Miscellaneous

Wrecking ball

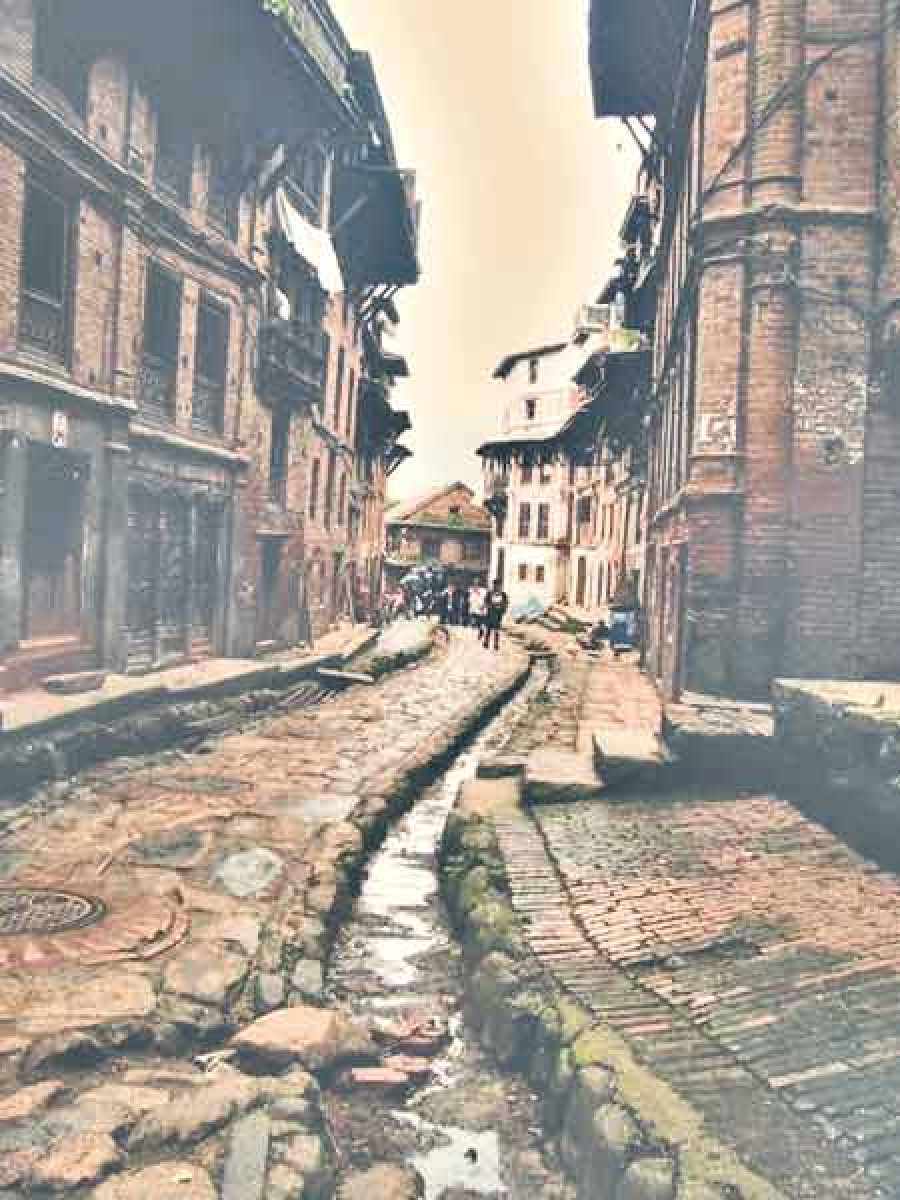

When the 2015 earthquake badly damaged our 100-year-old brick-mud-mortar home in Patan, we initially moved to knock it down and replace it with a concrete matchbox structure.

Barsha Chitrakar

When the 2015 earthquake badly damaged our 100-year-old brick-mud-mortar home in Patan, we initially moved to knock it down and replace it with a concrete matchbox structure. For a year, we pored over the drawings for the new house and building bye-laws—verifying the building’s height, number of floors and the types of windows we would use. Tedious as the process was, the family was looking forward to creating a new space that we could call home.

