National

Subject teachers shortage hits rural schools

Repeated advertisements for math, science, and English teachers have failed to attract candidates. Underqualified teachers have filled the gaps.

Santosh Mahatara, Manoj Paudel, Ram Prasad Chauhan, Tularam Pandey & Sudeep Kaini

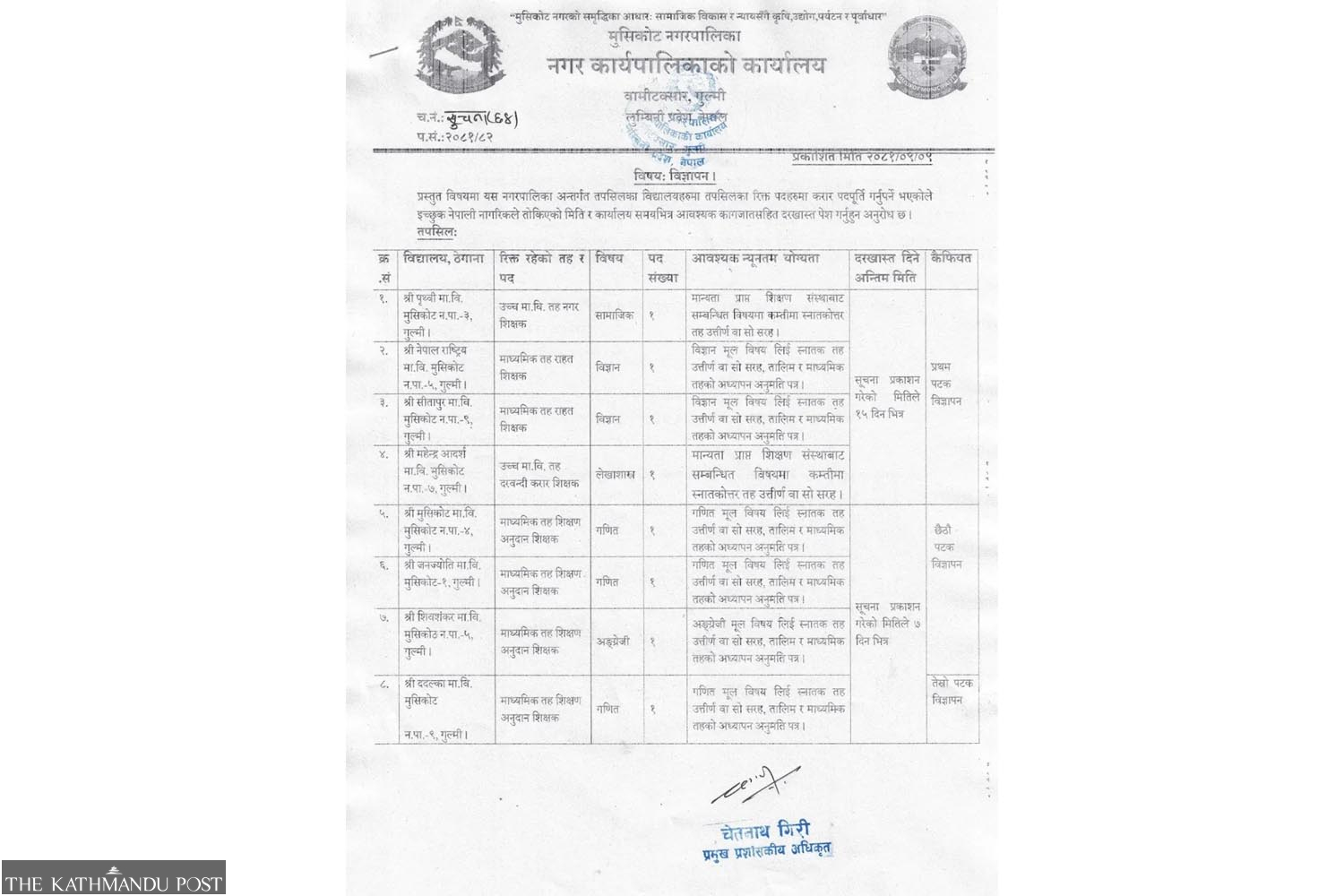

Musikot Municipality in Gulmi issued a vacancy announcement for a secondary-level mathematics teacher under the federal grant programme not once or twice but 15 times. Each call went unanswered. The education branch of the municipality has also been trying for a year and a half to hire English and science teachers, but the posts remain vacant hitherto.

“After repeatedly issuing advertisements without applicants, we stopped publishing notices altogether,” said Shyam Thapa, principal of the Musikot Secondary School in ward 4 of the municipality. “We are forced to run higher classes with lower secondary teachers, who already have no free periods. It has made teaching extremely difficult,” Thapa expressed his frustrations.

Shortage of subject teachers is widespread. Malika Rural Municipality’s Jamal Pokhara Secondary School announced vacancies for science teachers three times but did not receive a single application. “We now rely on lower secondary teachers to cover the higher grades,” said principal Dhundhi Raj Aryal.

Shukra Secondary School at Khadgakot of Kaligandaki Rural Municipality has a similar situation. “We advertised four times for a math teacher. No one applied. Since students began complaining, we’ve had to assign lower-level teachers to take secondary classes as well,” said Principal Prem Bahadur Pun.

Imparting quality education has been greatly affected due to lack of qualified subject teachers. “In Gulmi, a hill district of Lumbini province, finding mathematics, science, and English teachers has become nearly impossible. The lack of subject teachers has caused a visible decline in educational quality,” said Thaneshwar Ghimire, chief of the Education Development and Coordination Unit in Gulmi.

The picture is no better in Kapilvastu district. Aniruddha Public Secondary School in Yashodhara Rural Municipality has published four advertisements in the past eight months for lower secondary math and science teachers. “We could not appoint anyone,” said principal Ramesh Kumar Pandey. “The burden has shifted to existing teachers, and both students and teachers feel strained. We even agreed that teachers from other districts could transfer here if both schools consent, but senior teachers simply do not want to come.”

When Krishnanagar Municipality announced 51 volunteer teacher positions last year, no one applied for mathematics. Unsurprisingly, it is in these subjects—mathematics and science—that students perform the worst. Last year, out of 9,000 students who sat the Secondary Education Examination (SEE) in the district, 3,400 failed, with 2,400 failing in mathematics alone.

Education officials point to structural reasons. “Students who study math and science usually move into medical science, engineering, computer science, or forestry,” said education officer Arjun Kunwar. “Those who remain often migrate abroad. Among those who stay, very few want to pursue a teaching career. These are technical subjects, and the teaching profession simply doesn’t attract enough candidates,” he added.

In Bardiya too, repeated advertisements bring no relief. “For mathematics and English, we sometimes get applicants after a couple of calls,” said Dal Bahadur Chaudhary, senior education officer of Rajapur Municipality. “But for science, even after four advertisements, no one comes forward. Many who studied science don’t have the teaching license, and those who do are not interested in rural postings.”

The situation is further worse in remote districts like Kalikot, a hill district of Karnali province. Kalika Secondary School in Shubhakalika Rural Municipality advertised for a science teacher five times in the last academic year but found no eligible applicant. “The federal grant meant for science was returned unused,” said principal Saraswati Basnet. “We eventually hired an unlicensed teacher by collecting Rs25,000 monthly from parents. Even then, finding someone willing to work here was hard.”

Man Bahadur Shahi, chairman of ward 2 of Shubhakalika, admitted that even offering higher pay failed to bring in qualified staff. “We tried to bring licensed teachers by paying extra, but no one wanted to come. The federal grant for three subjects is going unused in many of our schools,” said Nawaraj Acharya, head of the education, youth and sports branch of Shubhakalika.

Principals complain that the licensing requirement is another barrier. According to them, even after completing a bachelor’s in science, one must either work for a year or complete a one-year B Ed to get a teaching license. Those with licenses prefer government service jobs or urban postings. Remote schools are left behind.

Veteran educators describe desperate measures. “I contacted networks across the country to find a science teacher,” said Man Bahadur Rokaya, principal of Dudhesillo Secondary School in Palata and Karnali chapter chair of the Nepal Teachers’ Union. “When no one came, I convinced a neighbouring school’s science teacher by offering an additional 10,000 rupees from our own funds. Even then, retention is uncertain.”

The shortage is not confined to rural districts. According to the Teachers Service Commission, out of 290 lower secondary science positions announced last year, only 281 could be recommended. While 3,873 people applied, just 1,213 passed the preliminary test and only 326 cleared the subject exam. At the secondary level, merely 11 percent passed the science teacher recruitment exam. For English and mathematics, the success rates were just 4 and 11 percent, respectively.

“The problem is twofold. First, there are too few posts in mathematics, science, and English compared to demand. Second, teachers do not want to go to remote areas. Even when we fill permanent posts, temporary or contract positions are left empty across the country,” explained the commission’s chairperson, Madhu Prasad Regmi.

Regmi also noted a deeper trend. “Those who pass often do not stay. As soon as they get the chance, they move to other government services. We cannot ensure long-term stability.”

A recent study by the Ministry of Education confirms that while there are more posts than needed at the primary level, both secondary and lower secondary schools face severe shortages.

As the shortage deepens, the quality gap between rural and urban schools continues to grow. For parents in districts like Gulmi and Kalikot, it is a daily anxiety. “We want our children to learn science and math properly,” said ward chairperson Shahi. “But without teachers, we are watching their future slip away.”

24.71°C Kathmandu

24.71°C Kathmandu