rs52.22 billion, and electronic equipment worth Rs46.19 billion.

What are Nepal’s largest exports?

In contrast to imports, exports in the first six months totalled a mere Rs118.85 billion, resulting in a staggering trade deficit of Rs880.49 billion.

Nepal’s largest export is soybean oil, even though it produces very little soybean oil of its own, in fact, just 31,567 tonnes of raw soybean annually. This is not enough to meet the requirement of even a fraction of its own population.

But it exported 171,661 tonnes of processed soybean oil worth Rs41.40 billion in the first eight months of the current fiscal year.

Nepal exported processed soybean oil valued at Rs43.74 billion while importing crude soybean oil worth Rs41.40 billion, which means the value addition is just Rs2.34 billion. The second largest export is palm oil, of which Nepal does not produce a drop.

Nepal imported crude palm oil worth Rs30.82 billion while exporting processed palm oil worth Rs35.33 billion. The differences in export earning and import bill of the edible oil is the result of the tariff exemption on Nepali goods under the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) agreement that Nepali traders are enjoying.

Experts say there is no sense in being happy that Nepal’s exports have increased.

What measures has the government taken to curb imports?

The government has introduced a slew of measures to control ballooning imports.

Nepal Rastra Bank moved to discourage imports of 10 types of goods in a bid to conserve declining foreign exchange reserves as the first step. On December 20, the central bank made it mandatory for importers to keep 100 percent margin amount to open a letter of credit (LC) to import the listed goods.

As per Nepal Rastra Bank, traders need to keep 100 percent margin to open a letter of credit to import alcoholic drinks, tobacco, silver, furniture, sugar and foods that contain sweets, glucose, mineral water, energy drinks, cosmetics, shampoos, hair oils and colours, caps, footwear, umbrellas, and construction materials such as bricks, marble, tiles and ceramics, among others.

Motorcycle and scooter importers have to keep 50 percent margin amount, and importers of diesel-powered private automobiles also need to keep 50 percent margin amount compulsorily.

But there has been no indication of the import bill decreasing.

Last Monday, the central bank took drastic measures to control the outflow of money.

Nepali banks said they had received a “verbal directive” from the central bank to "discourage" traders from opening letters of credit (LC) to import non-essential goods in an effort to stem the outflow of the country's rapidly depleting foreign exchange reserves.

“Acting on Nepal Rastra Bank’s instructions, we have discouraged the opening of LC for non-essential goods,” Anil Kumar Upadhyay, president of the Nepal Bankers’ Association, told the Post recently.

“We have not restricted the opening of LC to import essential goods or production-oriented and agricultural products,” he said.

Automobiles, cosmetics, dried fruits, betel nuts, gold and silver are classified as luxury goods.

“The import restriction measures are a wise decision taken by the government,” said Shrestha, a former vice-chairman of the National Planning Commission, the country’s apex body that frames the country’s policy.

“It’s a first step to protect the ailing economy. And, so far, the move is good. Obviously, if we are energy surplus, the government has to reduce dependency on petroleum products and liquefied petroleum gas,” he said.

What are the government’s major sources of revenue?

The government is in a paradoxical situation: It has to control imports of products from which it earns the highest amount of tax revenue. Luxury items are the country’s major source of revenue. If revenue shrinks, an economic crisis could be imminent.

According to the Department of Customs, petroleum products contributed the highest amount of tax revenue amounting to Rs81.58 billion in the first eight months of the current fiscal year, followed by vehicles which accounted for Rs70 billion in tax revenue, iron and steel Rs21.38 billion, electric machinery and equipment Rs16.35 billion, plastic Rs12.77 billion and machinery and mechanical equipment Rs11.68 billion, and animal or vegetable fat which accounted for Rs10.35 billion in tax revenue.

Is Nepal really going the way of Sri Lanka?

Like Nepal, Sri Lanka is a country with a small economy. The Sri Lankan economy is around 1.5 times bigger than Nepal's. Sri Lanka’s economic crisis was in the making since it suffered a terrorist attack in 2019 which hit its tourism industry, a major contributor to the GDP. Then came the pandemic, which further wiped out tourism incomes. Then there were debt burdens in dollars.

The political leadership failed to act to address the looming crisis. The Rajapaksha dynasty that was governing the country made some wrong moves—it cut taxes and started printing money, hugely devaluing the currency. In what looked like a well-intentioned move towards organic farming, the county banned imports of chemical fertilisers. Paddy production failed. The country ran out of money to pay its bills.

In Nepal, the situation is not as bleak. Nepal’s current forex reserves are enough to pay for imports of goods and services for about seven and a half months, despite feeling pressure due to imports of petroleum products and some luxury items like automobiles. The central bank has been mulling over curbing imports of such items. Since remittance, a major contributor to the economy, has slowed, there is additional pressure. Tourism, one of the major foreign currency earners, was hit hard by the pandemic, but its gradual revival has given a glimmer of hope.

Since Nepal’s currency is pegged to the Indian rupee, a massive devaluation shock is unlikely. Tourism is also rebounding, giving a fillip to foreign currency reserves. Nepal received 42,006 foreign tourists in March, the highest monthly arrivals in almost two years.

22.92°C Kathmandu

22.92°C Kathmandu