Health

An incurable, difficult to diagnose illness with vague symptoms is afflicting many Nepalis

Lupus is an untreatable autoimmune disease that can affect nearly every part of the body.

Aakash Chaudhary

About three years ago, Benju Tandukar complained about constant fatigue, joint pain and swelling. She had skin lesions and rashes. Her family took her to various doctors. It took about six months to finally diagnose the disease.

Doctors said she was suffering from lupus, said her brother Mukesh. Benju was 10 years old then.

“By the time she was diagnosed, the disease had affected her kidneys and her condition had worsened,” said Mukesh, a resident of Patan, Lalitpur. “She was losing her hair. There were rashes all over her face. The last three years have been difficult for us, especially her.”

Lupus is an untreatable autoimmune disease that can affect nearly every part of the body such as internal organs, skin and joints. What makes it dangerous is it is chronic with no cure.

According to the data from Lupus Foundation of America, there are around five million lupus patients worldwide and nine out of ten patients are women. Most patients with lupus develop the disease between the age of 15 to 44 and three out of one suffer from multiple autoimmune diseases.

There, however, is no medical data on the exact number of lupus patients in Nepal.

Dr Sanjeev Acharya, MBBS, MD, a nephrologist at Sumeru Hospital, says since the treatment for lupus is an expensive undertaking, very few lupus patients seek a diagnosis and treatment.

“Most patients aren’t even aware of lupus. Lupus can affect any organ in your body. So far there is no cure for the disease even if one is willing to spend money for treatment,” said Acharya. “Without proper targeted tests, it is very hard to diagnose lupus.”

Very little study on the disease has resulted in a lack of awareness about this debilitating disease, according to Acharya.

There are four different types of lupus—systemic lupus which affects major organs in the body such as the heart, lungs, kidneys or brain; cutaneous lupus which affects the skin; drug-induced lupus and neonatal lupus in which the mother’s antibodies affect the foetus in the womb.

“Even in the field of medicine, especially in Nepal, there is a lack of research and awareness about how dangerous lupus is,” said Acharya.

Once diagnosed, the treatment of lupus by only one doctor is not possible. A patient has to see doctors from various fields to get systematic treatment which adds to the financial burden on patients and their families.

“Patients of lupus nephritis, which is categorised under systemic lupus, affects the kidneys. Patients have to visit optometrists, dermatologists, and nutritionists among others from time to time to keep the symptoms under control,” said Acharya.

According to officials at the Ministry of Health and Population, they have categorised lupus under incurable diseases in Nepal but do not have the data on the number of people affected by the disease.

Dr Samir Adhikari, joint spokesperson for the Health Ministry, says the government offers health insurance packages to those from impoverished backgrounds for the treatment of lupus as it does for patients with other long-term diseases.

“We do not have a tailor-made approach to tackle lupus as of now. The ministry has not conducted any awareness programmes or campaigns about lupus,” said Adhikari.

This lack of information about the disease leaves lupus patients and their families struggling to understand the disease.

Benju’s brother Mukesh says his family had a difficult time understanding what his sister was going through.

“She was sick, yes. But we didn’t know which disease. Her cognitive ability was also affected along with the functions of her organs. It took us a long time to understand that lupus was the culprit behind my sister’s erratic behaviour and outbursts,” said Mukesh.

Shristi Joshi, 36, was diagnosed with lupus in 2010. Her experience with lupus is not very different from Benju’s.

The disease left her picking up pieces in her personal and professional life, she says.

“Lupus affected my personal life and professional life very badly. It has been 12 years now and I am still fighting it. Days become hard to bear even when I am on medication. The symptoms come and go,” said Joshi. “I have already learned to live with lupus.”

To raise awareness about lupus, Joshi started an organisation dedicated to lupus patients. Lupus Nepal has more than 300 members and all lupus patients who can support each other. The organisation conducts awareness programmes and organises support groups for lupus patients.

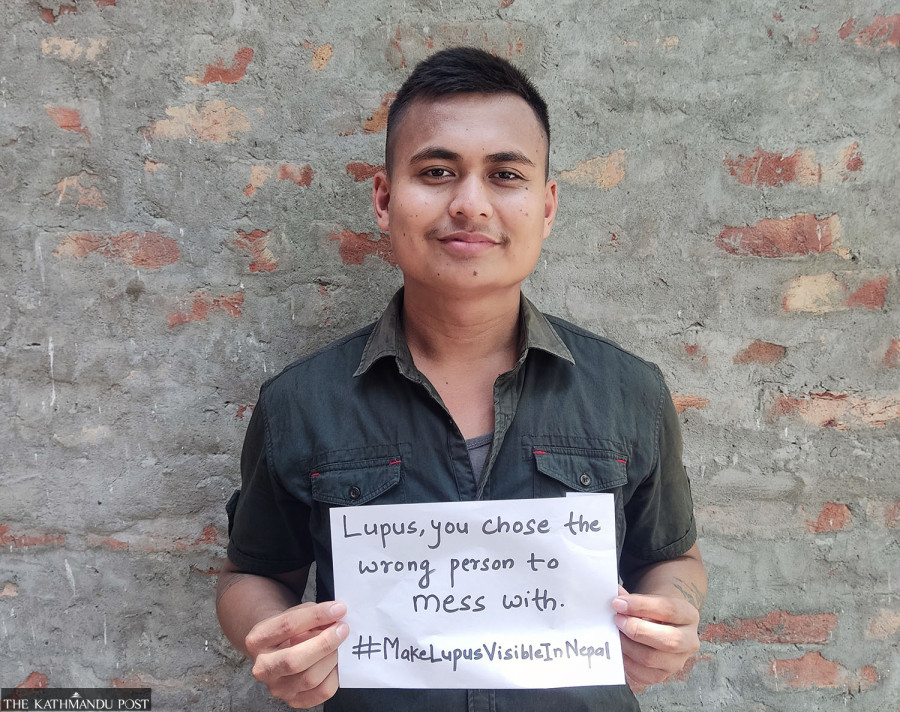

“The organisation has started a campaign called ‘Make Lupus Visible’ to inform people about the disease and its treatment. Lupus is still a lesser-known disease in Nepal which leads to delayed diagnosis,” said Joshi. “The delay in diagnosis only worsens the patient’s chance of seeking support and treatment.”

At a function organised by Lupus Nepal on May 6, Dr Buddi Poudel, a rheumatologist at Patan Hospital, said that there could be around 30,000 lupus patients in Nepal, diagnosed and undiagnosed.

Several studies have shown that people of colour are more likely to develop this disease.

“The cause of lupus is still unknown and the symptoms vary from person to person. Doctors will have to look at the symptoms, medical history and results from lab tests which include ANA (antinuclear antibody test) or AVISE CTD test—an advanced two-tier lupus assessment—and other tests which include anti-dsDNA or anti-Sm to confirm lupus,” said Poudel.

According to Poudel, lupus patients experience symptoms such as pain in the whole body, extreme fatigue, hair loss, cognitive issues and physical impairments. Several patients suffer from cardiovascular disease, stroke, disfiguring rashes, and painful joints. For others, there may be no visible symptoms or the symptoms just come and go.

“Although it is incurable, treating lupus patients with medicines that have been known to work and a healthy lifestyle can help lead a normal life. Regular checkups, good diet, exercise and medication can assuage the pain of lupus patients to some extent,” he said.

Bikash Chaudhary from Bara is 20. He was diagnosed with lupus at the age of 17 just when the Covid pandemic had begun.

When he first began showing symptoms, his family took him to various doctors. Like in Benju’s case, it took six months for diagnosis and a host of tests.

Bikash feared he would have to discontinue his studies.

“I was scared. I saw no hope. I was constantly ill that I couldn’t go back to college or even attend online classes,” he said.

But his family stood by him and provided the support he needed.

“With my family’s support, I have gradually learnt to live with lupus. I am still fighting. Living with lupus is hard physically, mentally, and emotionally,” said Bikash. “The sleepless nights, horrible pain, side effects from the medicine, emotional breakdown and fear of losing my life haunt me. But I am trying to get better.”

22.12°C Kathmandu

22.12°C Kathmandu