Columns

Digital gender gap

Pakistani women have it hard enough; digital technology should not set them back further.

Huma Yusuf

Pakistan’s human rights battles are now playing out across its digital landscape. The X ban drags on, fantasies of data localisation persist, and talk of further social media regulation is circulating. The state says it is indigenising internet infrastructure and better securing the nation. Digital and human rights activists are bracing for more censorship and targeted surveillance. In all scenarios, there is a risk that digital developments exacerbate gender inequality.

This is the key warning of a new report from Amnesty International on Gender and Human Rights in a Digital Age. The wider deployment of technology—whether for good or evil—brings with it risks of what Amnesty refers to as tech-facilitated gender-based violence. Both Pakistan’s authoritarians and activists should ensure that digital deployments do not exacerbate gender discrimination in our country.

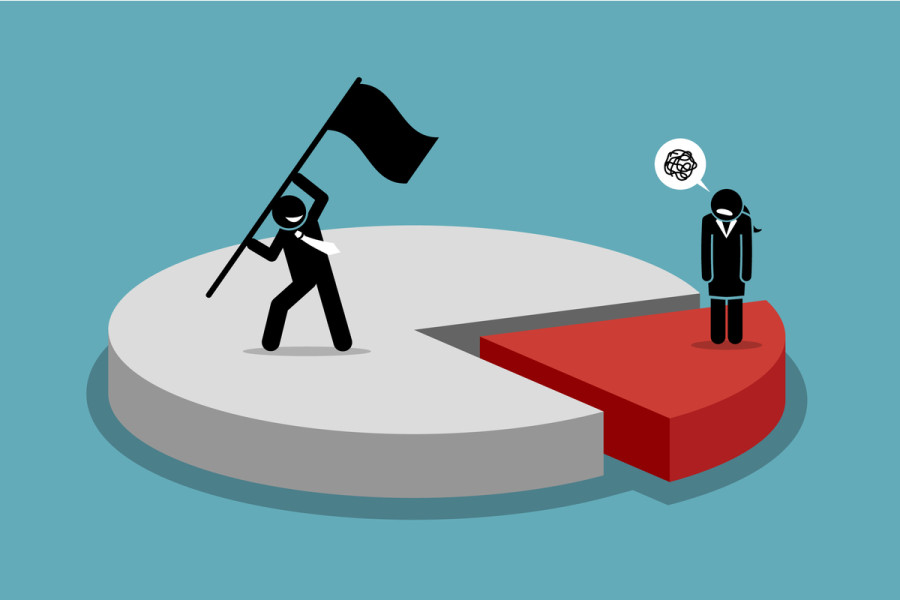

Talk of tech is by default optimistic, and marginalised groups have overall benefited from digital technology, whether through finding online communities of like-minded souls or accessing information and services previously denied to them. The greatest threat to this digital empowerment remains access: Pakistan’s digital gender gap is severe, with 26 percent of women accessing the internet as compared to 47pc of men.

While internet infrastructure is often posited as the solution to access gaps, the Amnesty report emphasises that the persistence of patriarchal structures in the digital realm means that discrimination endures even where infrastructure becomes available. One reason for this is the datafication of our lives. To exist in the 21st century, you need a data profile. And this profile is born from digital identity cards, online credit histories, e-bills to physical addresses, and yes, unfettered internet access. These are all things routinely denied to marginalised groups, particularly women, in the offline world. Any new digital regulation that prioritises security considerations over inclusion would be doing a disservice to the Pakistani people.

Data collection is also inherently discriminatory. The approach is often rooted in existing structural inequality, rendering marginalised groups invisible online as well. The Amnesty report points to digital identity systems as a key example of this. Think of our own national identity cards that require identification in the context of patriarchal family structures. Nadra is specifically called out in the report for deciding in 2023 to temporarily suspend the option for individuals to identify as ‘X’ in the gender category, leaving many transgender people without digital identification and so without access to other social services.

Of course, with more inclusive data profiles comes a greater need for data protection and privacy. For marginalised groups, datafication also means enhanced vulnerability. Such groups may go online to access information or services that are sensitive or stigmatised (for example, information about reproductive health). The ability to freely access and share information and services without fear of surveillance should be respected as a core human right.

There is also a gendered aspect to the economic opportunities that digitisation offers. The Pakistani debate on technology has become entirely securitised. But digital access is also about finding jobs in the gig economy, availing the benefits of digital entrepreneurship and ensuring that contract workers are fairly compensated by non-transparent algorithms. In all these arenas, women are at higher risk of reduced access to opportunity, discriminatory wages and oppressive workplace surveillance. Indeed, Amnesty argues that tech-facilitated gender discrimination is likely to worsen gendered poverty worldwide.

Once online, women are also more vulnerable to online harassment. In a 2022 HRCP report Rethinking the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, Farieha Aziz highlights how Peca has failed to protect women. Not only has the law failed to deter against online harassment, but it has also, she argues, exacerbated patriarchal oppression through its implementation. She documents how women who have sought justice under Peca have, instead, been subjected to additional offline harassment and intimidation by FIA officials, humiliation by lawyers, and retaliatory defamation charges. Such gender-based harassment should be the real security concern.

Sadly, women will also increasingly bear the brunt of state efforts to control the digital realm. This will be due to a vicious cycle in which women will turn to feminist activism or political protest to defend their rights, and then find those rights further trampled through digital surveillance and censorship. Pakistani women have it hard enough; digital technology should not set them back further.

-Dawn (Pakistan)/ANN

21.12°C Kathmandu

21.12°C Kathmandu