Brunch with the Post

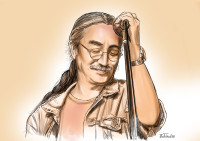

Lex Limbu: Love should happen to everybody

The UK-based blogger speaks about the progression of LGBTIQ rights and awareness in Nepal, his ongoing advocacy work, and his connection with Nepal.

Pranaya SJB Rana

Lex Limbu has just arrived from the premiere of Xira, a film starring his close friend Namrata Shrestha. The film is unique, he says, as Shrestha plays an MMA fighter. He's generous with his praise, but he touches upon one aspect of the film that he's found interesting.

"It breaks stereotypes in a subtle way, like when the female character comes home, her husband is the one making dinner," he says, perusing the menu at the new Chimes restaurant in Sanepa. "It’s nice, but it’s so sad that we have to be happy with that."

That gradual progression in sensibilities, not just in popular culture but also in broader society, is what Limbu himself has been fighting for. The changes he wants might seem big, but they're really not. In any modern, progressive, rights-based society, they would be given. But in Nepal, things are more complicated.

Limbu, largely popular as a blogger, came out as gay two years ago in a video that was celebrated for its bravery, poignancy and emotional honesty. Since then, he has gone on to become a defacto spokesperson for queer rights, doing interviews, launching awareness programmes, and attempting to educate a largely conservative Nepali society. He did a ‘HIM & I’ photoshoot showing two men in love and he’s launched a series of Pride Nepal t-shirts—all to increase visibility in Nepal.

"Visibility starts conversations but those conversations need to include everyone, including those people who say ‘don’t make such a big deal out of it’,'' he says, before deciding to “go basic” and order chicken momos to go with his glass of chardonnay.

Limbu believes in difference, that everyone's lives and journeys are different from one another's. Even within the LGBTIQ community, the difference is vast. There is identity, but there is also class and caste and geography.

It is this diversity of the queer experience that Limbu wants to unpack. All too often, straight Nepalis tend to lump the entire spectrum of genders and sexual orientations into one category—tesro lingi, or third gender. Even gay men and lesbian women are often referred to as third gender.

That was bound to happen, says Limbu, as the organisation at the forefront of the gay rights movement in Nepal has been Blue Diamond Society, which has a lot of transwomen members.

"The LGBTIQ community is so diverse," he says. "But this perception will not change until more gay men and lesbian women start coming out."

Limbu isn't about pressuring anyone to come out. Everyone has their own journey and their time and place, but if a few influential people came out, perhaps that could be a catalyst, he says.

"When people ask me for advice on coming out, I tell them not to rush. It took me 25 years and I had my own conditions like I should have a job and should have finished my studies. But there shouldn’t be conditions," he says. "You know your family, you know the people around you the best, if you think they get it and that you’ll be able to educate them, come out. But there’s no rush."

Visibility is one thing but awareness and education is another. There's still a lot of misinformation and misconception about the LGBTIQ community. It shouldn't have to fall to queer people to educate others but that's a responsibility that Limbu has taken upon himself.

"Sometimes, in Nepali articles, they use a feminine verb to refer to me," he says. "So a lot of what I’m doing is breaking things down. I tell people that I am a male who likes another male. I want to stay male; I don’t want to become a woman. I guess it's the burden of being born at this time, that you have to spread knowledge."

Limbu understands the frustration with having to explain something as natural as your orientation to others but he also understands why there might be a difficulty. Each time he comes to Nepal from the UK, where he lives, he makes a point of going on the radio or speaking to the press, especially in the Nepali language.

He’s encountered difficulties, as have many others in the LGBTIQ community, with the media but he takes it in stride.

"I don’t get angry. I explain things to them," he says. "People might say the wrong thing, they might misgender me, but we can’t make enemies of everyone right now, or they’ll never write about us again."

The Nepali media remains largely conservative and it often stumbles when it comes to identity and gender. Many queer people don't take kindly to these kinds of mistakes, often leading to a vocal backlash on social media.

"I see a lot of anger online but we’re all in this together and unless we explain things clearly, nothing is going to change. We can’t teach them everything all at the same time," says Limbu. "We have to start with the basics. What is love? What is discrimination? Do you know anyone who is LGBTIQ?”

Nepal's LGBTIQ movement has come a long way, with a lot of gains over the years. The constitution explicitly recognises the community and ensures full rights; there are provisions for third gender on official documents; and a 2007 Supreme Court ruling had even asked that same-sex marriage be legalised. Although there is little progress on that last front, legally, things are better here than in the rest of South Asia. But all too often, these provisions haven’t translated into action.

“I don’t think the politicians believe in what they wrote in the constitution,” says Limbu. “It’s just work for them. But we also have to understand that everyone’s doing their best to get by. They were probably thinking, let’s just tick this box. Fine, but let me educate you now, let me make you an ally.”

Limbu claims to have the ability to turn anyone into an ally and after sitting with him for an hour or so, I believe it. He is open and level-headed, approaching every issue with earnestness and positivity. But not everyone has his patience. Even within the LGBTIQ community, schisms are growing. Although Nepal has held an annual pride parade, led by the Blue Diamond Society, on Gai Jatra for over a decade, this year, a separate pride parade was held in June, organised by Queer Youth Group and Queer Rights Collective.

“That’s because they come from two different schools of thought,” says Limbu. “I really appreciate the Nepal Pride Parade that took place in June. It was a very impressive thing. That young group is very aware and switched on with what is happening in the west. But I’m not sure how relevant their knowledge is when it comes to things happening outside of Kathmandu.”

Limbu doesn’t see this as a competition. Both groups can hold events throughout the year, that would actually be better, he says. But he wants to stress that in the end, they should work together to promote queer issues, not dilute them with divisions.

As someone who lives outside of Nepal, it was difficult for Limbu himself to understand the lives and experiences of queer people from across Nepal, especially those from outside Kathmandu. This was part of a larger issue for him, namely his disconnection with the country itself. That was what prompted him to start Tracing Nepal in 2014. As part of the programme, Limbu brings together Non-Resident Nepalis who’ve grown up outside the country and takes them on a trip to Nepal.

“We do social activities so it’s kind of like voluntourism but done the right way,” he says. “I tell them that what you’re doing for a few weeks will not change anything but it will change something in you.”

This experience, too, is part of owning your identity. For the increasing number of ethnic Nepalis who are growing up outside of Nepal, Tracing Nepal gives them a chance to decide whether they feel like they have a connection here.

“If you’re outside and you feel like going back, do it. If it works for you then that’s great but if not, its okay to live abroad,” says Limbu. “At least you’ll be much more okay with how you identify yourself and where in the world you belong. Or maybe you’ll realise you don’t belong in either place.”

Nepal is changing fast, and many who live abroad don’t seem to understand that, says Limbu. The older generation, especially, is very conservative abroad. They left Nepal with a certain mindset, which has evolved in Nepal but expatriate communities tend to still carry that outdated mindset with them.

But how much has Nepal changed? Does Limbu see Nepal as more open and young Nepalis as more progressive?

“More people might now be okay with the fact that someone they know is gay but they still won’t accept that in their own families,” he says. “They accept that people are gay or queer but they still think its a choice. When I told my father in July 2017, he also thought it was a choice. But I told him, when did you know you liked girls? You just knew and so did I.”

The younger generation might not exactly be as progressive and open as you might expect but at least they’re open, says Limbu.

“They are more aware that there are different people out there,” he says. “They might still use the same words to offend each other but they do understand that a gay man can be quiet and and not just flamboyant or feminine.”

These are small victories, like the kind that he extolled in his friend’s new film. It is, of course, not enough and Limbu isn’t satisfied. That’s why his work goes on, meeting, talking and educating. For Limbu, who started out as a blogger and went on to become a gay icon for Nepal, things are only just beginning.

“At the end of the day, love should happen to everybody,” he says, “and discrimination should happen to nobody."

ON THE MENU

Chimes, Sanepa

Chicken Momo: Rs 340

Fresh Lemon Soda: Rs 110

Paneer and Guacamole: Rs 575

Vesper Chardonnay: Rs 637

19.12°C Kathmandu

19.12°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)