It was by a fortuitous accident that two conservation architects, who were privy to our modernisation plans, stumbled into our lives. Once the duo had inspected our home, they suggested that we renovate it, instead of knocking it down altogether. They pointed out that a retrofitted house would be just as strong as a new concrete structure,

It took a while, but the family slowly began to see the merits of a thoughtfully retrofitted building—both safety-wise and monetarily—and decided that we would preserve our house and all the memories it held, as it originally stood.

Later, I asked myself why we didn’t think of renovation earlier. Being an architect myself, I should have known better. I didn’t. In my two-and-a-half years of professional architectural practice, I wasn’t acquainted with traditional, old buildings and their age-old construction techniques, save for some minor details. I had read about how traditional construction methods make a building flexible during earthquakes—one characteristic that makes it earthquake-resistant. I had heard and read about it all. But when the April earthquake left our home with what looked like deadly cracks and bulges on the walls, the benefits of traditional construction technologies, which I had fondly studied for my undergraduate exams, slipped through those very cracks. And with the added duress of aftershocks jolting us every other day, we decided that our home wasn’t safe.

Renovation, a better option?

To be fair, we did make some post-earthquake assessments of our home with the help of civil engineers who, again, had very little knowledge of traditional buildings. Our assessment made it clear that; a) retrofitting could be done but would be too expensive, and b) renovation is only feasible for temples and palaces that have generous government and donor agency grants. It was not for residential houses; no matter that the commoner’s house was a little more than a stone’s throw away from the World Heritage Site of Patan Durbar Square.

But a detailed assessment by the conservation architects and our decision to renovate came as a blessing in disguise. Not only could we retain the spaces my grandfather had fondly built and preserve countless of memories created there by generations, we learnt that we could do this at half the cost of a new RCC (Reinforced Cement Concrete) house.

The renovation work has now been going on for seven months. And it has been an arduous task, to say the least. Dismantling a load-bearing structure in parts is no small task; add to that construction of new walls, some additions as per the modern day’s needs, old bricks coming down, new walls rising up, wooden joists being carefully lifted and removed.

While a handful of masons worked tirelessly, I couldn’t have been more grateful to the expertise of the head mason. His knowledge on traditional construction methods has been invaluable, more so to his willingness to lead this meticulous and, honestly, quite tedious construction work has been inspiring.

A happy medium

Because of the structure and complexities of renovating our row-house, like the many other in most old quarters of traditional settlements in the Valley, we incorporated some new technologies—steel structure for one. We added steel beams and columns in different sections. This has made the construction work a lot easier and faster. Although the strength of steel sections is tested, their compatibility with traditional construction methods has been questioned by conservation experts. Given that the entire renovation process has been somewhere in between traditional construction techniques and modern methods—with the use of RCC floor beams, wooden joists (Dhalin), wooden beams (Nina)—the use of steel structures might blend in well with the renovation methods we’ve been applying. Yet, we’re not sure. This hybrid method of renovation has been borne out of the existing conditions—structural complexities of a house in a row-housing settlement, the need to enhance structural strength, while economising on materials and money.

This latter part has been of even more concern to us given that the reconstruction installment tranches by the government is not currently being made available for renovation works. This means that if you decide to renovate your house, instead of tearing it down, then you’re on your own dime. And I can’t help but wonder what good this will bring to our traditional settlements where many houses, battered by the earthquake and weakened by the lack of maintenance over time, are awaiting uncertain fates. With no incentives to opt for renovation, aren’t you being forced to concreticise—reconstructing a taller RCC structure in place of your old load-bearing house? As a result, entire toles will be wiped of their traditional buildings, especially those that could have been renovated, saved and even made profitable.

This lack of incentives in reassessing damaged houses and renovating and salvaging what we still can, will only speed up the Kathmandu’s transformation into a concrete jungle. I’ve seen a beautiful neo-classical house in my tole having their well-proportioned pilasters and arches ripped off, for an RCC house with faux latticed windows to replace it. I worry that the nearby intricately decorated Sanjhyaa and another set of pilasters will have to bear the same fate if our current course is not corrected.

While we have renovated our home, in whatever terms and ways we could manage, I hope that other house owners too will follow suit. Understandably, housing is a primary concern. With proper incentives and guidance from the local authorities, the renovation process can gain new momentum—one that will retain much of the physical and social fabric that our ancient toles and bahas house. Because, as one heritage expert Bharat Sharma put it, “Bringing down the walls our ancestors built is easy. But saving heritage starts from preserving these walls, not from carelessly dismantling them.”

Chitrakar is an architect and an urban planner

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu