Columns

Literary responses to politics

Contemporary Nepali literature does not directly reflect the chaos in Nepali politics.

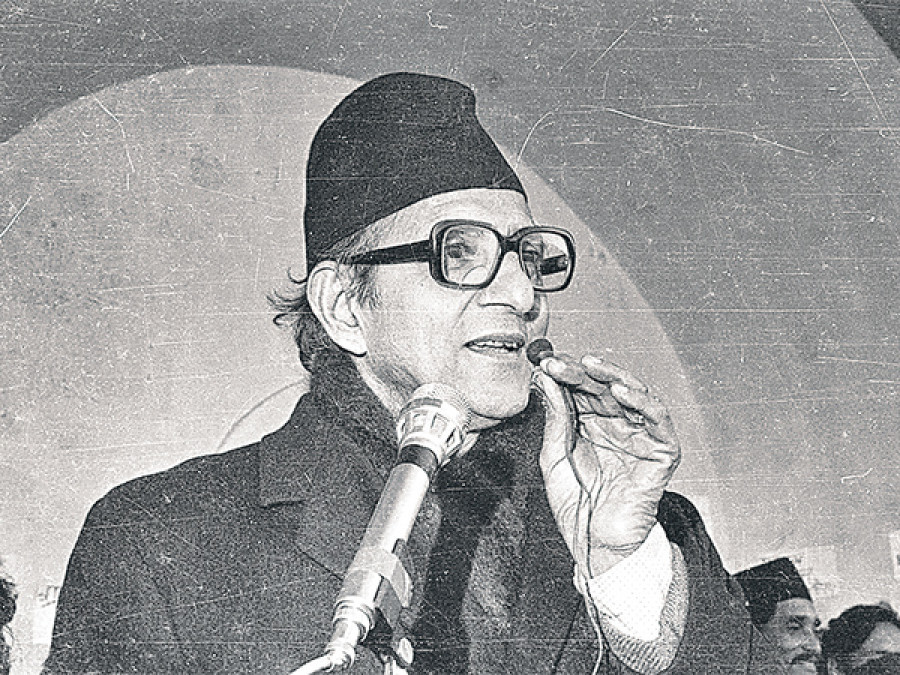

Abhi Subedi

I want to begin this short essay with a confession. The title would require a comprehensive discussion, which is not possible here. But I am trying to figure out the nature of literary writers’ responses to the political developments of this land. I see a certain pattern of order still working behind the brouhaha of Nepali politics and the unexpected changes happening today. After writing briefly about the diverse character of the order and failings, I will write about the tradition of literary responses to Nepali politics. One characteristic of Nepali literary writing today is that despite a plethora of publications of literary works of various genres, very few of them directly address the fluid political situation. There is a sense of dichotomy between literary writings and politics in Nepal. It is so strong that even the outstanding democratic leader and prominent literary writer Bishweshwar Prasad Koirala, alias BP Koirala (1914-1982), maintained a binary view of art and literature, to which I will return.

One prominent feature of Nepali democracy is the passionate response of people to its working. Though the response does not have a properly outlined shape, it is there, and it is working. One can make frank assessments about it. We can find some examples to show that it is functioning. Some of them are in order. People respond to all kinds of political developments in the country. They evince passion for freedom and democracy. And many people, especially the young generation, are remarkably proactive, which they show through the use of media and productive interventions in important issues such as holding political parties accountable for their actions. So far, everything is happening through law-abiding operations through political parties, and leaders sometimes create obstructions in that.

There is another side to the picture. The economic management is chaotic, as you can see and understand by watching pradesh samachar on television for half an hour every evening. That is a remarkable bit of audio-visual journalism. You can see the utter neglect of important projects, falling bridges, sliding roads, children studying in half-collapsed buildings, farmers’ fruits and vegetables rotting on their farms, and people affected at some time by rain and landslides living under dishevelled permanently temporary shades. They all commonly complain that the people who came to ask for votes for the local and national elections did not keep their promises. This side of Nepali conditionality is disheartening.

I turn to the question of literary response to Nepali politics, which has always made me pensive. As a Nepali writer, literary critic and an academic, I have always used this subject to problematise the response patterns to write about this subject and to interact with research scholars. Though drawing a neat conclusion about this subject is difficult, we can retrospectively make some observations. Like other literary writers and analysts, I, too, have made some attempts to do so, but they remain inadequate. I want to allude to a few past references before writing some paragraphs about the nature and subject of politics that would trigger literary writers’ responses. We get various examples of literary responses to the political conditions of the country but none so eloquently as the response of the prominent democratic socialist and literary writer BP Koirala whose confessions about his pursuit of literary writing and politics made in an interview given to a Nepali literary magazines are cited by both literary writers and people who make politics as the main vocation of their lives. In a famous interview given to a magazine called Arunodaya (15:1-2), Koirala says, and I translate: “In politics, I am inspired by an inner call, but in literature, it is just the opposite of that. I am a socialist in politics and an anarchist in literature. Art does not want security but freedom. Art does not want to step into the already-trodden path. It carves out its own course.”

It is interesting to see how the prominent politician felt it necessary to keep the two modes of perception and practice as two distinctly separate phenomena. Moreover, BP Koirala’s evocation of anarchism reminds me of a few other contexts. It seems that BP liked the Russian politician and literary thinker Leon Trotsky (1879-1940) at some point. I have not found references to say that BP was inspired by Trotsky’s concept of anarchism, which kept politics as a creatively important pursuit. It is a subject of research. As a prominent political leader and thinker, Trotsky had some interesting things to say about literature. In his famous book Literature and Revolution, he says: “The form of art is, to a certain and very large degree, independent, but the artist who creates this form, and the spectator who is enjoying it, are not empty machines, one for creating form and the other for appreciating it.”

This reminds us of what BP says about the independent nature of literature and its power to create its own path. Trotsky precisely puts it in these words: “It is not true that we regard only that art as new and revolutionary which speaks of the worker, and it is nonsense to say that we demand that the poets should describe inevitably a factory chimney or the uprising against capital!” BP has not fully explained his anarchist view of writing but has equated unimpeded experiments with its character.

I examined the literary response to the utopian vision of Panchayat polity by using BP’s writings and perceptions over two decades ago. I find it relevant to evoke my article “Literary Response to Panchayat Utopia”, published in the first issue of Martin Chautari’s journal Studies in Nepali History and Society (June 1996) in the present context of significant changes in Nepali politics and experiments in Nepali literature both in the creative and critical areas. I have analysed Koirala’s perceptions and writings by evoking the diverse “camps” of Nepali writers and the modernist writers’ method of ignoring the Panchayet polity. But I do not find it easy to tell what the common literary response to the current political transformations is like today. To respond to this question, I would like to repeat the binary between literary writings and politics, which I have attempted to deconstruct in a long article included in an anthology about BP’s writings published by the Nepal Academy.

I conclude with two impressions. The current Nepali literary writings do not directly reflect the chaotic character of Nepali politics. And the separation of literature and politics should not be pushed too far.

19.12°C Kathmandu

19.12°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)