Miscellaneous

Hundreds of Flowers, One Nepali Garland

When members of the Nepal government decided to finally put forth a new constitution this year, it is highly unlikely that they had anticipated the ocean of Madhesi protests that have come to engulf Terai. One can imagine that the passing of the new constitution was supposed to be something exclusively symbolic—a ribbon of hope pinned to a year of devastation brought forth by the April and May earthquakes.

David Caprara

When members of the Nepal government decided to finally put forth a new constitution this year, it is highly unlikely that they had anticipated the ocean of Madhesi protests that have come to engulf Terai. One can imagine that the passing of the new constitution was supposed to be something exclusively symbolic—a ribbon of hope pinned to a year of devastation brought forth by the April and May earthquakes. What the government has prompted, however, is a movement of citizens demanding real change. In a wave of police killings and a blockade that practically shut down the entire country, Madhesis have made it clear that inaction is no longer an option.

Madhesis have occupied the center stager of this movement, but the calls for equal rights and representation in Nepalextend to all of the country’s marginalized groups. Demands for change have increased in intensity amongst women, Dalits, and other marginalized groups in the country, and a positive revolution is in the air if Nepal’s upper-caste politicians are willing to act like democratic leaders and listen to the people of their nation.

Of all countries in the world, the national anthem of Nepal has always struck me as one of the most beautiful. “Hundreds of flowers, we are one Nepali garland,” it begins. The anthem highlights the diversity of Nepal and acclaims its ability to live in harmony. The lyrics continue: “The diverse races, languages, faiths, and cultures are so extensive, our progressive nation, long live Nepal.”

Echoing this theme, the preamble of the new constitution promulgated in September states that the new Nepal government “end[s] discriminations relating to class, caste, region, language, religion and gender discrimination… in order to protect and promote unity in diversity, social and cultural solidarity, tolerance and harmonious attitudes,” and that it aims to “create an egalitarian society on the basis of the principles of proportional inclusion and participation, to ensure equitable economy, prosperity and social justice.”

Now, like the blacks fighting for civil rights in the USA who challenged the racist US government on its constitution claiming all citizens to be equal, Madhesisand other marginalized groups are demanding that Nepal live up to its own standards.

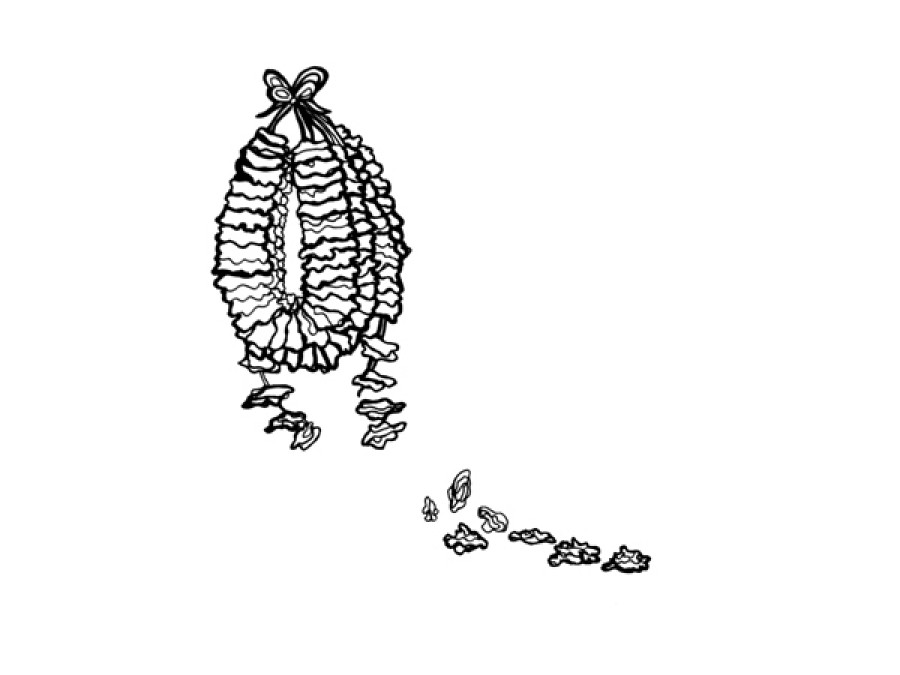

Broken Garland: Not all of Nepal’s ethnic groups are given a place within the national identity of Nepal.

Madhesis feel that they are not valued as citizens in the country beyond the material and historical resources found within the Terai. Though this region accounts for over 51% of Nepal’s population and produces over 45% of Nepal’s GDP, ethnic groups like Madhesis and Tharus often face lifelong discrimination for their dark-complexions and suffer from racist allegations that they are just Indians trying to influence Nepali politics and take over the country. Marginalized groups in the Terai often refer to their situation as an “internal colonization.”

“We Madhesis are called rough words like “dhoti” and “bhaiya” in school and in the workplace here in Kathmandu,” says Ram Pukar Mahara, a Madhesi student of Conflict Peace and Development studies at Kathmandu’s Tribhuvan University, who came to the capitol city for more opportunity. “The word “bhaiya” isn’t even a curse word; it means ‘brother,’ but people say it with so much hate that it comes to mean something like the racial slurs used against minorities in other countries.”

A wide variety of non-Nepali languages are spoken in the Terai, and people belonging to a caste or area in this region that speak Nepali rarely find themselves woven into any sort of “floral garland” of a tolerant Nepal.

“We are badly harassed, so when we have to stay together in a friendly environment and help each other,” says Lalu Ray Yadav, a migrant Madhesi construction worker that was making repairs on the UNESCO-listed Swayambhunath at the time of our interview. “Even the children here call us names and spit on us. The Pahari adults here have no problem with this.” When asked why he only makes 365Rs/day when the normal wage is 700Rs, Yadav responded matter-of-factly: “the minimum wage does not apply to us.”

One of the biggest points that are often used to bolster a sense nationalistic pride in Nepal is the assertion that the Gautama Buddha was Nepali. Historical artifacts do indeed indicate that the Buddha was born in the balmy Terai town of Lumbini, but with the current discrimination that Terai inhabitants are facing and the ubiquitous attitude in Kathmandu that Terai inhabitants are actually Indians and not “real Nepalis”, it makes one question whether or not the Buddha would be respected if he was born in his hometown today, and also just what sort of Buddha people are imagining when they assert that the Buddha was Nepali. Perhaps what they have in mind is a Buddha dressed in Daura-Suruwal, the traditional outfit of hill Nepalis.

-600x0.jpg)

Pahari Buddha: The sort of “Nepali Buddha” that it seems most Nepalis have in mind when they picture a “Nepali Buddha.”

Madhesi concerns may be legitimate, but the chosen means of making their voices heard through self-destructive bandas and blockade are not. It has been over 100 days that the region has been shut down due to bandas. The truth is that the banda is not so heavily-enforced in the Terai: shops are open, vehicles crowd the road, and people carry about their daily business. The ones who have suffered the most through this banda have been the children who have not been to school in over three months. The damage that is done to the future generation in these self-destructive protests is far more damaging to the side of the protesters than to their political targets in Kathmandu. If Madhesis are to move forward with their demands for civil rights, they should do so in a way that will empower their future generations—not force them into child labor and illiteracy.

Nepalis who make the claim that Madheshi demand slack a certain degree of solidity or an ending point are not without ground. There is no streamlined leadership or singular voice for Madhesi concerns; and internal squabbling, differing demands, and flairs in violence certainly do not make cooperation from Kathmandu easy.

But is it really a list of territorial and political demands that are what Madhesis are really after? Though there are obvious problems that need to be remedied, such as discriminatory citizenship policies, zoning issues, and unequal representation in government bureaucracy (which the new constitution of Nepal claims to address in its preamble), in one sense these are all red herrings. What Madhesis want more than anything else is to be accepted as a part of the country on a level deeper than paper documents, and this is a change that is going to have to come not from politicians, but from the hearts and minds of Nepali citizens.The desire to be accepted is one of the most fundamental desires of human beings, but currently Madhesis and other inhabitants of the Terai feel like they are outcast and unwanted in their own homeland.

If Nepal is to rise and fulfill its highest potential as a nation, the greatest task of the 21st century will have to be a remaking of national identity that stems from a realization that Nepal’s greatest strength is its diversity. Minority groups are not threats to national unity, but are its greatest seeds for success and flourishing. Nepal has been in a state of developmental paralysis for years, and this is largely because a small minority of privileged groups have taken power and stifled the bulk of the country in order to maintain the country’s age-old Brahminical power structure. In fostering a framework for developing the Terai and the other educationally and economically parched communities of the country, Nepal will break its spell of developmental droughtand witness a renaissance as a mosaic-nation of great strength and empowered diversity.

-600x0.jpg)

David on Twitter: @Caprarad

LM (the illustrator) at [email protected]

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu