Columns

Making federalism work

The federal budget must align with the Constitution and prioritise subnational levels.

Khim Lal Devkota

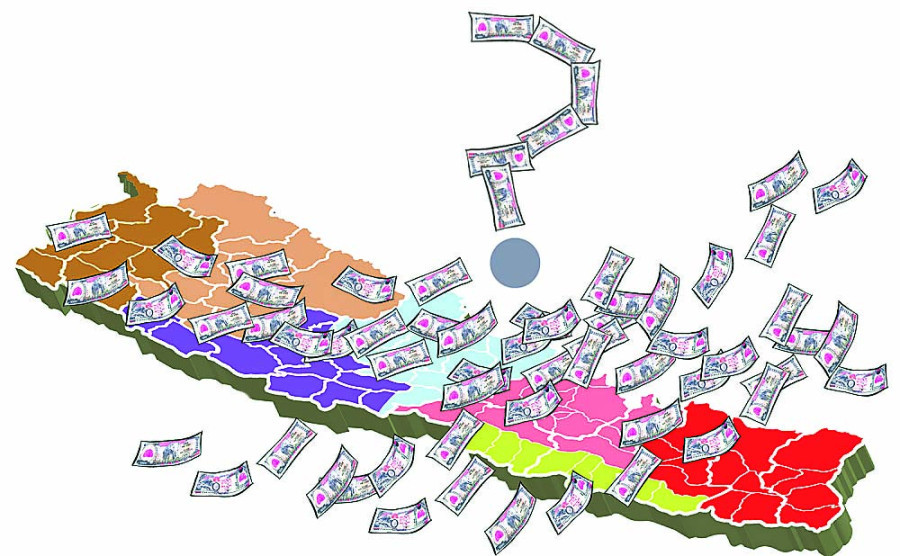

Nepal adopted federalism in 2015 to ensure power sharing among federal units, improve service delivery at the grassroots, and promote balanced, equitable development by ending Kathmandu-centric governance. However, seven years on, demographic and economic data reveal limited progress. Power and resources remain centralised, and meaningful transformation remains lacking.

In terms of economic distribution, provincial Gross Domestic Product (GDP) trends reveal the continued dominance of Bagmati Province. When federalism began in earnest with the first federal budget in FY 2018-19, GDP stood at Rs3.859 trillion, with Bagmati contributing Rs1.463 trillion—nearly 37 percent of the national GDP. By 2024-25, the GDP had risen to Rs6.107 trillion; yet, Bagmati’s share remained nearly unchanged at 36.5 percent, with a GDP of Rs2.230 trillion. This stability in proportional contribution underscores a persistent economic centralisation that federalism has failed to disrupt.

Provinces such as Koshi and Madhesh have maintained consistent shares in national GDP—hovering around 15.9 percent and 13.2 percent, respectively—without notable growth in their relative positions. Lumbini Province saw a marginal increase from 14.1 percent to 14.2 percent, while Gandaki remained around nine percent throughout the seven years (2018-19 to 2024-25). Most concerning are Karnali and Sudurpaschim provinces, which collectively represent a large geographical portion of the country but contribute only 4.2 percent and seven percent, respectively, to the national GDP. Despite having considerable natural resources and demographic potential, these provinces continue to lag far behind in economic development.

This stagnant economic structure highlights the limits of federalism in altering a historically skewed development model. Although functional, political and administrative responsibilities have been devolved to the subnational levels, economic activities and opportunities remain highly centralised. Bagmati Province continues to attract the majority of infrastructure projects, foreign and domestic investments, job creation and private sector activity. This trend is exacerbated by a lack of targeted policies to promote growth in lagging provinces, limited fiscal autonomy and weak institutional capacity at the subnational level.

The economic imbalance is not just a reflection of geography or population but a result of systemic preference. Investors, businesses, educational institutions and even government agencies continue to concentrate in or near Kathmandu, largely due to established networks, better infrastructure, and the perception of greater returns. While the Constitution lays the foundation for equitable distribution of state resources and opportunities, federal budgets over the years have not effectively prioritised provinces with greater fiscal needs. This has created a mismatch between the constitutional intent of federalism and its fiscal execution. None of the federal budgets presented so far is in line with the spirit of federalism. Although authority and responsibilities have been devolved to the subnational levels, the majority of the budget remains concentrated at the federal level, and its allocation is not justifiable.

Closely tied to the economic question is the demographic reality of federalism. The federal model also aimed to encourage population retention across provinces by improving service delivery, generating employment, and fostering local development. One key measure of federalism’s success, therefore, is whether people are staying in or returning to their home provinces rather than migrating toward the capital province in search of opportunities.

An analysis of the 2011 and 2021 population census data shows a continuation of past trends rather than a reversal. Bagmati, despite being the most urbanised and economically saturated, still experienced a rise in its population share—from 20.87 percent in 2011 to 20.97 percent in 2021. Likewise, Madhesh also increased its share from 20.40 percent to 20.97 percent, reflecting its growing role as an economic and demographic centre. Koshi and Lumbini maintained relatively stable shares of approximately 17 percent, while Gandaki saw a slight decline from 9.07 percent to 8.46 percent.

More alarmingly, Karnali and Sudurpaschim—two of the most remote and resource-constrained provinces—recorded stagnant or declining population shares. Karnali’s proportion of the national population fell from 5.93 percent in 2011 to 5.79 percent in 2021, while Sudurpaschim dropped from 9.63 percent to 9.24 percent. These declines suggest that emigration continues to be a major challenge, as residents leave in search of better employment, education, and healthcare—needs that federalism was supposed to meet closer to home.

When viewed through the ecological lens, the population is shifting from the hills and mountains to the more accessible and economically active Tarai region. In 2021, the Tarai region hosted 53.61 percent of the national population, up from 50.27 percent in 2011. Meanwhile, the Hill region's share declined from 43.01 percent to 40.31 percent, and the Mountain region from 6.73 percent to 6.08 percent. This shift further underscores the failure to develop the hill and mountain regions despite constitutional promises and legal mandates.

This outcome reflects a broader issue: Federalism has so far been more political and administrative than economic. While responsibilities have been transferred on paper, the corresponding resources—particularly capital investments, employment generation, infrastructure expansion, and private sector incentives—have not followed proportionately or strategically. Fiscal federalism, one of the most critical components for meaningful fiscal devolution, remains poor.

The gap between constitutional intent and policy implementation is stark in Karnali and Sudurpaschim. These provinces need targeted interventions for economic and demographic stability. As a lawmaker, I advocated recognising them—along with Madhesh—as special category provinces, with grants akin to India’s support for its underdeveloped states. Without major investments in infrastructure, energy, education, health, and connectivity, these provinces will keep lagging, perpetuating the inequalities that federalism aimed to reduce. Additionally, without private-sector incentives beyond Kathmandu, economic centralisation will persist, undermining federalism’s foundations.

The way forward requires not only stronger fiscal transfers based on need and performance but also a strategic vision for provincial development. Provincial economic hubs must be developed with sector-specific priorities—such as tourism in Gandaki and Sudurpashchim, agriculture in Madhesh, energy in Karnali, and industry in Lumbini. Provinces must be empowered with adequate legal and institutional tools to plan, execute, and manage development independently and effectively. The federal government, for its part, must demonstrate the political will to redistribute not just authority but opportunity.

To truly make federalism work, the federal budget must align with the Constitution and prioritise subnational levels. Yet in the 2025-26 Budget Speech Booklet (Schedule 4), only nine percent of the total budget is allocated to provincial and local governments—a figure that must be substantially increased. According to the 2024-25 Economic Survey, there is a significant staffing shortfall at subnational levels, while the federal level has surplus personnel and bloated institutional structures. This imbalance must be urgently corrected.

Making federalism work also requires balancing fiscal autonomy through fair revenue sharing and equipping provinces and local governments with adequate financial and human resources. Strengthening intergovernmental coordination is vital to prevent duplication, ensure good governance, and achieve sustainable development. Budgets must reflect local needs—not just central priorities—ensuring grassroots voices shape national development.

Key laws on civil service, education and policing must be enacted, and political party structures should adapt to the federal model. Without these reforms, federalism will remain incomplete. Implementing the National Assembly’s Special Committee report is essential for achieving the constitutional vision of inclusive, equitable, and effective federal governance.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu